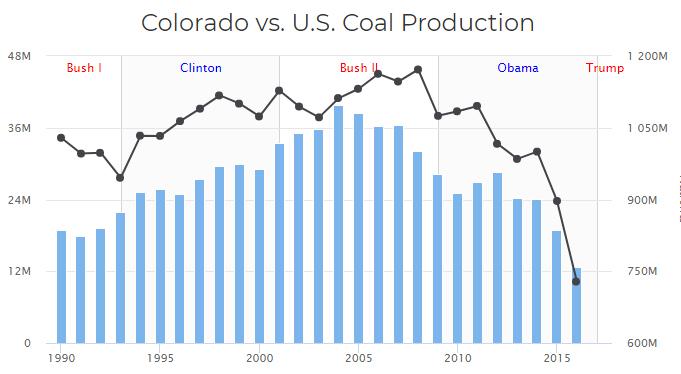

There's been a recent uptick in coal production and jobs, but across the U.S. and Colorado, coal demand, production and employment have experienced steady declines since the Reagan administration. Still, citing President Trump, Stan Dempsey, head of the Colorado Mining Association, recently declared the so-called “War On Coal” to be over.

"When you look at the actions of both the Trump administration and Congress, they very quickly took action to either repeal or not go forward with certain regulatory actions in particular that were intended, in our minds, to slowly or more quickly shut down the coal industry and the use of coal as a source of electricity throughout the country and in Colorado," he told Colorado Matters.

"In particular Congress took action using its authority under the Congressional Review Act to repeal a regulation adopted very late in the Obama administration called the Stream Protection Rule, which was originally intended to address mountain top removal to access coal reserves in Appalachia, but it had huge effects on underground mines using long wall operations," Dempsey said. "That rule could have shut down underground coal mining in Colorado unintentionally."

Projections from most economists do not predict a bright future for coal in the long term; other energy sources are a threat. Natural gas is cheaper and cleaner, and the fracking booms show no signs of slowing down.

But "you cannot forget, or you can't underestimate, the impact regulation has had," Dempsey insisted. "I certainly acknowledge the fracking boom, but let's remember, the fracking boom has really benefited Colorado in seeing a double of oil production, whereas natural gas drilling on the Western Slope where it's more expensive has really not grown very much because of the cost of developing that resource. Certainly, you know, I think that will there be an expansion of the use of coal. You know, it's the utilities who are making the decisions about the choice of fuels."

Read The Full Transcript

Ryan Warner: This is Colorado Matters from CPR News, I'm Ryan Warner. The current White House has a very different outlook on America's energy portfolio from the last administration. Climate change drove a lot of the decisions under President Obama. Under President Trump, coal is sacrosanct. So, what has that 180 degree turn meant in Colorado? Tomorrow we'll get the view on renewables, today it's coal. Stan Dempsey is head of the Colorado Mining Association and he recently declared that the "War on Coal" is over. Welcome to the program. Stan Dempsey: Thank you Ryan. RW: Coal mining saw an increase in production last year, both nationwide and in Colorado. That is bucking, what had been a trend of declines. There had been a lot of factors working against coal the last few years. Competition from cheaper natural gas, even renewables, and environmental regulations. In Colorado a 2010 law mandated the closure of some coal fired power plants and incentivizes other forms of power. What leads you to say the war on coal is over? SD: Well I think that when you look at the actions of both the Trump administration and Congress, they very quickly took action to either repeal or not go forward with certain regulatory actions in particular that were intended, in our minds, to slowly or more quickly shut down the coal industry and the use of coal as a source of electricity throughout the country and in Colorado. RW: I imagine you might point to the clean power plant that had its tentacles with the Paris Climate Agreement. What else is on your mind when you think of that regulation? SD: Well in particular Congress took action using its authority under the Congressional Review Act to repeal a regulation adopted very late in the Obama Administration called the Stream Protection Rule, which was originally intended to address mountain top removal to access coal reserves in Appalachia, but it had huge effects on underground mines using long wall operations. RW: These are various types of coal mining. SD: Exactly, underground mining where you have a device that uses, it's a long, basically saw, that goes out and accesses the coal underground very efficiently. That type of mining though, has some impact, but potentially on intermittent streams and streams above ground. That rule could have shut down underground coal mining in Colorado unintentionally. RW: The Stream Protection Rule required mining companies to return nearby water ways to their original condition after mining in the area was finished. The aim was the clean up heavy metals like arsenic, mercury. Some context, I think this is important, there are currently six operating coal mines in this state. Employing just over 1,100 full-time workers, that's an estate with a labor force of 3 million. And while production was up last year, the number of coal jobs in Colorado was flat here and it actually dropped nationwide by about 7%. What do you make of those employment numbers? SD: I don't think anybody should be surprised that with fewer mines that we have fewer employees. But I think what is also something that's occurred is technology and the application of technology making mining more efficient, making mining more safe. RW: There's more automation in mining? SD: Absolutely. RW: Okay. Do you expect there to be any increase in coal jobs in Colorado or is flat in your mind, and holding, the right direction? SD: I certainly think at the beginning pleased there haven't been fewer, that there have been fewer job losses. I think that there has been more additional contract miners as mines have picked up some production, particular mines, and we would hope that those numbers would grow, particularly when there's more certainty, and I think there is more certainty in the fate of the existing minds right now. RW: There are policy changes for sure, but what difference does it make sort of psychologically to have a president who's so bullish on coal? I mean, when you look at coal jobs overall, the figure of the miner under this administration has become almost a mythic symbol of the working class the president wants to revive. What kind of boost does that give an industry? SD: Really have a couple of answers, and one is a reflection of perhaps a lot of voters, particularly in the Midwest, or Pennsylvania, Ohio, that the president seemed to attract the attention of when he was running for office, that there was a feeling in America that working people were being ignored, or that the jobs that they had, or were hoping to have, were fading away, and that the president was able to tell a story and give people some hope that those jobs could be revived. And they wouldn't be attacked, I mean, their employers wouldn't be under attack through regulatory fiat, for example. I think the president was able to capture that theme. This election, it surprised me as I came into this job just prior to the election. I'd never heard of people saying the fate of our industry depends on who wins the White House, but the contrasts were stark. Secretary Clinton said, "I'm intending to put a lot of coal miners out of their jobs." I mean, she may have been misquoted, or maybe that's taken out of context, versus, as you said, such a strong position that President Trump took on coal. RW: You're listening to Colorado Matters. I'm Ryan Warner, and we are assessing what the Trump administration means for energy in Colorado and across the country. Tomorrow we'll get the view on renewables, today it's coal with Stan Dempsey, head of the Colorado Mining Association. We have largely focused on regulation and attitudes towards coal, but, you know, we should say that projections from most economists don't look great for coal in the long term, that other energy sources are really the threat here. The natural gas boom is the elephant in the room, to some extent. It's cheaper, it's cleaner, and this fracking booms shows no signs of slowing down. Do you give too much credit to regulation when it's really market forces at play here? SD: Well, you cannot forget, or you can't underestimate the impact regulation has had. I certainly acknowledge the fracking boom, but let's remember, the fracking boom has really benefited Colorado in seeing a double of oil production, whereas natural gas drilling on the Western Slope where it's more expensive has really not grown very much because of the cost of developing that resource. Certainly, you know, I think that will there be an expansion of the use of coal? You know, it's the utilities who are making the decisions about the choice of fuels. RW: Driven in part by policy. SD: Oh, I think [crosstalk]. RW: [crosstalk] in Colorado voters themselves- SD: Exactly. RW: ... Passing a renewable energy standard way back in 2004, which has only grown since, said, "We SD: Well, I think the voters said they wanted more renewables. I don't think they said less coal. You can RW: I don't think it's a huge leap to say that that's a swap that they might like to make. SD: But remember, the renewable industry was nowhere the size in 2004 that it is now, and that was driven by, you know, the wind industry, when people say wind is now competitive with coal, well, you've got a production tax credit that has really propelled the economics of wind, and I think Warren Buffett said it well. He wouldn't be investing in mid-America energy ventures if it hadn't been for the tax credit. So tax policy, regulatory policy, and Colorado's a leader in setting a lot of those policies. RW: And what does that mean for the future of coal in Colorado? I mean, when you look at the policies that voters have set, through the initiative, and then subsequent governors have set, to convert coal-fired power plants to natural gas plants, for instance, to boost solar and wind. Is this a friendly state to coal or an unfriendly one? SD: I think the state is still friendly to coal. I think people recognize coal's contribution to local economies. I think that the existing mines now all have pretty much a defined marketplace for their coal. The one mine that is having increases is finding new markets of short-term contracts, and they're finding markets both internationally and throughout the United States. RW: Yeah, I think it's important to point out that a lot of the market for Colorado coal is not in SD: Right. RW: Much of it is abroad. Is that right? SD: I think in the 2016 report, we had half the coal went outside of Colorado, but many of the mines we have, have dedicated markets. The Northwest Colorado Mines generally support the Crag and Hayden stations. The mine in Durango supports the cement plant. RW: Of course coal is a commodity, so similar to oil, it follows the ups and downs of those very broad international markets. Meanwhile, renewable energy is following a cost curve. It's really more akin to technology, where it's getting cheaper and cheaper all the time. How much do you see renewables as an existential threat? Or just part of the portfolio? SD: I think that's the decision, in terms of seeing it as a threat, I think the people who have our fate and the electric consumers' fate in their hands are both elected officials, regulatory officials and the folks who own the investor run utilities, who are making decisions about their fuel choices. RW: And Excel is increasingly, for instance, getting more of its power from renewables. SD: They are, and they certainly have the Colorado Energy Plan. And I think their reasoning for, that's the effort to convert two units in Pueblo, at the Comanche facility. They're wanting to adopt that as quick as possible, so that they can take advantage of the production tax credit. RW: Stan Dempsey, it seems to me that part of the future of coal, certainly if laws regulating greenhouse gas emissions eventually get more strict, is in so-called clean coal, the idea of creating clean coal technology. My understanding is that's incredibly expensive, the technology has a long way to go. How much is the industry focused on that, as its future? SD: I think the industry is focused on it. States like Wyoming, and even Colorado, are partnering with companies. I know Tri-State has a project that they're working on up in Wyoming, in partnership with the state and other partners, to try to develop some carbon capture and sequestration activities. So I think, the question is, is it the mines who are doing the partnering or is it the utility operators themselves? RW: At which end? SD: Yeah. RW: How much do you think about climate change? SD: We think about it quite a bit. And as an association, we look at all kinds of pieces of legislation, and decide if we're going to be active or take positions on those things. RW: I guess what I mean is, how much do you think of it as an existential threat? Speaking of the second existential threat. SD: You know, I think it's a question of how our members are looking at it. And our members have different views on that, and it's kind of played itself out. You know, in the hard-rock mining side, we had companies that did not want the Trump administration to pull out of the Paris Accord. I have coal companies who are continuing to have, they're thinking it's evolving on climate change. And there are some companies back in the East that are pretty hostile to the issue. So we're following the lead of our members. RW: And it varies among them. Thank you for being with us. SD: Absolutely. RW: Stan Dempsey, President of the Colorado Mining Association. We talked about how coal fares under the Trump Administration. Again, tomorrow a view on renewables. This is Colorado Matters from CPR News. |