Teachers in Pueblo went on strike over pay. If you looked at protest signs during the April statewide teacher’s walkout, many talked about lagging pay and the rising cost of living.

One CPR audience member, Shirl Petrie from Denver, asked if teachers are really that bad off when you compare their pay nationally, and consider their benefits and the summers off deal. We thought we’d take a closer look at it.

What Is The Average Teacher Pay In Colorado?

Data straight from the Colorado Department of Education tells us the statewide average is $52,728 — with a clear spread above and below that mark in salaries. Teachers on the state’s eastern plains are lagging their colleagues in more urban parts of the state. According to the National Education Association, Colorado ranks 31st in the nation with teachers here earning about 15 percent below the national average.

In the lead up to April’s walkouts, a figure bandied about by some was that Colorado was 46th among states for teacher pay. It was an effective rallying cry for the teachers, but the ranking itself came about due to a data error in reporting to the NEA. The proper data would have ranked Colorado as 30th in 2016, not 46th, and 31st in 2017.

Is A National Comparison Between States A Good Indicator About Whether Pay Is Adequate?

Many economists say no, it doesn’t make sense to compare what teachers make in Colorado to Mississippi or New York. Often, salary calculations have baked in differences in cost of living. Instead, economists say a better way is wage competitiveness studies, which compares weekly wages of workers of similar age, gender and level of education.

Bruce Baker, an economist at Rutgers University, says this method also takes into account whether workers in Colorado are willing to work for a little less because of the mountains and lifestyle. Work he conducted for the Rutgers Graduate School of Education/Education Law Center placed Colorado at second to the last in the nation for wage competitiveness, another study he participated in puts it last. Labor economist Sylvia Allegretto has has a separate study with almost identical findings.

“My work shows that Colorado has one of the largest teacher pay gaps in the country,” Allegretto says.

Teachers make about 64 cents on the dollar compared to other comparable, educated workers in Colorado. She says those workers are getting pay raises, but teachers in many school districts are not and that’s fueling teacher shortages and unrest here.

Are Teachers Losing Ground Over Time In Terms Of Pay?

According to federal data, Colorado teachers’ pay in real dollars — that means when adjusted for inflation — has dropped 15 percent since the year 2000. Only Indiana has seen a bigger drop.

As a local control state with no statewide salary schedules, do Colorado teachers’ salaries vary a great deal?

Ninety-five percent of rural teacher salaries in Colorado are below the cost of living. There is a big range from $29, 356 on average in the eastern plains Woodlin R-104 district, to a high average of $75,220 in the Boulder Valley school district.

What About The Benefits Teachers Get?

Teachers do get more generous benefits than some professions – but one research paper shows that even when you factor in benefits, teachers nationwide still earn 11 percent less than comparable workers. Both teacher pay and benefits are declining — as teachers are being asked to pay more for health care and retirement.

One thing often lost in the discussion over benefits is that Colorado teachers don’t get Social Security. Instead, they are covered by the state’s pension, known as the Public Employees’ Retirement Association. Since 2006, school district payments to PERA have roughly doubled from about 10 percent of payroll to 20 percent. The result has been a budget squeeze when the state also was cutting funding due to the Great Recession.

Additionally, if a teacher works a second or third job that does pay into Social Security, they only get back a very small amount because of this federal law.

The average monthly school employee benefit, which includes everyone from superintendents to bus drivers to teachers, is $3,086. For 2016 retirees, the latest year available, the monthly amount drops to $2,303. Some teachers in rural districts have reported benefits are as low as $1,500 dollars a month.

The state legislature just enacted changes to cover an unfunded gap for PERA. Teachers will contribute 10 percent of their salaries to retirement, up from eight percent. Current retirees were promised a cost-of-living-increase of 3.5 percent, but the PERA reform bill lowered the amount to 1.5 percent in two years. Current teachers can still retire with a full pension at 58 but new teachers must now work until 64.

What About Those Summers That Teachers Get Off?

Summers off could be a big attraction that other professions don’t have. But economist Sylvia Allegretto says that still doesn’t explain why teachers are getting paid significantly less for the weeks they are working. She says there has also been a spike over the past ten years in the number of teachers taking lower paying jobs in the summer to make ends meet.

Almost all districts offer to spread a teacher’s pay over 12 months, and some districts offer teachers the choice of either a 9/10 month pay or a 12 month pay, according to the Colorado Association of School Superintendents. But many teachers say with a rising cost of living, they can’t make ends meet.

“Where it used to be a big positive that you had off all summers – in today’s economic environment, they often take second and third jobs over the summer because the money is now much more important than time off so for many teachers, the non-paid time off is actually a negative,” Allegretto says.

Where Does This All Leave Teachers Now?

State lawmakers shaved a little off their $822 million IOU for public schools with the next state budget. And some districts passed local property tax measures, so some teachers will be able to give salary bumps. The teacher’s union says changes to teacher retirement will take money out of teachers pockets and many teachers aren’t happy about that or school funding issues in general.

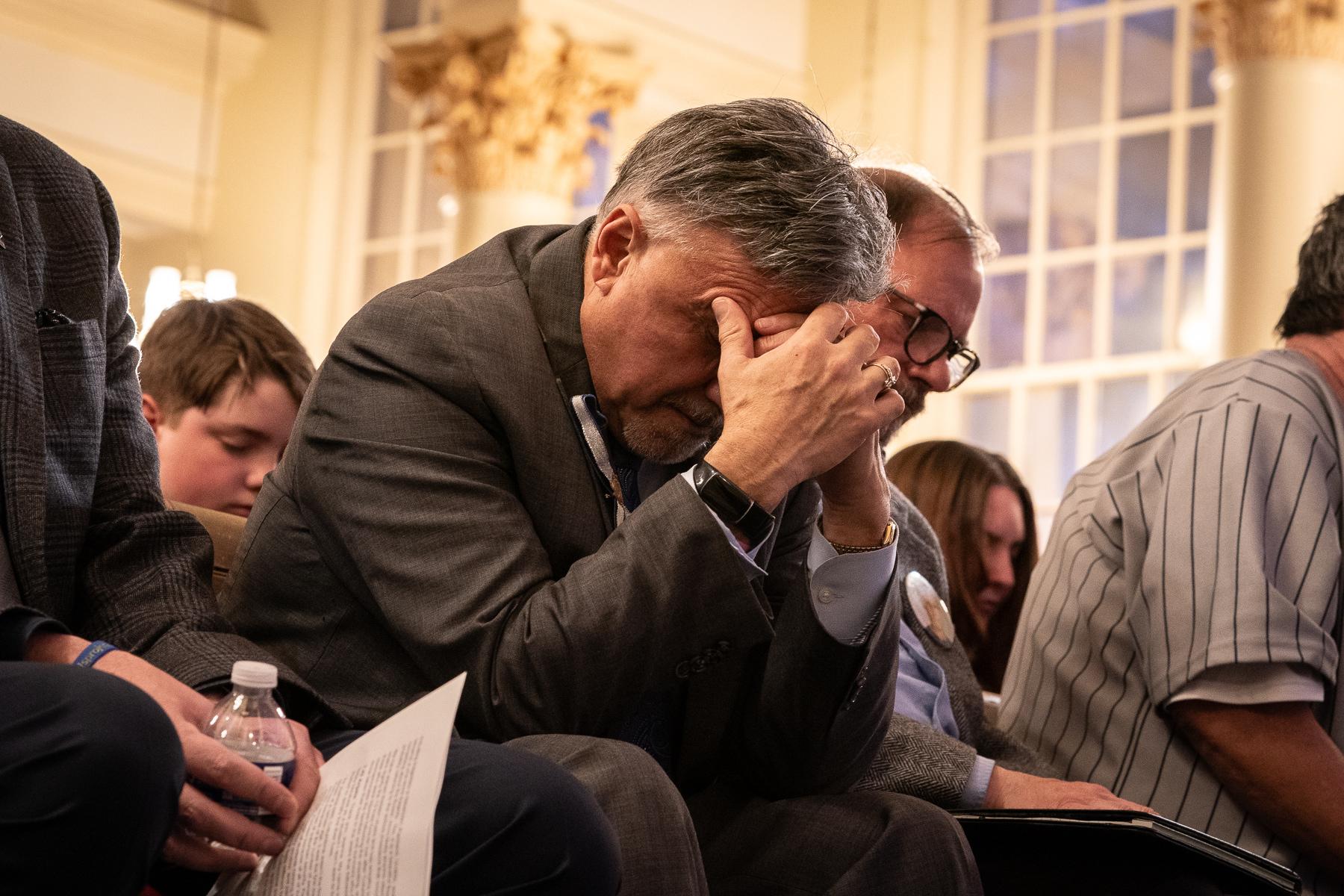

When Pueblo teachers went on strike Monday over pay it raised the specter of more labor unrest on a district by district case. Another path that teachers are focusing their efforts on is a statewide ballot proposal for the November 2018 election to raise school funds.

What Are Your Questions?

There's a lot to talk about when it comes to the way Colorado handles education funding. What do you want to know? You can email reporter Jenny Brundin or tweet us at @NewsCPR or @CPRBrundin. We may contact you for a future story.