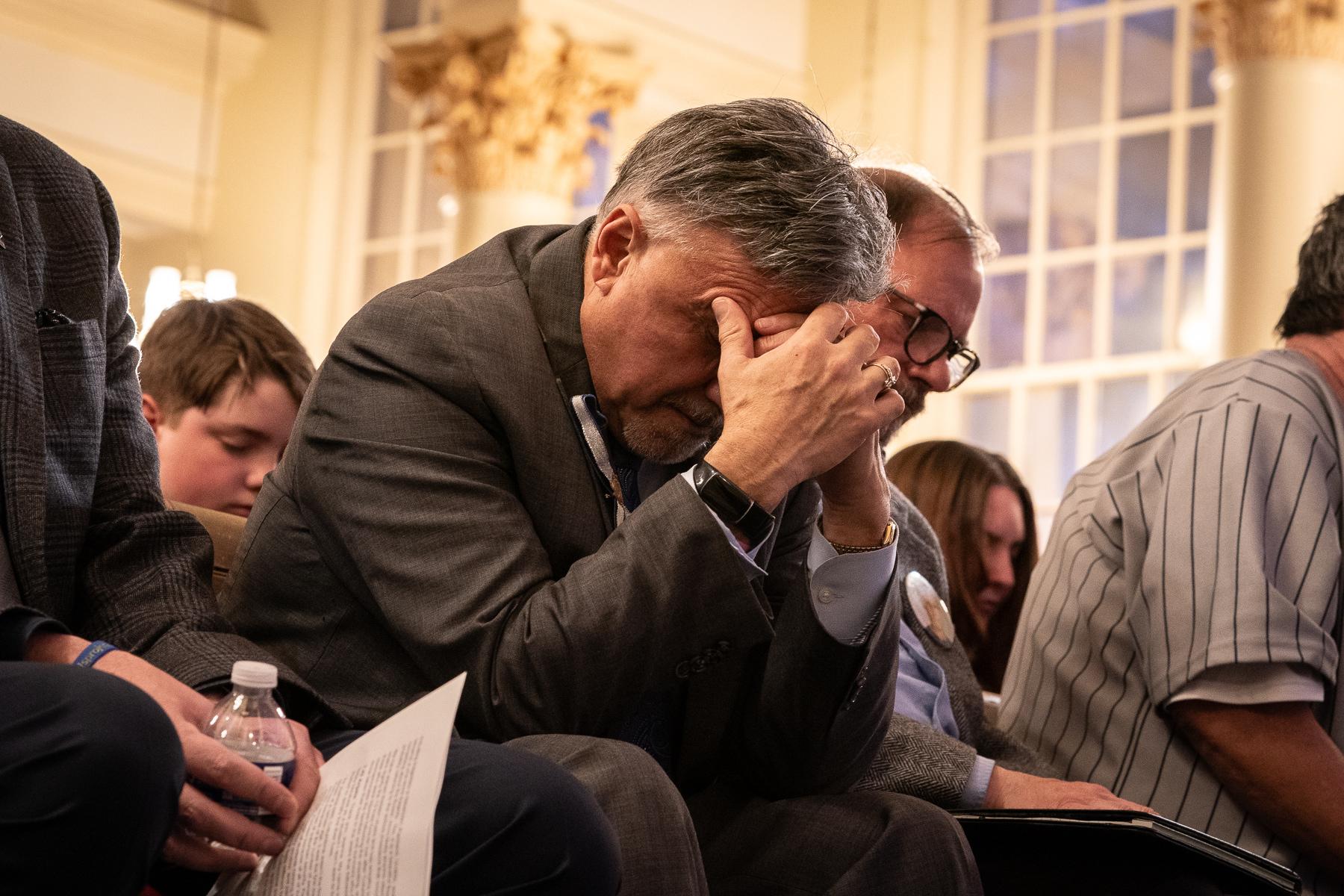

Stories of heartache and loss filled a legislative committee room Wednesday, as lawmakers took up a bill that would give convicts who received lifetime sentences without parole as juveniles a chance at freedom.

The bill would fulfill a lifelong wish of 22-year-old Davena Frazzini of Denver. Her father has been behind bars since he was convicted of murder at the age of 15. Frazzini said through tears that her father “has missed 22 years of birthdays, holidays and celebrations,”

“We have never played on the swings in the park. And we have never had the chance to hold each other in times when we need each other the most,” she said.

But families who lost loved ones to violent crimes also shared their emotional stories of loss. They included Gail Palone of the Eastern Plains town of Bennett. Her son Matthew was 16 when he was shot to death in 1996. She rattled off a rites of passage list that she will never check off.

“No 18th birthday. No high school graduation. No college graduation. No wedding. No children. No grandchildren. That is what we have – nothing from age 16 on,” she said.

The bill passed the Senate Judiciary committee by a bipartisan vote of 3-2 following a hearing that lasted more than four hours.

The bill would allow those who were sentenced to life without parole as juveniles during a particular time period an opportunity to request a hearing to modify their sentences. The legislation would apply to 48 youths who were sentenced to a class 1 felony between July 1, 1990 and July 1, 2006.

An amendment was added to a companion bill later in the evening that would make offenders who were convicted of a sex crime ineligible for resentencing consideration.

During the 1990s, Colorado enacted tough laws aimed at curbing spikes in violent crimes. They included life sentences without parole in cases involving juveniles who received adult convictions of first-degree murder. The state ended those sentences in 2006 after studies on juvenile brain development showed that youths are more prone to making mistakes and taking risks than adults.

“It’s because they’re kids,” said state Sen. Laura Woods, R-Westminster, who is a bill sponsor. “They react and they think about the rewards more than the consequences. They’re risk takers. They don’t think through the long-term consequences of their behaviors.”

In 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down mandatory life sentences without parole for juveniles. And, earlier this year, the court ruled that juveniles who have received those sentences for murder convictions must but allowed the opportunity to argue their release from prison.

“It’s very clear what the Supreme Court decision has done,” said Sen. Cheri Jahn, D-Wheat Ridge, who also sponsored the legislation. “We do have to address that or it’s going to be litigated again and again in court. They [Supreme Court justices] have said sending those juveniles to life without parole is unconstitutional.”

The bill would give judges the opportunity to reexamine potentially mitigating circumstances at a resentencing hearing. Judges could take into account the offender’s age and maturity level at the time of the crime, and whether the offender has a capacity to be rehabilitated. The judge would then be given a range of sentencing options

If a judge finds “extraordinary mitigating circumstances,” the court could restructure an offender’s sentence to between 24 and 48 years in prison. Or a judge can re-impose a life sentence, with parole eligibility after serving 40 years behind bars, according to bill information provided by the Colorado Legislative Council.

The bill received stiff opposition from the Colorado District Attorneys’ Council. Prosecutors argued that violent offenders released early would be an injustice to victims’ families – and a danger to their communities.

Prosecutors brought up the case of Austin Sigg. Sigg was 17 when he kidnapped and killed 10-year-old Jessica Ridgeway in October 2012. Prosecutors expressed concern that the bill could allow Sigg to be released early. However, bill supporters say that Sigg, who is serving multiple sentences, won’t be eligible for parole for at least another 90 years.

The bill must now heads to the Senate floor, where John Michael Leonardelli hopes it will die.

His father, also named John, was stabbed to death in an Aurora parking garage in 1994. He isn’t swayed by the argument that a juvenile life without parole sentence constitutes a cruel and unusual punishment.

“Is not the taking of a human life cruel and unusual punishment?” said Leonardelli. “How can the assailants be given that right when our loved ones who were murdered were never given that consideration?”