Sunglasses. That’s the first thing that stands out in a photo shared with us by Julie North after we asked for your favorite pieces of public art in Colorado.

The entire mural features 12 gigantic faces, each wearing a pair of shades.

“What is being reflected in their sunglasses is the history of the Denver metro,” North says. “So you see, in one pair of glasses, teepees. And then in another you see the city skyline. And it’s just cool.”

The mural, which covers two long walls underneath Speer Boulevard along Little Raven Street, is called “Confluent People.” We reached out to the artist, Emanuel Martinez, to learn more about the artwork and its subject matter that spans many generations.

1) The Meaning Of The Mural’s Title

The name “Confluent People” nods to nearby Confluence Park, where the South Platte River meets Cherry Creek. This spot has played a significant role in Denver, long ago attracting Native Americans and settlers searching for gold. Today it’s surrounded by the kind of rapid development that now defines Denver.

The mural depicts the various types of people and animals that have lived in the Mile High City over time. It’s that spirit of coming together that Martinez has worked to capture.

“We all share a presence in this country and ought to maintain some harmony and equality,” he says.

2) For Emanuel Martinez, This Wasn’t A Solo Work

One of the first things the artist will tell you about this mural is that he didn’t do it alone. Fifty students from different high schools helped him finish it in 2000.

“The collaborative aspect is the most significant because it engages young people,” Martinez says.

The artist sees himself in a lot of these young people. He still creates murals around the country. As part of a nonprofit called The Emanuel Project, the artist paints with incarcerated youth -- like his own mentor did for him many years ago.

3) Art Helped Martinez Leave Behind A Troubled Youth

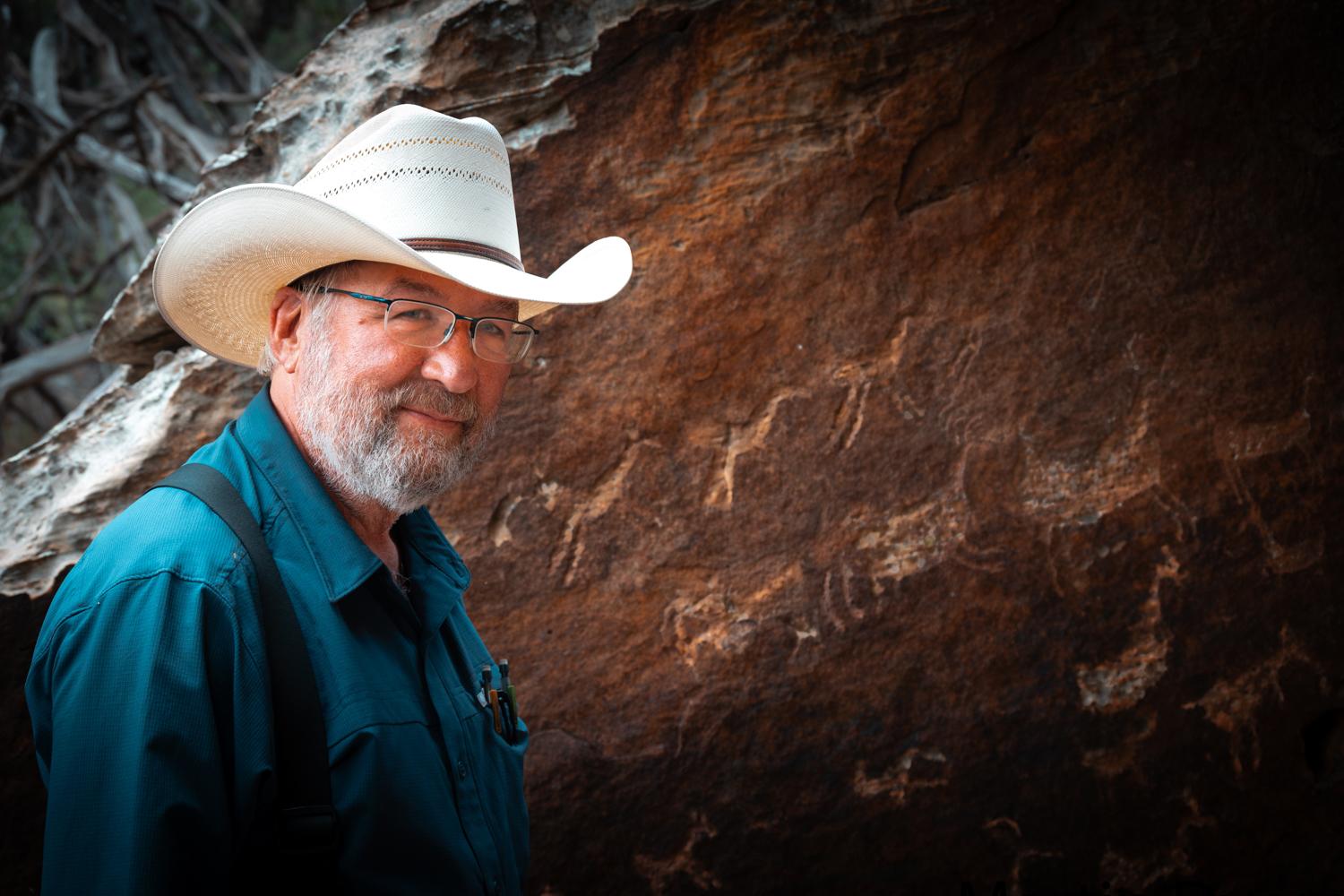

Born in 1947, Emanuel Martinez was one of 12 kids from a poor family raised in Denver’s Five Points neighborhood.

At 13, Martinez was caught joyriding with a friend who stole a car. He ended up in a juvenile detention center, a place he would be in and out of for a couple of years. That’s where Martinez says he discovered his talent.

“I essentially started drawing with matchsticks and paper towels because they wouldn’t allow us paper and pencil for the first few weeks I was there,” he says.

He went from these simple drawings to a mural with cartoon figures painted inside a rec room. It served as a declaration. Martinez knew he wanted to be an artist.

“It just inevitably put me on the right track and get (sic) me out of trouble,” he says. “It was also something I could share with other people to try to make their lives better.”

4) Martinez Participated In Colorado’s Chicano Movement

An artist named Bill Longley was on the lookout for at-risk youth with artistic talent, and Martinez caught his eye. Longley made Martinez, then 15-years-old, a deal: He’d get him out of jail and into school if Martinez agreed to be his apprentice for two years.

Martinez said yes.

Longley later pushed him to get involved in the Chicano Civil Rights Movement. So Martinez brought his creativity to the cause while he worked alongside activists like Corky Gonzalez. The artist painted inside the Crusade for Justice building, but eventually he hit a roadblock.

“There was no place here in Denver or in the country that I could find where I could really learn anything about mural painting,” Martinez says.

So Martinez hitchhiked to Mexico -- where artists like Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros earned international acclaim for their large scale works.

“I was very inspired by their movement and how they were able to help educate the masses through mural painting,” he says.

Martinez returned to Denver in 1968 to pioneer contemporary chicano murals, he says. He set his sights on a wall in La Alma-Lincoln Park. But he needed permission to paint on public property. So he found a job with the city as a lifeguard. His plan worked and he was able to paint the mural.

Martinez also started an arts and crafts program for kids in the neighborhood. Martinez later founded the La Alma Rec Center. Eventually, he talked his way into a full-time painting gig with the city. Martinez says he made $3.50 and hour but had to get his own materials.

“And I’m probably the first and last full-time muralist the city of Denver has ever had,” he says.

5) ‘Confluent People’ Entered Denver’s Art Collection Sideways

The city’s approach to public art has evolved since Martinez got his artsy start as a city lifeguard. There’s now an official program that commissions pieces -- including murals -- all over Denver. And yet, Martinez’s works still stand out. Many pull from Mexican imagery, like the mestizo head, as a way to share what he’s learned about his heritage.

As for the popular “Confluent People,” it’s now part of the city’s public art collection. The interesting distinction? Denver did not commission it. Instead, the Greenway Foundation asked Martinez to create the mural with a grant from the Gates Foundation. It was later donated through a formal process to the city, which now maintains it.

The artist estimates that the mural has cost nearly $10,000. It’s grown far beyond the initial concept to include people of different races, genders and ages. Martinez hopes that resonates with people who see it.

“A mural is the most dynamic form of art because it reaches the masses and it belongs to everybody,” Martinez says.