CHAPTER ONE An Unexpected Page of Life I hope it does go on and on

forever, the little pain,

the little pleasure, the sun

a blood orange in the sky, the sky

parrot blue and the day

unfolding like a bird slowly

spreading its wings, though I know,

saying it, that it won’t.

(Susan Wood, from “Daily Life”)

In the corner of my mind reserved for precious childhood memories is a vision of a book of unbelievable magic. As I open its pages, a small village appears, rising from the two-dimensional into a delightful three-dimensional paper world—the extraordinary, our reality, emerging from the ordinary. In my aging mind I see Brigadoon, rising to reality, destined to disappear once again, speaking to us of the inescapable passing of our life.

We all know that life has margins. Once we are an adult we know that, and we have no choice but to accept that what we have been given is a precious, unexplainable point in time. Here I am, poised at the edge of this eleventh-hour moment, just before life’s inevitable disappearance. Perhaps these are the most precious moments of all, given to us at a time when we are most susceptible to needing a glimpse of the nuances and small wisdoms of being.

By looking within a bit, we may gain a sense of the enchantment of the life we have been given, or what we might call the poetry of our existence. This last chapter, which has seemed so unyielding, such a permanent, unbending force, is probably going to be short, and so we must decide quickly: What shall I do with these months or years? How do I live this miraculous moment in time? How can I see it as magical and vigorous and not as a time of unhappy tears?

Contrary to what our culture teaches, that old age is a sad and dreary time to endure but not enjoy, many oldsters I know would deny that these years denote the absence of all the joyful pages of life. Granted, old age is often a time of added illness, and we probably spend more time at the doctor than we did at thirty-five, but until end-times come, most of us have no trouble laughing and enjoying these gifted years. With a bit of effort on our part, and a show of wisdom, this precious time can be to us a beautiful, rich, meaningful interlude between now and then. It offers a different kind of happiness and fulfillment than we found earlier in our life, but it can be sincerely rewarding, and its tentative quality makes it doubly prized and doubly precious.

That this moment is the only one we know that we have for sure gives it an uncommon quality. I am eighty-five, and I sense that this is such a moment in my life. Please join me as I share this time with you. Rather, let me clarify: I am unable to tell you what aging is like if you haven’t been there, but I want to tell you what I am learning from the experience.

It is not to our benefit, however, that much of Western society sees old people as needing to be shelved, a tagline that chronicles our culture’s way of registering us as useless, expensive, and a difficult obligation. That said, Medicaid costs for seniors are expected to soar. According to Natalie O’Donnell Wood of the Bell Policy Center, Colorado alone “can expect significant growth in age-based Medicaid expenditures—from $1.04 billion in FY 15–16 to just over $2.325 billion in FY 29–30, an increase of more than 100 percent” based on recent projections from the Colorado Futures Center. Wood states that the CFC “lists two reasons for this projection—growing enrollment and growing health care costs for this age cohort.”1 Added to that, according to the US Government Accountability Office, about half of all households aged fifty-five and up have no retirement savings at all.2 Such concerns need to be considered and ideas engendered to deal with these discrepancies, instead of simply cutting benefits for this growing group of Americans. The shelf for the oldsters of 2030 may become very wobbly if we wait till 2029 to consider solutions.

However, recent research tells us that it is possible, and even likely, that our elder years have hidden value and worth for both ourselves and others, even as we gradually begin to lose skills and health. The experts also inform us that we have some control over how rapid this loss will be. Shelved: A Memoir of Aging in America is my attempt to unearth the truth about this time of life.

Should I make the effort to present as complete a human being as possible to my world? Or, rather, fold my tent and prepare for Brigadoon?

I need right here to let you in on a little secret: I honestly like myself better now than I did when I was younger. These years and my experiences have deepened my understanding of myself, my life, and my view of others. And living in our new retirement community (which I like to call “Planet X”—more about that later) has changed some of my attitudes, making me, I think, a more complete person. My secret motivator has always been hope—hope that I will not die until I am happy with the me that I am. I still have some unfinished matters to attend to (which may be obvious to those who know me), and I wish not to leave until I like myself a bit more.

So let me begin my story …

As though coming out of a dream a few years ago at eighty, I woke to find that I had long since opened this unfamiliar page in life’s book called “old age.” I must admit that I hadn’t recognized much slippage before this rather late date, but it kind of makes sense considering the reputation age has among my cohorts. One doesn’t brag about getting older. One doesn’t even admit to it until forced to. Instead, one tries to “think young.” I just hadn’t thought much about being old. I didn’t feel old; I felt good! I was lucky enough to still be able to get around well and participate actively with both young and old friends and keep conveniently busy.

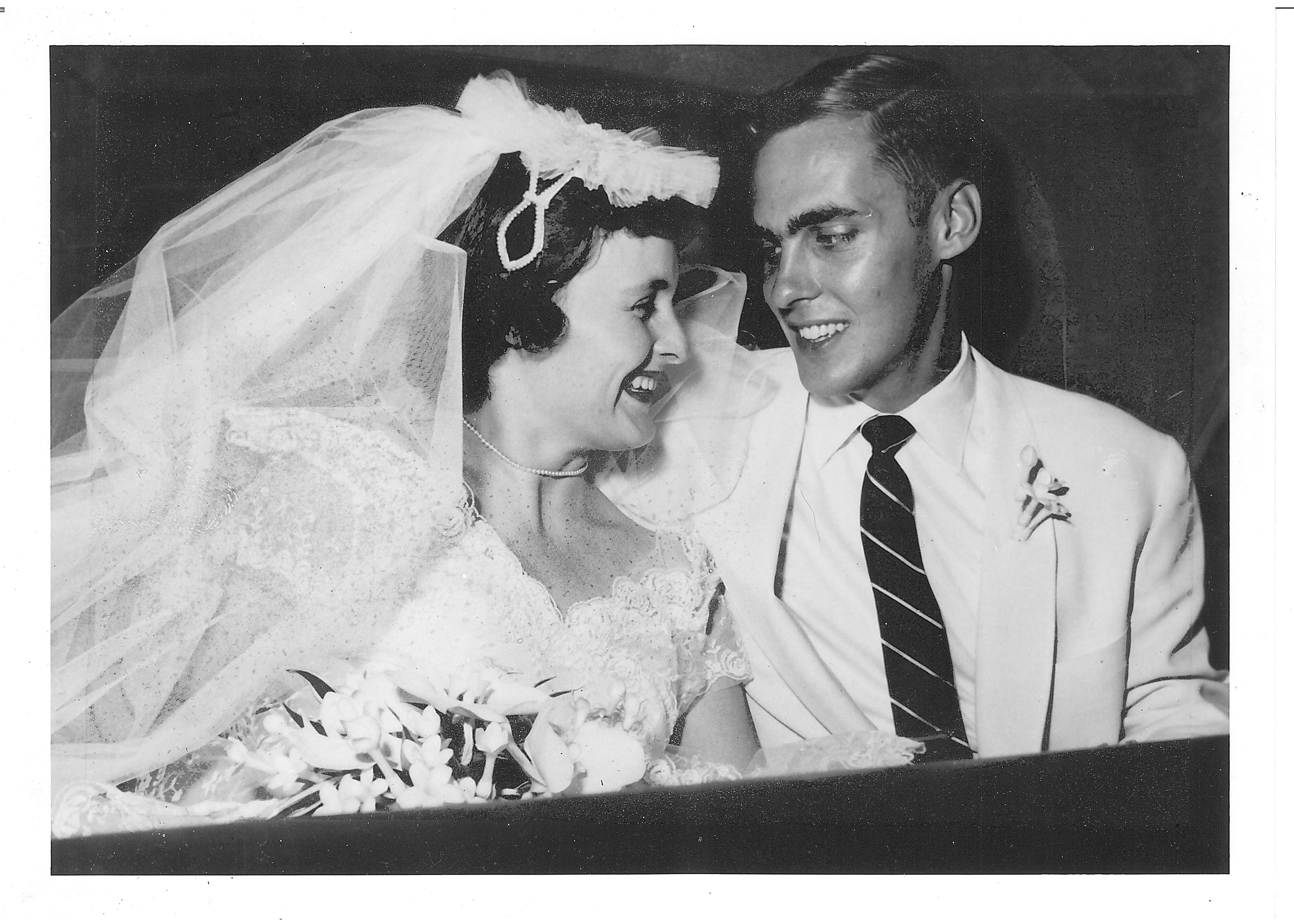

I have since found that it is usually a sudden illness or trauma that wakes one up to the fact that life is gradually ebbing away. But my husband and I had not had any such serious moments and thus had little reason to “think old.” Our time of awareness came when suddenly (or so it seemed) my husband began the descent into dementia, while at the same time developing some serious physical problems.

As a result, I now find myself and Dear Hubby, also eighty-five, in an existent laboratory of the phenomenon we call aging: Planet X, an independent senior living residence in our hometown. The unexpected and, I must say, unplanned had become a reality. What caused us to leave our home? I sometimes questioned myself: should we have stayed there? But in so many ways this has been a good move that neither of us regrets. The friends we’ve made here have become very dear. I so value being able to knock on a door and find a friend. And, when needed, a helper is always at hand.

Reprinted from Shelved:A Memoir Of Aging In America by Sue Matthews Petrovski with permission of Purdue University Press. Copyright (c) 2018 Purdue University Press |

Read an excerpt from "Shelved: A Memoir of Aging"

Read an excerpt from "Shelved: A Memoir of Aging"