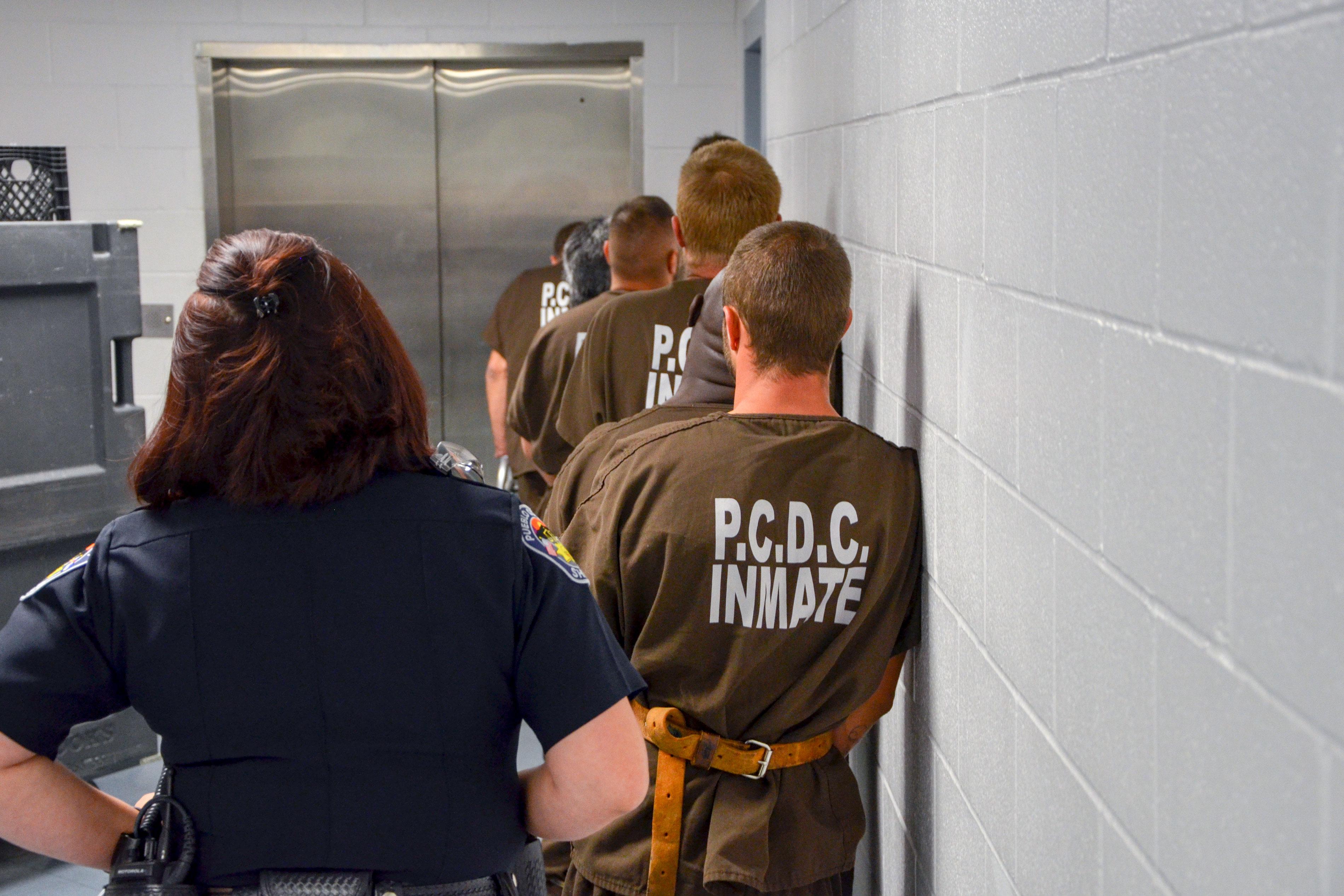

In the last year, judges have either threatened to hold state officials in contempt of court or ordered them to directly move mentally ill inmates to the state’s mental health hospital instead of letting them languish — untreated — in the state’s jails for months at a time.

Colorado’s Department of Human Services has fielded at least 59 contempt of court citations or threats of contempt — including against the state’s chief of the agency — for how long it is taking mentally ill people to access treatment before standing trial, according to an investigation by CPR News.

The numbers underscore a festering crisis across the state’s county jails surrounding people with mental illness facing criminal charges.

“We keep going back to court and saying judge do something, do something, do something,” said Doug Wilson, the state’s lead public defender.

If someone is found mentally incompetent to stand trial, the state is required to “restore” that inmate to competency within 28 days so they can face whatever charges have been filed against them.

But lawyers and advocates say the state is taking far longer and that hundreds of people with a mental illness are left sitting in jail, before they’ve even been convicted of anything, waiting for treatment.

Pat is a mother who lives in the Denver area. Her 20-something son got into a dispute over who was paying for a hamburger in a mountain town in 2017. He was acting strange, according to the police report, and the police called an ambulance. While en route to the hospital, the man punched a paramedic.

CPR isn’t using the family’s name because of concerns that the man’s legal history could hurt his job and life prospects.

The man went to court two months later and was charged with a felony because paramedics are considered peace officers. After he was found mentally incompetent to stand trial, a judge ordered him competency restoration in his community. Pat said she and her son waited for a call from the state on where to go to make this happen — in five months, no one ever called.

When the man went back to court, and the judge discovered he had not had any treatment, he put him in jail to wait for a state mental hospital bed. He sat in a county jail for 55 days waiting for competency restoration.

“I became frantic,” Pat said. “I called the governor’s office. I called our legislative representatives and senators. I called the Office of Behavioral Health. I called the state hospital. I called private psychiatric facilities. He’s got insurance, I called his insurance provider. I called everyone I could think of and no one could do anything.”

After almost two months, state officials moved the man to a jail-based mental health treatment program. Within 16 days, he was deemed competent to assist in his own defense and went back to court, where he pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor. He is now on probation and will see a therapist.

“Total abysmal failure by the state of Colorado,” his mother said.

In addition to the contempt citations filed by private attorneys and public defenders, state officials are also fighting the fourth lawsuit in a decade against the Department of Human Services by Disability Law Colorado.

The latest suit alleges the state is in violation of earlier settlement agreements that guarantee no one waits longer than 28 days in jail for mental health treatment before they go to court.

Lawyers and advocates say that, currently, about 180 people have been waiting longer than that.

“You don’t need to incarcerate someone. You spend $100 a day incarcerating a person. It’s harmful,” said Iris Eytan, a private attorney working on behalf of Disability Law Colorado. “You can’t take back that experience someone had in jail.”

Because of the pending lawsuit in federal court, state officials would not comment on the record for this story. Previously, state officials have said the biggest issue is capacity. The state’s mental health hospital has 449 beds and they are full.

State Sen. Bob Gardner sponsored a bill in the legislature that would have given the state permission to treat mentally ill people in jail for up to five months before they faced charges in a courtroom. The bill died in the final few minutes of the 2018 session because Democratic Sen. Irene Aguilar filibustered to prevent the bill from getting a vote.

“The folks who are suing in federal court are as much in my mind an impediment to a solution as they are getting a solution,” Gardner said. “They would rather see the state of Colorado fined than for us to try and move some things forward.”

A daily fine imposed by a federal judge is a real possibility. At least a half-dozen other states have faced sanctions because of similar problems. In Washington state, for example, officials are paying $50 to $100 a day for every inmate waiting longer than seven days for mental competency restoration.

The problem in Colorado has worsened over the past two decades, in part because of population growth and in part because of a law passed in 2013 that gave people facing misdemeanor charges the right to a public defender. Public defenders often raise the issue of mental health competency in court proceedings.

Since 2000, Colorado has seen a 431 percent increase in evaluating people for mental health competency and a whopping 930 percent increase in the number of people who need to be mentally restored to competency.

Wilson said he doesn’t dispute the growing numbers — he just disagrees with how the state is trying to solve it.

He argues many people are facing minor criminal charges and are of no danger to themselves or the community. These inmates don’t need a hospital bed but would be better suited for outpatient care in their own communities.

“You can’t build enough beds to make this problem go away. It has to be more beds, but also more releases and more restoration in the community if you want to solve this problem,” Wilson said. “They [state officials] don’t seem to want to solve this problem.”

Wilson and Eytan said when mentally ill people sit in jail, they usually get sicker.

“My wish would be low-level, low-risk people be restored in the community,” Wilson said.