It may seem that Colorado is flush with public lands — and to some degree, that’s true. In tiny Costilla County, though, more than 99 percent of the land is in private hands.

County officials have known for a while that the lack of public lands here is a problem on several fronts; a lack of recreation and the tourism dollars it brings, for one. In a county full of history, the new San Luis Hills Wildlife Area hopes to make some of its own.

There are Spanish and Mexican land grants around San Luis, the state’s oldest town, that predate Colorado statehood back to the Mexican-American war. That’s where the county’s lack of public land all began, with the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which decreed “the U.S. would recognize land grants, but they didn’t do it across the board, each individual land grant had to petition the U.S. Supreme Court,” says Costilla County administrator Ben Doon.

Costilla is historically a part of the Sangre de Cristo land grant, bestowed by a newly-independent Mexico to thwart U.S. westward expansion. Prior to that, it was part of Spain’s original New Mexico territory. In 1860, that land grant was upheld by the Supreme Court.

“A whole huge area of the county and beyond was basically owned by one person at that time,” says Doon, referring to Carlos Beaubien, a judge who later determined how the land grant would be meted out to families, even carving out spaces for communal grants. Many of those grants are in effect today, belonging to “heirs” who graze their animals and gather firewood on certain tracts.

Over the next 100 plus years, many grants were subdivided and granted or sold to other private owners. Today, while Costilla County has only 3,524 residents, Doon says there are more than 45,000 landowners, mostly absentee. The county is home to Mount Culebra, one of the state’s only privately owned 14-ers. In 2017, it was listed for $105 million.

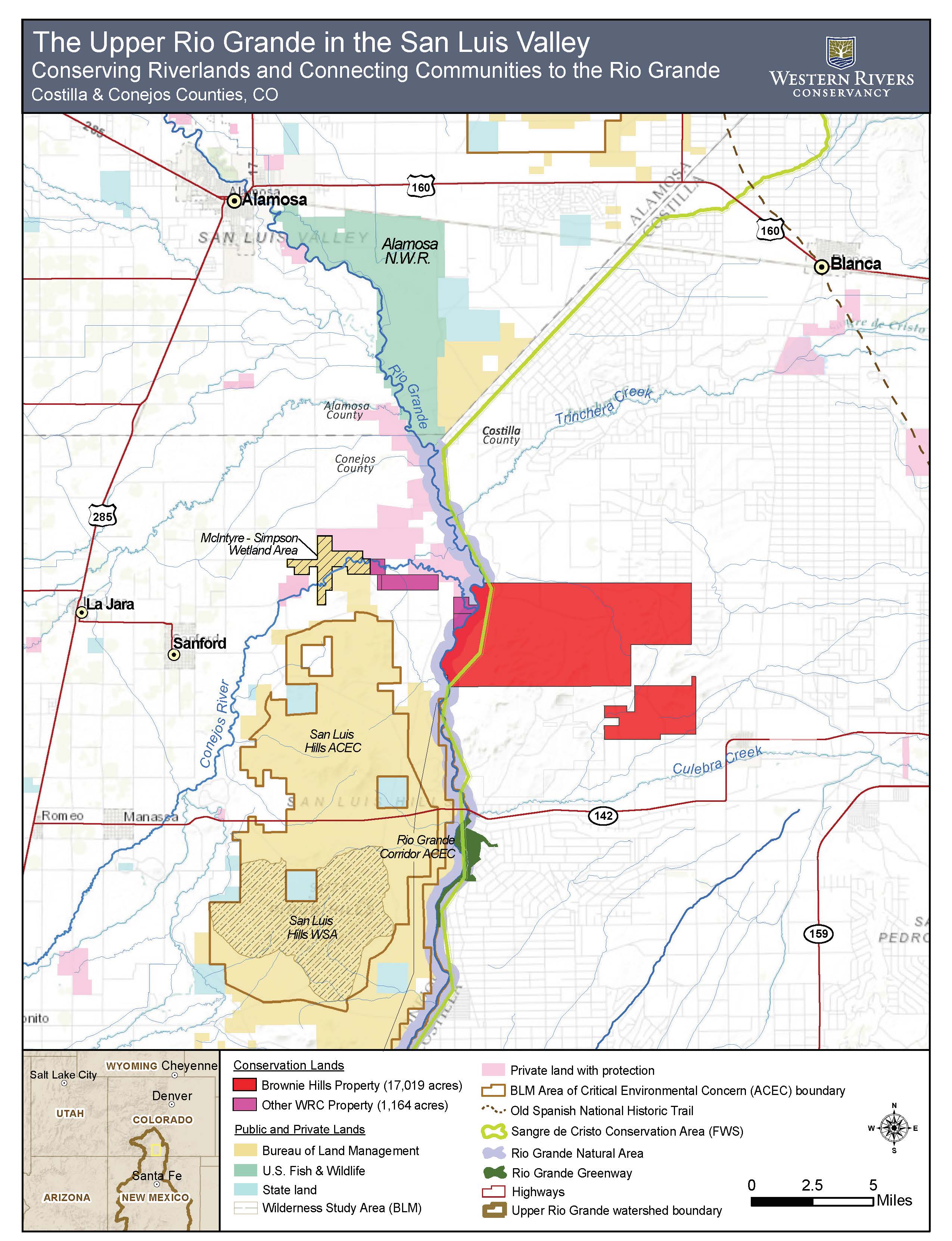

If you look at a map of Colorado Forest Service or National Park Service land, “Costilla County looks like a little white thumbprint,” Doon laughs. “You know, it’s shaded green for Forest Service land, brown for [Bureau of Land Management], pink for [National] Parks Service land and white’s private, and we’re just one big white spot.”

In 2012, a property called Brownie Hills was identified as possible open space. It’s a sprawling 17,000 acres, just west of San Luis, left largely unused for years, and held by an absentee owner. Hemmed between a few ranches and farms, it features rolling valleys of rabbitbrush, huge sloping hills and a nearly five-mile sliver of the Rio Grande river — huge for a county where public access to the river is fairly restricted.

Costilla County could have probably afforded to buy just a small slice of the land. That’s where Dieter Erdmann and the Western Rivers Conservancy came in.

Erdmann’s nonprofit identifies key rivers in the United States and work to put river lands into the hands of local governments, or other conservation partners.

“When that valued piece of private property goes on the market, we have the ability to step in and secure that and develop a plan for an orderly transition of that property to habitat conservation, public access, etc.,” Erdmann says.

The Conservancy bought up the land as “transitional stewards” and then offered it to Costilla County. That set into motion a process that ultimately created the San Luis Hills Wildlife Area — all 17,000 acres of it.

The state’s newest wildlife area is a big team effort. Western Rivers Conservancy helped the county raise the $3.5 million needed to purchase the land. Great Outdoors Colorado provided some funding too, on the condition that it remain publicly accessible forever. The county didn’t have the means to manage the space alone, so Colorado Parks and Wildlife stepped in to help. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service also put a conservation easement on the property, preventing any future landowner from making significant changes.

But the real conservation work has only just begun.

Fish and Wildlife is interested in the land mostly because it provides a habitat for two endangered bird species: the southwest willow flycatcher and the yellow-billed cuckoo.

To help bolster their numbers, Colorado Parks and Wildlife is working to replenish the willow trees that normally grow along the Rio Grande. They are starting to recover thanks to a fence they installed along a strip of land that borders the river. The fence keeps out feral horses, which wildlife manager Rick Basagoitia says are the biggest challenges to rehabilitation.

There are “animals that exist out here eating the vegetation that they can find to make a living,” Basagoitia says, adding that Parks and Wildlife has been struggling with feral horses on multiple fronts across the state.

These are not wild horses, they’re abandoned domestic horses. Most are malnourished. They reproduce a lot. The agency estimates more than 700 roam the property freely, overgrazing already taxed resources.

“Having these many horses on this landscape just doesn’t allow it to recover,” Basagoitia says. “We’re also in the midst of a long-term drought, so that doesn’t help the situation.”

San Luis Hills Wildlife Area is already open for hunting and recreation, although the plan is to keep things primitive. Aside from signage, no trails or campgrounds will be built in here, although backcountry camping will be allowed.

Looking for Colorado’s latest wildlife area? You can get there by driving west on CR 159 to CR 142 from San Luis. From Alamosa, drive south on U.S. 285, then east on CO-142.