Updated 9 a.m. -- Denver teachers are one step closer to a strike.

After 10 hours of negotiations Friday, talks between the teachers union and the city’s school district collapsed without an agreement on a new pay and compensation system and contract for 5,300 teachers.

Members of the Denver Classroom Teachers Association will vote Saturday and Tuesday on whether or not to strike. The earliest a strike could happen is Jan. 28.

“It is very disappointing. We fully committed to negotiations for more than a year with a goal of keeping more of our talented and dedicated teachers in the district,” said DCTA President Henry Roman.

At 10:30 p.m. DCTA bargaining team member Rob Gould told teachers he’d talk to them Saturday, effectively ending the negotiations. The contract expired at midnight.

Superintendent Susana Cordova said she was disappointed the negotiations ended early.

“We were very willing to continue to keep working,” she said. “It's really important for the students of Denver, for our families, for our community that we work as hard as we can, and given that we still have time, I think it's unfortunate that we are where we are.”

Cordova said she wants to make sure teachers have good information about the district’s most recent proposal so they can make an informed vote. She said the district’s proposal gives teachers an average pay increase of 10 percent between this year and next. That includes previously agreed upon cost of living increases.

“I'm not sure that we have seen anywhere across the nation teachers who have gone on strike to reject a 10 percent increase,” she said.

Cordova, who has been on the job for less than two weeks, inherited the dispute from her predecessor Tom Boasberg. Negotiations began more than a year ago.

$8 Million Gap

In the end, the two sides were more than $8 million apart in their proposals.

The crux of the negotiations centered on how much money should go into base salaries versus incentives. Denver teachers wanted more money in their base salaries, instead of receiving incentives for things like working in a high-poverty school or in a school with high ratings. Teachers say those situations are unpredictable, and can leave them earning less than they did five years ago.

The DCTA’s proposal didn’t include a high priority schools incentive, which union officials said amounted to $5 million. The $2,500 incentive applies to teachers at 30 schools.

Union officials and some teachers believe the money is better spent on base salaries.

One of them is Jess Schneider, who said that during her three years at Noel Community Arts School the incentives were not retaining teachers.

“Every year we are hiring, five, six, seven sometimes upwards of 10 positions in our already very small staff,” she said.

But Cordova said district research shows those incentives work.

“I was a principal of one of our highest priority schools and the ability to recruit people is significantly harder and the ability to keep teachers is significantly harder in our highest poverty schools,” she said. “We've seen increases in retention with the use of these incentives.”

Teachers also wanted their salaries to increase more frequently over time, as is the case in other districts with traditional “steps and lanes” salary schedules.

Denver Public Schools negotiators agreed that base pay needed to rise and incentives needed to be streamlined so teachers could have predictability. But district officials also said they need to remain faithful to the objectives of the incentive system passed by Denver voters in 2005.

That’s meant that while the district has redirected millions of dollars from incentives to base pay, the district said there wasn’t money to meet the union’s salary schedule demands totaling about $30 million.

Teachers receive raises on their salaries based on their number of years of experience and education level. The district has proposed additional ways to get a salary bump, such as getting a raise when you’ve been with the district 10 years. The district also added a salary bump for a master’s degree plus 30 credits of continuing education, and a bachelor’s plus 20.

In the district’s proposal, teachers would get a “lane change” — or salary bump — for an advanced license or certification, such as a national board certification or being qualified to teach college-level classes. At the very top end, a teacher with a doctorate degree and 20 years of positive evaluations could make a maximum of $100,000 -- a status possible for about 200 teachers.

The district’s package increases the amount of money going into teacher compensation by more than $20 million, in contrast to the union’s $28 million proposal.

Progress was made on streamlining incentives and making them fixed. Both sides at one point had tentatively agreed to a $2,500 bonus for teaching in a hard-to-serve position, like a math or special education teacher, and $2,500 for high priority schools.

To pay for the plan, the district proposed $7 million in cuts to central administration. They were also counting on $10 million in new money from Gov. Jared Polis’s budget proposal.

Teachers like to sing. pic.twitter.com/VTONPErtep

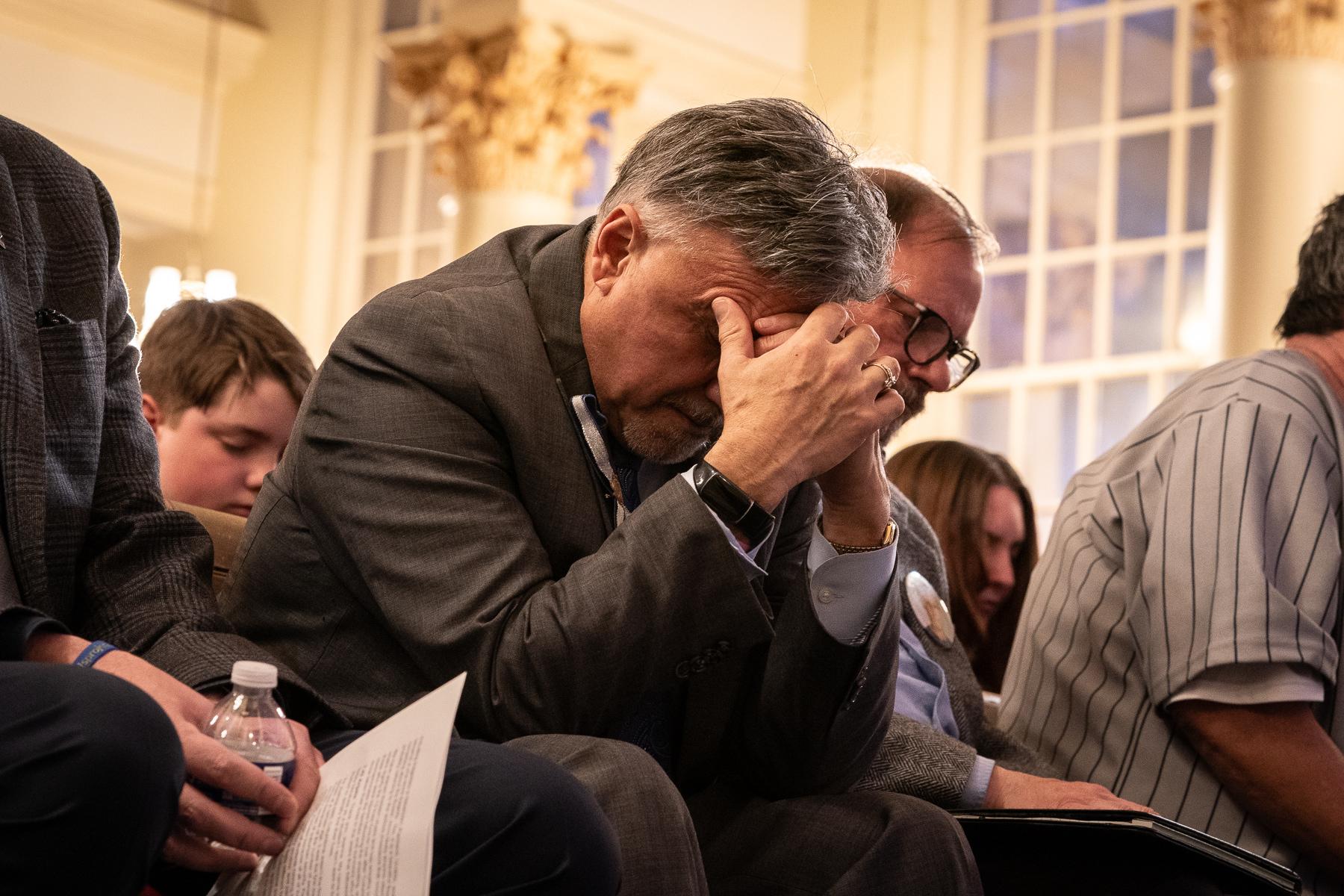

As negotiators caucused in private rooms, the public bargaining room was filled with red-shirted teachers who sporadically clapped and chanted throughout the night. When talks ended, the mood was somber.

“This is not the outcome I would have hoped for,” said Hamilton Middle School teacher Joel Mollman. “It's the outcome that we need to get what Denver teachers deserve.”

Eagleton Elementary school teacher Ashley Nance, 32, says she will vote to strike. She has been teaching for four years. She can still only afford an apartment with a roommate. Her salary is about $47,000 a year, but she gets bonuses on top of that because she’s in a hard to fill position and a high poverty school.

While those incentives help, they don’t address the real issue of working at struggling schools.

“The workload where we're working an average of 60 hours a week, you see teachers leaving at 9 p.m. with you on a lot of nights, and we're getting paid for 40-hour work weeks. What's hard about that is knowing that that's probably not a sustainable workload,” she said.

But if Nance transferred to a school that wasn’t high poverty and struggling — and not as taxing on her — she would lose those incentives and could no longer afford to live in Denver.

Nance also has a master’s degree in educational psychology that has left her with $41,000 in loans. “And what's hard is with the district's pay, you get stuck once you have a master's degree,” Nance said. “The only way to move forward is with additional courses, which at this point I simply cannot afford to take.”

Jennifer Horvath is a school nurse, a position also affected by the pay contact. She's in her fifth year, but said makes less than when she started.

“I want to be paid in a fair way, in a way that's transparent that I understand what my paycheck looks like,” Horvath said.

Superintendent Cordova said if the teachers vote to strike, the district will ask the state Department of Labor to intervene.

“We think it's really critical that the state intervenes because we have worked very hard in very good faith with lots of movement,” she said.