When Colorado voters get their mail-in ballots for November, chances are they’ll find one or two different asks from schools looking for money. Either a bond initiative to pay for buildings and repairs or a mill levy override to raise local property taxes to pay for programs, materials and teacher salaries. Or in some cases, both together.

Why is this likely?

Because it’s a presidential year and because there are about 62 different measures spread across 44 school districts, according to the Colorado School Finance Project. These schools want to take advantage of high voter turnout to try and get back to the funding levels they had before the Great Recession. A cost-cutting mechanism created by the legislature – known as the ‘negative factor’ – has led to a total shortfall of more than $5 billion since the recession. Those cuts came with a promise to pay it back.

That hasn’t happened, meaning a district like Denver Public Schools received less funding per pupil in 2015 than it did in 2008. For most districts, the negative factor amounts to a 13 percent cut.

Denver is a place where there are two asks on the ballot, a $572 million bond measure and $56 million mill levy. The bond measure would pay for classroom expansion in the rapidly expanding north east, additional computers, and for school upgrades and air conditioners in older schools. The property tax ask, about $10 a month on the average home, would pay for early literacy programs, teacher training, along with psychologists, social workers and nurses.

Similar to Denver, Jefferson County has a $535 million bond ask on the ballot. It would create a three-grade middle school system to relieve overcrowding, as well as pay for repairs and improvements to 100 school buildings. Backers of the measure say other districts have passed local property tax increases, allowing them to keep up with their own needs. Superintendent Dan McMinimee notes that if his district had the same mill levy funding per student as Denver, JeffCo “would have $26 million more.” If it matched up with Boulder, the district “would have $71 million more.”

While most district measures don't have organized opposition, Jen Butts with the group Jefferson County Students First said the property tax hike is just too much for small businesses. She said there aren’t clear enough targets for how building improvements will raise achievement.

“Whatever it is that you want to put into that building, you should be able to quantify how that’s going to improve the life of your child,” Butts said.

Like Jeffco, Adams 12 Five Star has an overcrowding dilemma. The district that serves Thornton, Northglenn, Broomfield and Westminster has added 4,200 students since its last bond measure – 12 years ago. At Rocky Top Middle School, for example, there are four full classes divided by temporary walls in the school library. Another class is held in a hallway. The school’s principal, Chelsea Behanna, said the ideal school size would be about 300 students less than they have now.

“There’s a difference, a palpable difference in the hallway of a middle school when there are nearly 1,400 of them passing during a 4-minute passing period at different parts of the day and it is very stressful from a safety and security standpoint,” Behanna said.

If the Adams 12 bond passes some of the students from Rocky Top would go to a new K-8 school. The bond would also help the district with the upkeep on the buildings it has, taking care of rotting pipes and leaking roofs.

The measure would not raise the current bond tax rate because the district has paid down and refinanced existing debt. If the bond doesn’t pass, the district said it would have to cut staff in order to address critical repairs related to safety and security. The result may be that classroom sizes could grow and school boundaries will have to shift.

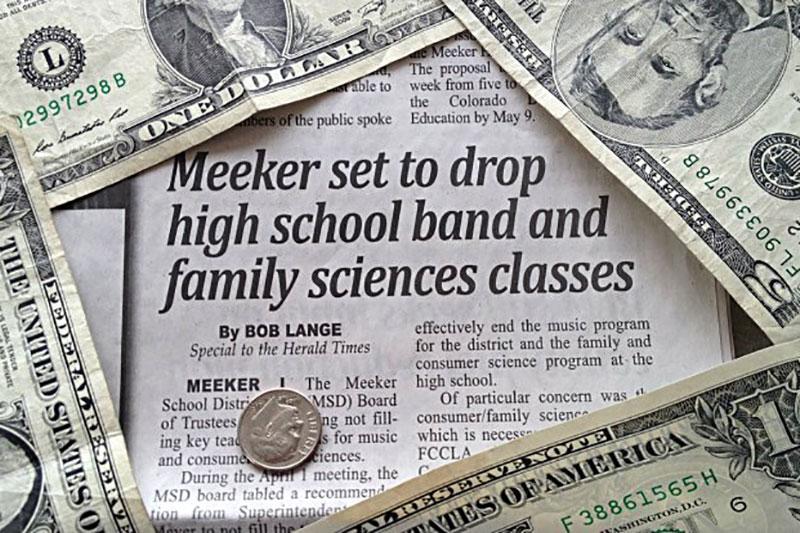

In smaller districts, the funding crunch is a little more severe. On the Eastern Plains, rural Caliche Junior-Senior High is looking for infrastructure improvements and money for programs and teacher retention. On the other side of the state, in the Yampa Valley’s Hayden School District, Superintendent Phil Kasper is looking to replace school buses. The region relies on ranching and jobs at the coal-fired power plant. With locals nervous about the future, Kasper feels that buses are all he can ask for.

“There’s no relief in sight to keep teachers, pay teachers, maintain libraries, maintain arts, maintain band,” he said.

The district’s buses put on a lot of miles, almost 14,000 a year, and often on gravel roads. One of the buses has 260,000 miles on it.

“I don’t know where we’re headed, I mean, it’s hard to be optimistic right now,” Kasper said, adding that districts have been told to brace for further state cuts next year.

One superintendent is working hard to be optimistic. Cripple Creek-Victor RE-1 in the mountains west of Colorado Springs is in a similar situation to what Hayden might soon face. It lost $55 million dollars in assessed valuation which lowered property tax revenue when the region’s gold mine changed hands. The district had to dip into their reserves, almost half of them in fact.

“We withdrew basically $500,000,” said Leslie Lindauer.

His district is seeking a mill levy override to stabilize revenue shortfalls, help keep teachers from leaving for the Front Range and to expand vocational training for students. His optimism though comes from his focus on trying to solve the school finance problem rather than “focusing on poor me.”

He brought up the idea of a commerce tax, similar to what Nevada has. It’s a tax on businesses that make over $4 million. With Colorado’s existing TABOR law, backers of more education funding would have to amass political support to bring it to the voters of Colorado. Since TABOR came into being in 1992, voters have passed just two statewide taxes – on tobacco and pot.

In the meantime, each of the school districts is hoping that voter turnout generated by the contest between Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton will translate into funding that will cover school programs, materials, salaries and school operations.