Editor's Note: This essay is part of a collaboration between Colorado Public Radio and the Center of the American West at CU Boulder. Authors B. Erin Cole and Allyson Brantley are, respectively, the assistant state historian at History Colorado and a Ph.D. candidate at Yale University working on a dissertation about the Coors boycott.

For some Americans in the 1960s and 1970s, Coors — the iconic Rocky Mountain brew — signified views about labor, race, and gender equality. The Coors boycotts, beginning in 1966 and lasting, for some people, right up to the present, connected a wide spectrum of activists and organizations, much like the successful grape boycott organized by Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers in the 1960s.

Opposition to the Adolph Coors Company centered around three issues. First, the company did not get along with organized labor. Second, critics charged that Coors hiring practices discriminated against Hispanics, African-Americans, women, and gays and lesbians. Finally, members of the Coors family, particularly Joseph Coors, actively supported and funded conservative politicians and organizations. For liberal activists, any one of these issues was enough to avoid purchasing a cold can of Coors, but the three together meant there was no conscionable reason to drink anything brewed with Rocky Mountain spring water.

The boycotts began locally. In 1966, members of the Denver-based Crusade for Justice and the Colorado chapter of the American GI Forum, the national Hispanic military veterans’ association, organized a boycott of Coors beer to protest the company’s poor treatment of Mexican-Americans.

Only 2 percent of the approximately 1,400 workers at the company’s Golden brewery were Mexican-American, and those Hispanics who found employment were stuck in poorly paid, menial jobs. The brewery subjected potential employees to polygraph and other tests to “detect possible troublemakers” – a policy instituted by the family after the kidnapping and murder of Adolph Coors III in 1960.

GI Forum members met with company chairman William Coors several times to discuss these problems to no avail. In August 1970, the Colorado Civil Rights Commission ruled against Coors in the case of an employee who argued he had been fired because of his race.

For many Hispanics, the reasons for the boycotts went deeper than employment discrimination. The Coors family supported grape growers who resisted the labor demands of the United Farm Workers. El Gallo, the Crusade for Justice’s newspaper, ran the headline “Chicanos Stop Buying Coors!” along with photographs of Coors trucks reportedly transporting “scab” grapes to market.

Activists also took issue with Joseph Coors’ opposition, as a regent of the University of Colorado, to the establishment of Chicano studies courses, the presence of United Mexican American Students on campus, and other forms of student activism.

Protests against Coors took place across Colorado. In 1969, 43 Chicano students at Southern Colorado State College (SCSC) - now Colorado State University-Pueblo- joined hands around the campus pub to keep people from ordering any Coors beer. Fifteen students were arrested, and the SCSC administration got a restraining order prohibiting any of the protesters from “interfering in any manner whatsoever with the operation or sale of 3.2 beer.”

Protests soon crossed Colorado’s borders. The same year as the SCSC boycott, the American GI Forum called for a boycott of Coors that would last a decade. Other Hispanic and Chicano groups supported the Colorado and national boycotts. The boycotts helped build bridges between Chicanos and other marginalized groups affected by the Coors Company’s hiring practices.

In the 1970s, boycotts of Coors continued to grow. In 1977, the AFL-CIO called for its member unions to boycott Coors to support striking workers at the company’s Golden brewery. The Coors family had long opposed organized labor, having brought their employees’ Local 366 of the Brewery, Flour, Cereal, and Soft Drink Workers International Union into line after a failed 1957 strike.

Despite their ineffectiveness, Local 366 helped Coors market its product to working people. Stagnant wages in the face of inflation, and demands for the company to end intrusive polygraph tests sent 1,400 members of Local 366 back to the picket lines in 1977. Coors responded by hiring non-union replacement workers, and forcing an election to decertify the union.

The company won the strike, forcing Local 366 to dissolve, but the AFL-CIO boycott went on for another decade. It brought together, once again, groups that had always opposed Coors’s hiring and union-busting practices, including feminists, Hispanos, African Americans, and members of the LGBT community – the last specifically objected to Coors specifically screening for homosexuality during its hiring process. The boycott extended as the company expanded its distribution network outside of the West; bartenders served Coors beer with a controversy chaser in communities across the country.

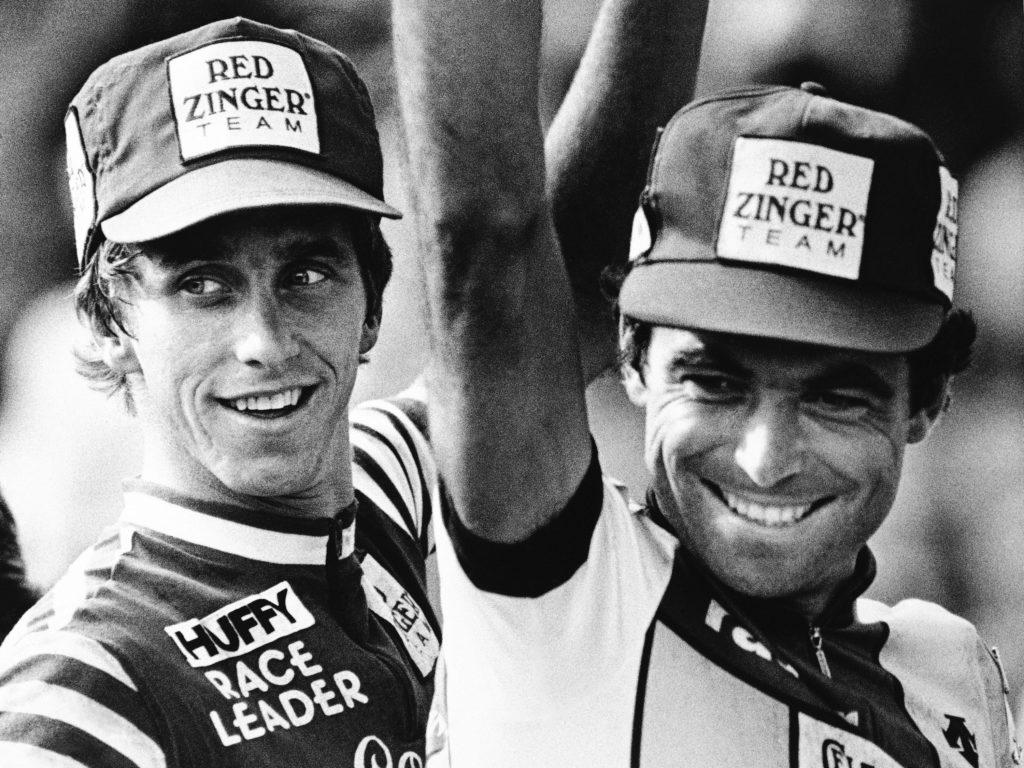

Protesters stake out Coors-sponsored cycling race

By Allyson Brantley

Decades before the USA Pro Cycling Challenge became one of the country's largest road cycling race, Coors became the title sponsor of its predecessor -- the Coors Classic. From its humble and cheap beginnings in 1979 to its final run in 1988, the Classic became an internationally renowned two week long racing event, which showcased Colorado’s landscapes, from a stage through the Colorado National Monument known as the “Tour of the Moon” to another up the steep “Suicide Hill” near Snowmass.

Considered by many to be one of the “toughest bicycle races in the Western Hemisphere,” the Coors Classic was a confluence of Colorado’s best-known qualities: outdoor recreation, idyllic scenery, and Coors beer.

Coors’ sponsorship of the Classic, however, brought a good deal of controversy, pickets, and protests along with it. On the evening of July 31, 1980, in a large multipurpose room on the second floor of the University Memorial Center at CU Boulder, a group of student, labor, and community activists rallied behind the slogan: “Bikes Forever, Coors Never!”

The race presented an opportunity for activists to publicize their reasons for boycotting Coors – and what they saw as a disconnect between the Classic (and a vision of an athletic, scenic, and pristine Colorado) and the Coors Brewing Company’s “union-busting” and anti-environmental policies and practices.

A flier distributed in 1980 asked fans and spectators, “What do bicycle races, boycotts and beer have in common? All three are produced by Coors. You may have wondered why Coors took such a sudden interest in bicycle racing. It’s all part of a $60 million campaign to combat a national boycott endorsed by labor, women, students, Chicanos and many others offended by Coors over the years.”

Yet while boycotters saw Coors’ sponsorship as a disingenuous marketing ploy, they affirmed the important role of bicycles and the race in their community and insisted their protests were only directed at Coors and not cyclists.

These protests did not defeat the Coors Classic in 1980. The race continued but in 1988, Coors withdrew its sponsorship for logistical and financial reasons. Up until the Classic’s last run, boycotters from Hawaii to Colorado hoisted boycott signs and distributed fliers. Their shouts and signs highlight the important, contested, and intertwined histories of beer and sport in Colorado’s past and present.

Boycott wound down in late 1980s

The boycotts had a clear financial impact. In California, where anti-Coors sentiment was high, the company’s share of the state beer market slid from 40 percent in 1977 to 14 percent in 1984. Company profits also dwindled during this time, both to the boycott and increased competition from other breweries.

The AFL-CIO and Coors came to an agreement in 1987, ending the official union boycott. But grudges against Coors continue, even though the company has an improved record of hiring minorities and women, and has reached out – both financially and through marketing – to communities that once actively boycotted its products.