It lasted only 30 seconds.

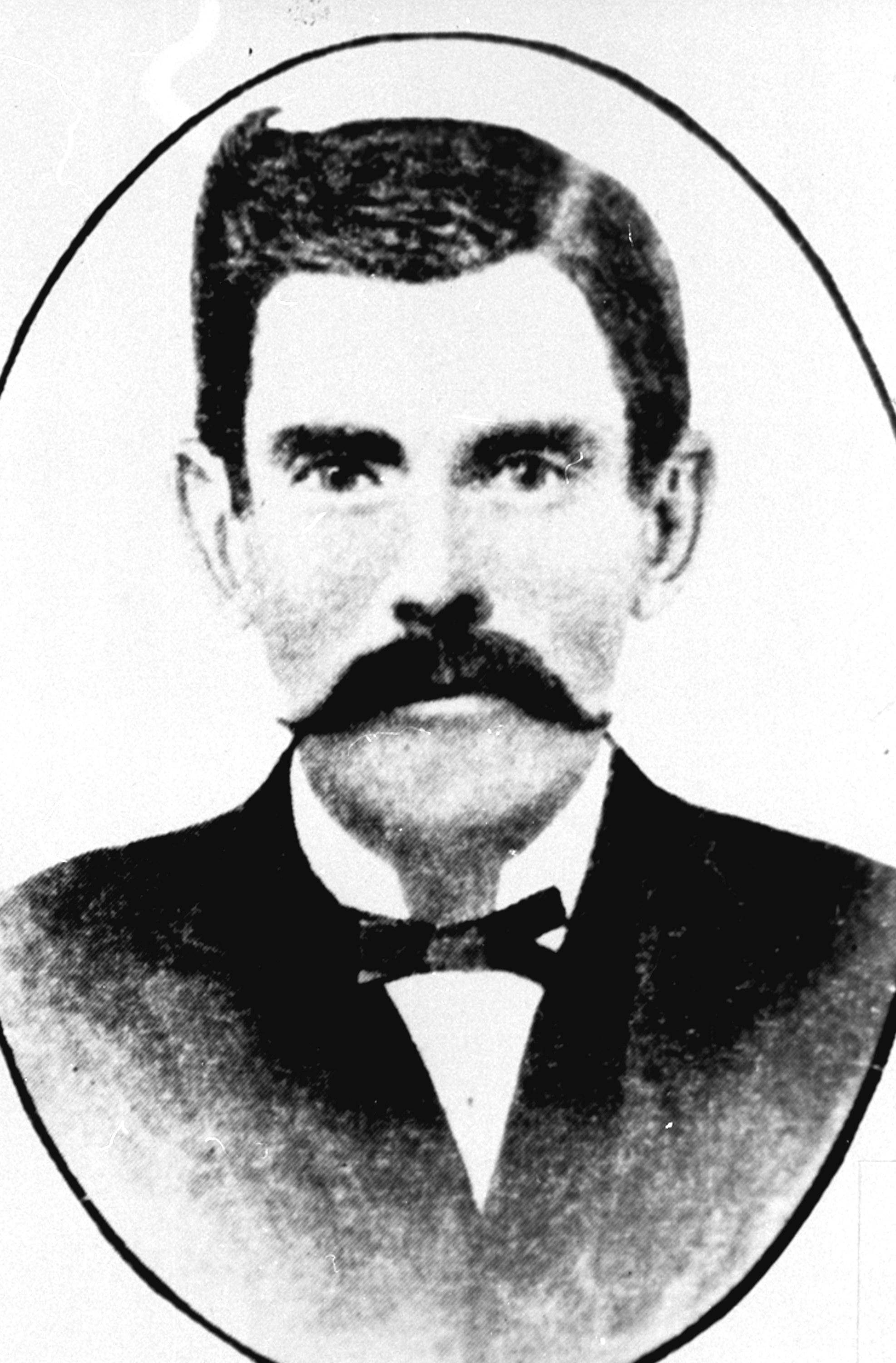

But the gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona, is seared into American memory. After the smoke cleared, lawman Wyatt Earp and his gambling outlaw friend Doc Holliday became mythical figures.

Holliday actually spent a lot more time in Colorado than in Arizona, popping up in Denver, Leadville, Trinidad, Gunnison and other places across the state.

Author Victoria Wilcox spent more than 18 years studying the Georgia-born dentist turned gunslinger. She's considered a Holliday expert. Her novel, published as a trilogy, is called "Southern Son: The Saga of Doc Holliday."

She joined Colorado Matters host Nathan Heffel from Charleston, South Carolina.

Read An Excerpt:

GONE WEST The last thing on his mind was a train robbery. Although he knew about the $100,000 in gold rumored to be aboard, enough to make any outlaw eager, no one had ever robbed a moving train west of the Mississippi before. As long as the Rock Island Line’s passenger train No. 2, bound from Council Bluffs to Des Moines, kept up its dizzying speed of forty-miles an hour, horsed bandits would have a hard time catching up with her. But as the train neared Adair, Iowa, it slowed for a grade and a curve and the engineer hollered out that something was slung across the tracks. He slammed the engine into reverse and the train shuddered and groaned, then jumped the rails. The locomotive thundered down the muddy bank of Turkey Creek spewing smoke and cinders from the chimney and lolling to one side, twisting the couplers and throwing the passenger cars skyward. The ground shook with the impact as steam rose from the troubled creek bed. And waiting alongside the bridge to greet the terrified passengers as they struggled from the wreckage was a white-robed gang of train robbers brandishing pistols and rifles and shouting the Rebel yell… “You gonna buy that paper, Mister, or just stand there readin’ all day?” the newsboy on the Galveston Strand complained as John Henry lost himself in the details of the West’s most daring train robbery. The engineer had been killed, thrown from the locomotive then crushed to death as it Until that summer, the gang had kept their outlawry to holding up banks in the Missouri back country. This enterprise with the railroads was a whole new kind of crime, and newspaper sales soared whenever there was a report on the search for the elusive Jesse James. Aside from the gruesome death of the train’s engineer, it would have been a perfect robbery had the money actually been on board and not delayed until later, leaving the gang only six-thousand in cash and jewelry taken from the express messenger and the passengers. But it was a thrilling attempt, even so, and folks took to the story like a dime novel come to life. Not since the long-ago legends of Robin Hood had there been such a popular outlaw, and ladies openly But to John Henry Holliday, late of Georgia by way of a fast ride across Florida and a sailing ship to Galveston, the story of Jesse James was more of a relief than anything else. For with the newspapers filled with tales of the dashing outlaw, there was little chance that a shooting on a river in South Georgia would be reported. Not that there was all that much to report about such a commonplace crime: a young black man gunned down by a young white man. But it was John Henry’s crime, and though he had run from Lowndes County before the law could catch him, then spent a long night in anguished prayer repenting of his sin and begging for God’s forgiveness, he knew that repentance alone would not satisfy the State of Georgia. If the law decided to come after him, he could still hang for murder. So he anxiously read every newspaper he could get his hands on, searching for any mention of violence on the Withlacoochee River, and was relieved to see the name of Jesse James, not John Henry Holliday, spelled out across the front page. Let the James Gang get the fame; he’d be happy if his own name never made the headlines. There was certainly nothing else about him that would draw attention. He was of average height and average build, although a little on the lean side on account of a bout of pneumonia he’d had while spending two cold winters in dental school in Philadelphia. His coloring was fair, his eyes china blue, or so said the girls back home who’d called him handsome, though mostly it was his cousin Mattie Holliday calling him handsome that had meant something to him. And though there were other, less pleasing, things that Mattie had called him, as well – stubborn, selfish, arrogant – if those had been his only sins, he wouldn’t be in Texas now, reading the paper and watching for any mention of his name or what had happened on the Withlacoochee. But the truth was, he was running from more than just the law. His father had thrown him out of the house and ordered him never to return, the result of a disagreement over his plan to marry his cousin Mattie, though Mattie had already wrecked those plans herself by telling him through her tears that her Catholic faith would not allow first cousins to marry. She loved him but she could not be with him, not ever. And the pain of those two denials, his sweetheart’s love and his father’s affections, had driven him into a drunken stupor and an unthinking shooting that sent him west fleeing for his life. Yet other than a few bad dreams, a haunting worry over the long reach of the law, and a still healing heart, he was in hopeful spirits, having stepped off the ship at Galveston Island sunburned and wind-blown from the sea voyage, and feeling amazingly well. While most of the other passengers had spent their time aboard the tall ship Golden Dream leaning over the rails and vomiting into the turquoise waters of the Gulf of Mexico, the sailing had actually seemed to agree with him. The fresh sea air had cleared his lungs and the prospect of starting a new life in Texas enlivened his mind. And though he had only the vaguest of plans for his immediate future, his long-term goal was set: he would find his way to his Uncle Jonathan McKey’s plantation on the Brazos River and beg Reprinted from Southern Son The Saga of Doc Holliday: Gone West by Victoria Wilcox, with permission of Knox Robinson Publishing, London. Copyright (c) Victoria Wilcox, 2014 |