Something unexpected has happened with several years of teacher and principal evaluations tied to student performance: Teachers may be doing too well.

Colorado’s teacher and principal evaluations program, passed by the legislature in 2010, was among the first of its kind in its country because it made adjustments to teacher tenure and based 50 percent of job performance reviews on student performance. The other half is based on a supervisor’s review.

This all means early teachers have a higher hurdle than they used to in obtaining tenure and they must demonstrate growth in a classroom in order to keep their jobs. When it passed, the law drew a national firestorm and resulted in several lawsuits.

Since the law has been implemented, though, the data shows most Colorado teachers passing. In the most recent numbers based on the 2014-2015 school year, 96 percent of teachers evaluated received a rating of effective or higher. Almost no school districts had any “ineffective” teachers and only five principals in the state were rated “ineffective.”

One education reform advocate compared it to the fictional Lake Wobegon, where everyone is “above average.”

Britt Wilkenfeld, who directs research at the Colorado Department of Education, said the focus should be on the how the law has shifted conversations between principals and teachers statewide.

“Some people do focus more on the ratings … is it really representative, is that really true?” Wilkenfeld said. “I do think the information is helpful.”

Wilkenfeld points out that before the law, 99 percent of teachers statewide achieved tenure — many of whom didn’t have to show any student growth for that.

Sarah Almy, director of talent management at Denver Public Schools agreed. In DPS, about 88 percent of teachers were rated “effective” or “distinguished.”

Asked whether she thought those numbers were accurate, she said, “it’s hard for us to know.”

“One of the things we’ve spent a lot of energy on and time on is really around making sure we have common definitions,” she said. “That’s a challenge across 150 schools.”

The idea of tying student achievement directly to educator evaluations came from former state senator Michael Johnston, who is now a Democratic gubernatorial hopeful. Johnston’s system was inspiring to former education officials in the Obama administration and several states across the country created similar programs, looking to Colorado for guidance.

Johnston said the conversations taking place in schools between principals and teachers are an improvement — even if the early data is not as helpful.

“It was never a goal or intention of we want to find this many teachers who are good and this many teachers who are bad,” Johnston said. “We just wanted to have information to help teachers get better … The purpose was going to be can we get better data to help teachers improve?”

But Rob Stein, the superintendent of the Roaring Fork School District, said the entire process is time consuming and unhelpful in improving education at his schools. Stein originally favored the idea years ago and even helped pass it at the legislature.

“They went after this very complicated system,” he said. “And it’s turned it into this sick game where you end up having a conversation about how you get the points instead of let me just give you, like a coach on a field, let me give you a few pointers to help you improve and try that out.”

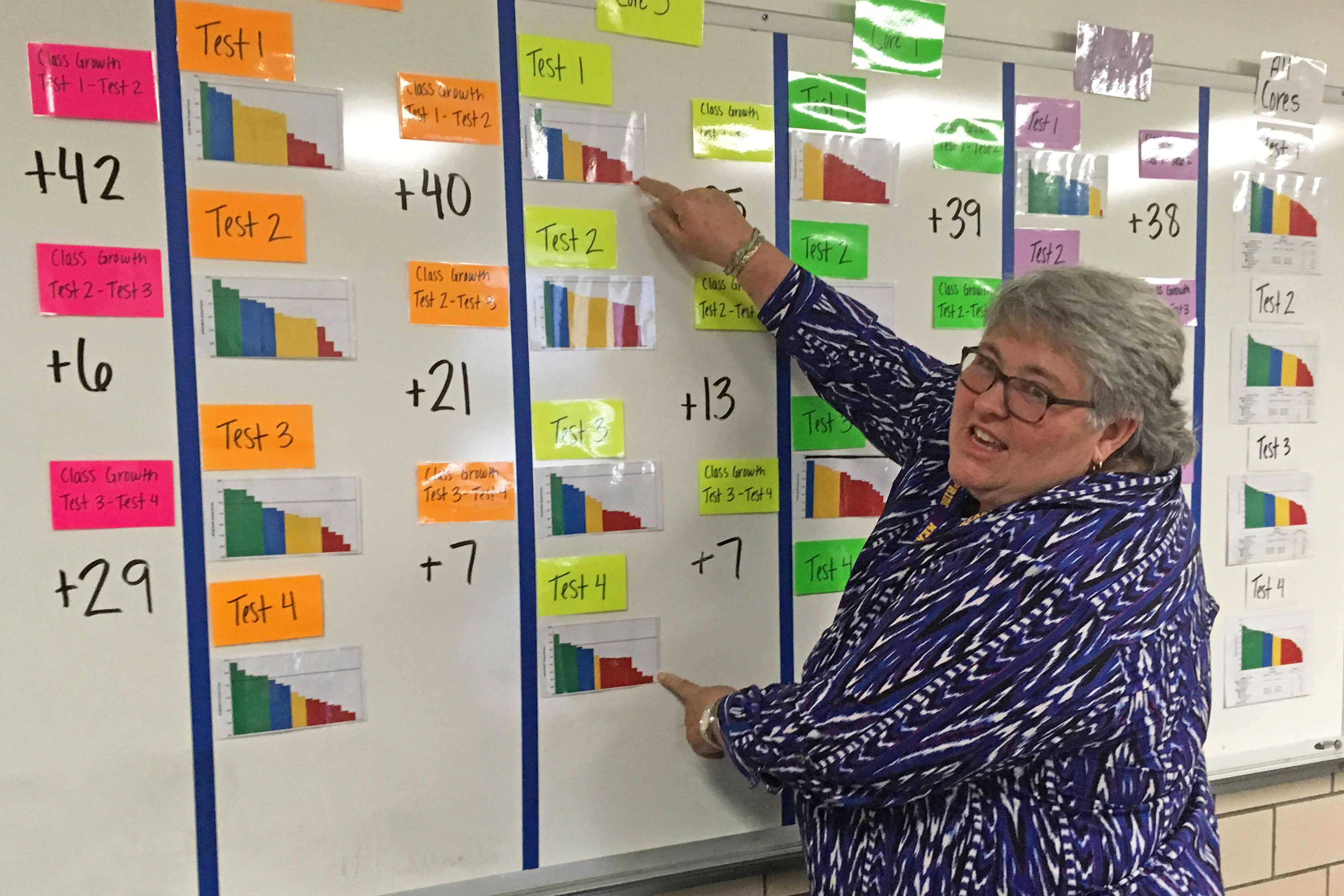

BJ Jeffers, principal of Kearney Middle School in Commerce City, has embraced the evaluations and measurements. There are student growth numbers all over the walls of her high-poverty school and office that show where teachers need to improve and where teachers are doing well.

Jeffers said the conversations have been helpful, even if they don’t tell an entire story about a child.

“Our kids are resilient and they are amazing, but they’re coming to us with much, much more than any child their age should have to have seen or witnessed,” Jeffers said. “Numbers won’t reflect that.”