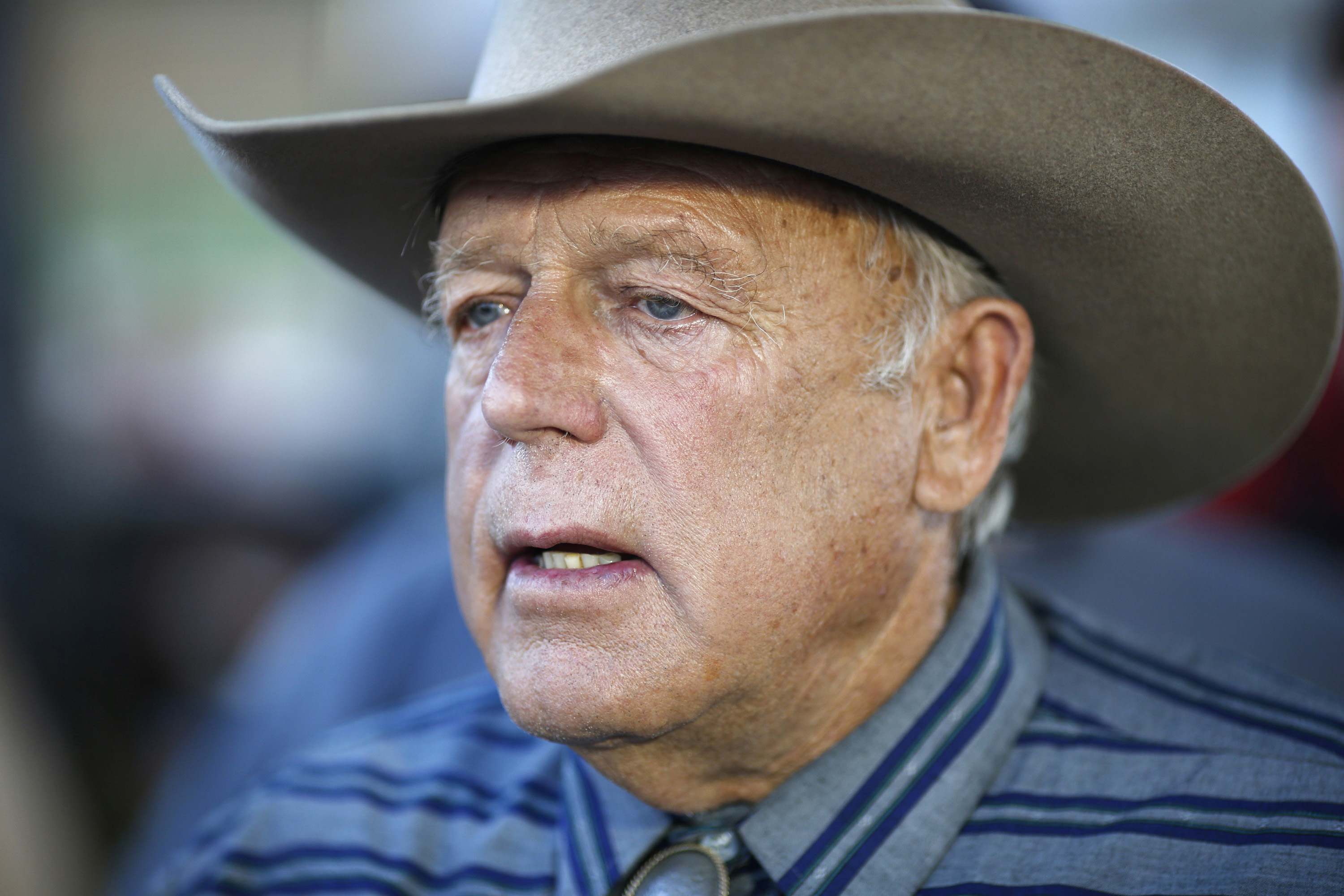

Jury selection ended this week in the trial of Nevada rancher Cliven Bundy. It's the latest chapter in his long-running saga of conflict with the federal government over intentionally grazing his cattle on public land while refusing to obey the law and pay for the privilege. It's also a conflict with a Colorado connection.

Most ranchers pay the grazing fee to have their cattle on public lands. At this point Bundy has racked up more than a million dollars in fees -- fees that are below market value -- paid for each head of cattle. But in 2014, Bundy and his sons led an armed standoff against federal agents in Bunkerville, Nevada, who came to enforce the law and impound his cattle. Bundy was arrested two years later.

Depending on the trial's outcome, anyone exploring public lands in Colorado and the rest of the rural West could feel its impact. Here's a recap of how the conflict came to court, and where it might lead:

This was a tough jury to select:

In early October there was the mass shooting in Las Vegas. The Bundy trial and jury selection was actually supposed to start in early October but the defense asked for the trial to be postponed. They worried that it would be difficult to put together a jury that wouldn't feel strongly about firearms.

Potential jurors were given questionnaires asking them about their feelings on guns and protests and the Oct. 1 shooting in Las Vegas. After the first day of jury selection, nearly half the original pool was gone. Twelve jurors and four alternates were selected Thursday. There are more than 1,100 potential witnesses in this federal trial and the judge has said the trial could go until February.

Bundy and his sons were in the courtroom this week and they chose to wear red jail garb even though they were offered regular clothes to wear. They said they were doing this as a sign of solidarity.

Why Bundy takes this position against the government:

“He’s the last vestige of the real old-time, set-in-the-mud western ranchers," says Charles Wilkinson, a distinguished law professor at the University of Colorado in Boulder and an expert on public land law. "He believes that he has a right to graze and that the government has no right to require him to pay a fee or get a permit and that he’s by god not going to pay or have the permit."

Where Bundy gets his ideas that he doesn't have to follow the law:

Cliven Bundy has said all along that this conflict isn’t about grazing fees. This is about state sovereignty and who has access and control of public lands. For him this is about what he defines as constitutional freedoms. The Bundy family says that their ancestors were some of the first Mormon settlers of Bunkerville, Nevada in 1877.

Bundy has said that before the federal government began managing lands in the West, the family had claims to this land and they inherited the authority to ranch. But to be clear, the federal government does have authority to manage public lands and this is something that the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld.

Colorado is the birthplace of a defining complaint over public grazing:

President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Gifford Pinchot to lead, in 1898, what became the U.S. Forest Service and he created the first modern regulatory law on public lands: If you grazed cattle on public lands you had to have a permit. Now, it was a tiny fee but ranchers were not happy.

Enter Colorado rancher Fred Light who grazed in what’s now the White River National Forest.

"So Fred Light decided he was not going to comply," explains Wilkinson. "But Fred Light was a gentleman. He called up the Forest Service supervisor [and says]. "Next Wednesday I’m going to drive my cattle onto the National Forest just like I’ve always have. If you want to try to stop me, fine. Let’s go to court against each other."

Light moved his cattle and the Forest Service gave him a ticket for failing to get a grazing permit and Light went to court "with the whole state of Colorado behind him to the extent the legislature paid Light's attorney fees to take the case to the U.S. Supreme Court," Wilkinson says. The court sided with the Forest Service, "Light had to get the permit and pay the grazing fee and Fred Light said OK, the court has spoken."

Bundy takes up arms against the government:

In 2014, the Bureau of Land Management tells Bundy that his cattle will be impounded, and Bundy states publicly he’s "ready to do battle" with the BLM and that he intends to organize people to come to Nevada in a "range war" against the BLM to protect his cattle and property. People from all over come to support the Bundys including militia members, and members of the so-called patriot movement. These are people who have strong beliefs about what the Constitution says about individual liberty. On April 12, hundreds of them, many armed, some carrying American flags on horseback, gather at this impoundment site in Nevada. The situation becomes very tense. The federal agents back off. No one is arrested. No shots are ever fired. And Bundy's cattle are released to the sound of cheering Bundy supporters.

Why Cliven Bundy is just now going to trial, and the charges he faces:

To understand that we have to look at what happened after the Nevada standoff. Cliven Bundy’s son Ammon was pretty inspired after the stand off and he led occupiers at the takeover of the Malheur Wildlife National Refuge near Burns, Oregon. He and his brother Ryan were arrested and later acquitted on felony charges that ranged from conspiracy to keeping federal employees from doing their jobs to possession of firearms in a federal facility. Now Ammon and Ryan face similar charges along with their father.

Cliven Bundy wasn’t directly involved in that Oregon takeover but he was arrested in February of 2016 in Portland, Oregon. Bundy, who’s now in his 70s, faces a number of charges including assault on a federal law enforcement officer, using and carrying a firearm in a relation to a crime of violence, obstruction of administration of justice and interference with commerce by extortion.

The trial involves other people in the Bundys' orbit:

It also includes Ryan Payne, one of Bundy’s supporters from Montana and a militiaman. This federal case against Cliven Bundy alone includes 18 co-defendants. Some of these people have been acquitted for their part in the 2014 standoff or sentenced.

Cliven Bundy could be looking at many years behind bars:

Perhaps five years in prison on the conspiracy charge alone and up to 20 years in prison on the assault on a federal law enforcement officer and interference with commerce by extortion charges. There’s another 10 years he could get for obstructing justice and the list goes on. He also could be dealing with fines up to $250,000 per count.

The case is being so closely watched by anyone concerned about public lands:

This trial is the culmination of all of this drama and tension that boiled over in Bunkerville. It’s a truly western story and ultimately it comes down to a fundamental question that’s been brewing for some time and that’s who should really control and manage public lands. Remember for Cliven Bundy this stand off and his decades of not paying grazing fees isn’t really about the fees. It’s about who has the right to control public lands and some states like Nevada, Utah and Idaho believe that states are better equipped to manage these lands. Cliven Bundy for instance has said he’d pay fees to the state or the county.

Now in Colorado the governor has been clear that he doesn’t believe that states can do a better job than the federal government so we’re not likely to see this play out here.

And there are high stakes involved in this case that stem around the standoff and this use of violence and intimidation that we saw in Nevada and also Oregon. Let’s say the jury decides to acquit Cliven Bundy like his sons Ammon and Ryan in Oregon. There’s a big question about how such an acquittal could be interpreted. Would such a decision give people the ok to use firearms against the government if they don’t like a rule or regulation on public land? It’s a big question and one we’ll likely have more insight on in four months. That’s how long the judge expects this trial to last.