In June, 56-year-old Kevin Monteiro was released from prison, where he'd been since the 1980s. CPR’s Andrea Dukakis has been reporting on parole through the eyes of Monteiro and some of the people who've worked with him. This is the third installment of a five part series.

It was October when Kevin Monteiro moved into an apartment in Aurora. It was the first home he'd had in decades. The apartment is on a gritty neighborhood block with a few small stores; it’s just blocks away from where Monteiro says he got caught up in a drug deal gone bad back in the 1980s. He was subsequently convicted of second degree murder for his part in a stabbing.

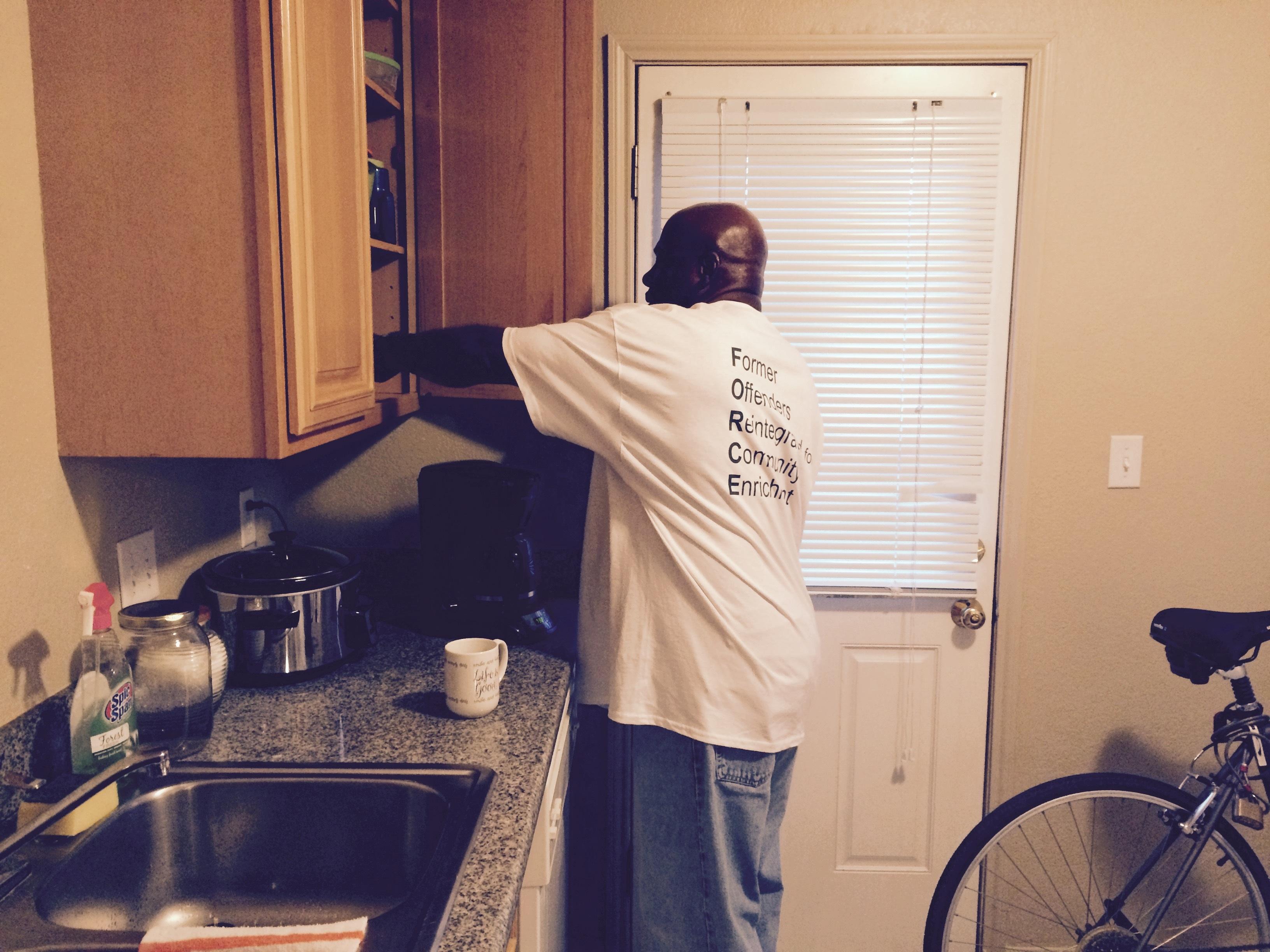

Monteiro's apartment is pretty sparse, but it's neat and freshly painted. Some pictures sit on the floor, waiting to be hung, and a basket of freshly laundered clothes sits on a neatly made bed. He uses his second bedroom as his prayer room -- he’d converted to Islam in prison.

More from this series:

- After decades in prison, first day outside a shock for Colorado parolee

- For Colorado parolee, life after decades of prison begins with survival

- Colorado parole officers balance oversight, encouragement

- Colorado prison chief addresses serious challenges facing parolees

As modest as it is, the apartment is a huge step up from the Aurora hotel where Monteiro was placed temporarily by the state's parole division. After a few days there, he was covered with bed bug bites. Eventually, the imam at a Denver mosque invited him to stay there and sleep on the floor near the main sanctuary.

The problem of work

Monteiro turned to the St. Francis Center in Denver for help finding a job; the organization helps the unemployed find work. His first job, slaughtering sheep, paid little. Eventually, Monteiro found a more lucrative job directing traffic at construction sites at a company that employs several former inmates. He’s fortunate to have secured his $15-an-hour position.

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, men with criminal records are having particular trouble finding work, according to a recent New York Times/CBS News/Kaiser Family Foundation poll. That survey found that those men account for about 34 percent of all non-working males ages 25 to 54.

“I’m proud of myself because I want to get up and go to work --whether I was washing dishes or digging a ditch or directing traffic or whatever it may be, I feel good now,” Monteiro says.

Meager confidence

Monteiro had hoped to move into the apartment sooner but he said, there were things holding him back.

“I was kind of afraid,” he says. He feared making a budget, paying the rent.

But those concrete things weren’t his only fears.

“And I’m just really afraid of failure,” he admits. “You know. I’ve had so much of it in my life. But I’m not afraid to stumble.”

It’s common for parolees--even ones with good intentions--to stumble. A lot of them don’t have a place to stay when they get out. Some have anger issues, schizophrenia, or depression, but don’t have access to their medications when they’re first released.

And most are poor. The prison gives them $100 when they’re released, but that doesn’t go far. It has to stretch out over rent, groceries, utilities, a cell phone, transportation -- and the drug and alcohol testing required by their parole.

Monteiro now keep a strict budget. Out of the $1900 he makes each month, he pays $800 in rent, and most of the rest goes to pay his expenses. But he manages to save a little for himself.

“I have this thing every week, when I get my check, for whatever amount it is, I go get a Starbucks coffee,” he says. “That’s my coffee; it’s what I worked for, you know.”

Following the rules

Monteiro still sees his parole officer every few weeks. On a recent winter day, the downtown parole office is chaotic -- a far cry from the peaceful order of Monteiro’s new apartment.

Dozens of men wait in a large, run-down waiting room. A lot of them look pretty down and out. And just like it was for 30 years -- all of sudden Monteiro is a number again.

He steps to a counter. “I’m here to see, uh -- 52081,” he says, identifying himself.

He’s here to see parole officer Eric Brunner, who’s handling Monteiro’s case these days. Brunner specializes in guys who have been in prison for decades. He asks Monteiro how things are going.

“They’re going really well,” he says. “I’m working. Taking care of my business, just staying out of trouble.”

Monteiro’s worried though. Not long ago, he missed his 10:30 p.m. curfew -- his bus had a mishap so he hopped into a cab to make it home more quickly. Brunner lets it go. But he could have come down hard on Monteiro. These days, a lot of parolees get sent back to prison for parole violations like missing curfew or parole appointments. That’s in part because, two years ago, a parolee murdered Tom Clements, Colorado’s prison chief. Since then, parole officers have been tougher on their clients. And in some cases, for good reason. Some parolees are dangerous.

Monteiro, though, is determined to live by the rules.

It pays off

About a month after Monteiro’s visit to the parole office, Eric Brunner visits Monteiro at his apartment. But not because Monteiro’s in trouble; rather, because Monteiro’s reached a milestone.

It's time to get his ankle monitor taken off.

Brunner uses scissors to cut it off, gathers the electronic equipment that goes with the ankle monitor, congratulates Monteiro and leaves.

Monteiro’s satisfied, but matter-of-fact. These days, he says, it’s the little things that make him happy. Like having a few guys over to watch football.

“I cooked for them,” he says, his bass voice rich, articulate. “I cooked some lamb and rice and they ate some ice cream. We watched the game.” He pauses. “To be able to have food and feed somebody and to be able to have a place where somebody could come and take off their shoes and relax at my place -- that’s a long way, in five months.”

And there’s more. Monteiro has four children spread across the country. He’s slowly reconnecting with them. It’s hard. He understands that he’s been gone for decades.

Right after the holidays, he says, he flew back to the East Coast to surprise his mother. She’d never come to Colorado to visit him in prison so he hadn’t seen her in years.

“When I got there -- Providence, Rhode Island -- my brother picked me up at the airport,” he says, easing into his story. “I said, `Where’s Ma?’ And he said, ‘She’s at home.’

“I said, ‘She don’t know?’ He said, ‘Nah.’ We had planned this whole thing,” he says, smiling.

He and his brother picked up some seafood for dinner and went to her apartment. His brother went in first.

“He waited a few minutes and then said, ‘Ma, it would be real nice if Kevin was here. You know, he loves crabs.’ And my mom, all she said was, ‘My Kevin, I sure wish I could see him again.’ And I said, ‘Well, just turn around.”

Monteiro’s voice quakes as he recalls the rest of the story. He says his mother started crying and he hugged her.

But that visit -- the first in about three decades -- would be his last.

Not long after he returned to Colorado, Monteiro got a call from Rhode Island. His mother had died. He felt blindsided. And a bit lost again, like he couldn’t get a break.

But Monteiro keeps trying. Keeps putting one foot in front of the other. And reminding himself of how far he’s come in these last few months.