When you think of an angst-filled werewolf, maybe this scene from "Twilight: Eclipse" comes to mind:

In other films, werewolves are much more ruthless. Here's a clip from the trailer of 2010s "The Wolfman."

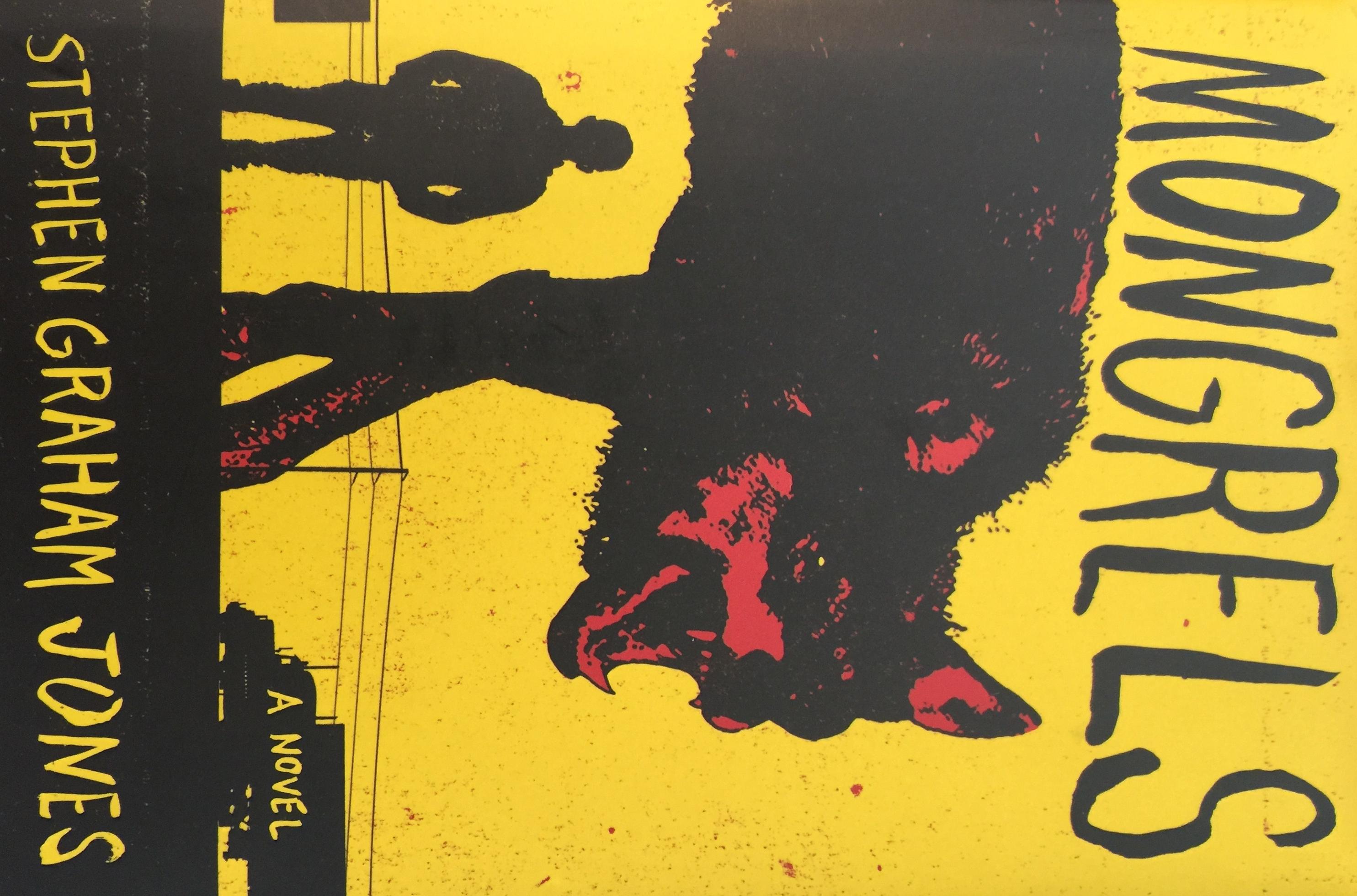

In his new book "Mongrels," Boulder author Stephen Graham Jones introduces us to his version of the werewolf -- much less Hollywood killer, and much more nuanced.

He spoke to Colorado Matters host Nathan Heffel.

Read an excerpt:

My grandfather used to tell me he was a werewolf. He’d rope my aunt Libby and uncle Darren in, try to get them to nod about him twenty years ago, halfway up a windmill, slashing at the rain with his claws. Him dropping down to all fours to race the train on the downhill out of Booneville, and beating it. Him running ahead of a countryside full of Arkansas villagers, a live chicken flapping between his jaws, his eyes wet with the thrill of it all. The moon was always full in his stories, and right behind him like a spotlight. I could tell it made Libby kind of sick. Darren, his rangy mouth would thin out in a kind of grin he didn’t really want to give, especially when Grandpa would lurch across the living room, acting out how he used to deal with sheep when he got them bunched up against a fence. Sheep are the weakness of all werewolves, he’d say, and then he’d play both parts, growling like a wolf, his shoulders pulled up high, and turning around to bleat in wide-eyed fear, like a sheep. Darren would just shake his head, work another strawberry wine cooler up from beside his chair. Darren was the male version of my mom and Libby—they’d been triplets, a real litter, according to Grandpa. Darren had just found his way back to Arkansas that year. He was twenty-two, had been gone six magical years. Like Grandpa said happened with all guys in our family, Darren had gone lone wolf at sixteen, had the scars and blurry tattoos to prove it. He wore them like the badges they were. They meant he was a survivor. I was more interested in the other part. “Why sixteen?” I asked him, after Grandpa had nodded off in his chair by the hearth. Reprinted from MONGRELS by Stephen Graham Jones with permission from Wiliam Murrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Copyright (c) Stephen Graham Jones, 2016. |