Britt Westmoreland was assisting a pregnant mother who was in long-term recovery from substance use disorder and about to have her second baby.

After meeting once a week during the pregnancy, Westmoreland, the Recovery Coach Doula Program Coordinator with University of Colorado College of Nursing, was in the room for the birth. The mother had been prescribed a drug that helped her control cravings.

Suddenly, the labor and delivery nurse said something that did not surprise Westmoreland – something that nonetheless made the mother feel guilty.

According to the nurse, any negative issues in the delivery experience were due to the drug. Westmoreland knew this was wrong, so she rushed to find a doctor, who came into the room, corrected the statement the nurse had made. The doctor said the drug she was taking wasn’t a problem – the nurse was mistaken and the drug was approved for use during pregnancy.

“I learned the increased stigma and bias that specifically birthing people and mothers experience who have substance use disorder,” Westmoreland said. “There’s this unfortunate belief system that pregnancy should, or motherhood should, cure substance use disorder – that if you care about your child, then you wouldn’t be having this problem ... it leads them to be treated poorly in different spaces, including labor and delivery.”

Recovery Coach Doula Program

The nursing school at CU Anschutz in Aurora launched the recovery coach doula program in January 2023 with funds from the Colorado Attorney General Opioid Response Strategic Impact Grant. Funds will expire next year, in September 2026. As of February, the program has received at least 150 referrals and has supported at least 77 new parents.

Recovery coach doulas like Westmoreland are selected for their jobs because they themselves have battled a substance abuse disorder. Westmoreland, who said she has a 4-year-old son, is in recovery from an addiction, she said in an interview.

Her past, which makes her a compassionate and understanding person for the role, also works against her. She said she had a “remote” smudge to her criminal record from a long-ago charge she did not specify.

In order to benefit from a new law passed last year that would allow her to gain access to reimbursements from insurance companies, she has to pass a background check, and if she doesn’t, she cannot recoup the funds, which come out to about $1,500 per client.

The new law

In 2024, Colorado passed a bill into law making it possible for the care of doulas to be covered by insurance. The Coverage for Doula Services was sponsored by Sens. Rhonda Fields and Janet Buckner, and Reps. Regina English and Junie Joseph.

A doula role is different from that of a midwife, who has more training and can “catch” a baby without the support of other medical providers, while doulas serve alongside health care providers but don’t do deliveries alone.

It’s unclear how many doulas there are in Colorado, because there is not a registry or centralized association, but the cost of doula services in Colorado – prenatal and post-natal care and delivery – is about $1,500. Currently, Medicaid is the only insurer doing reimbursements.

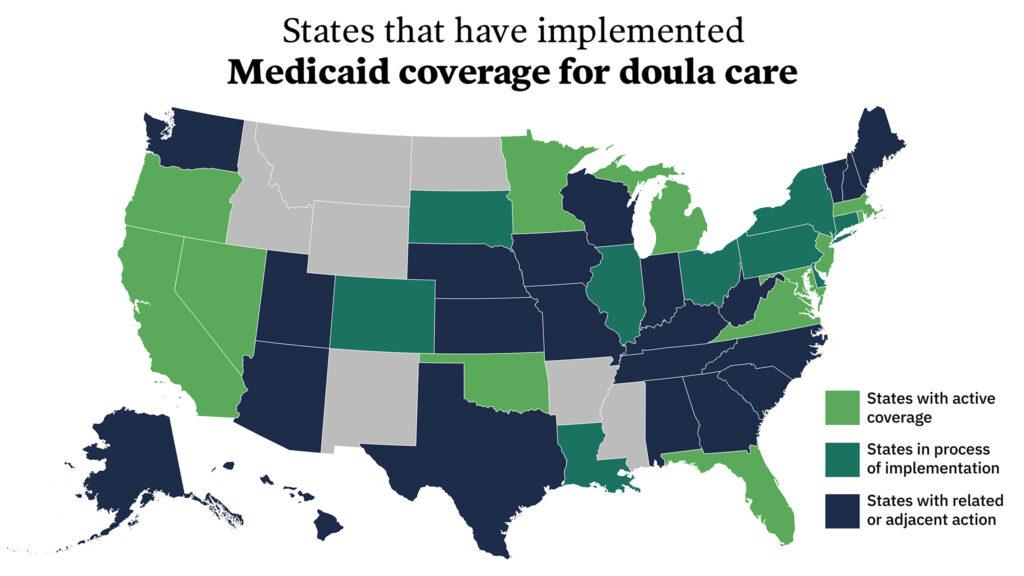

Other states that have similar legislation in place allowing reimbursement for doula care include Oregon, Minnesota, Florida, New Jersey, Virginia, Nevada, Maryland, Rhode Island, Washington, D.C., Michigan, California, Oklahoma and Massachusetts. However, it’s unclear whether any of these states has a recovery coach doula program like Colorado’s at CU Anschutz.

Lived experience helps mothers

The challenge arises insofar as recovery coach doulas bring “lived experience” to their role, meaning they have dealt with substance abuse disorder themselves – and some may have gotten a criminal record during their period of addiction that follows them to their new roles.

“Most of us have a lot less stigma and bias towards people in recovery because we have been there; we understand what it feels like, and we can show people that it’s possible to get out [of addictions],” Westmoreland said in an interview.

She works 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. and earns about $50,000 – with funds from the grant that lasts another year. She spends her days helping new parents with anything from giving birth to facing the loss of their newborn because of drug use.

“In some cases, we can’t stop the inevitable, which might be the hospital calling [Child Protective Services],” she said, adding that her role in such cases is “explaining everything that might happen, making sure they’re prepared, [walking] through it with them.”

The barrier she’s facing in accessing the benefits of the new law can be put into two words: Background check. She said she began recovery from her own substance abuse disorder in 2017, and then had a son four years later. Without specifying, she said she has a criminal record that is “remote.”

“None of us have been approved yet ... I’ve been trying for a little less than a year ... I do know there’s a background check involved, and evidently my background check was lost ... So having to go through that whole process again is one barrier that I’m facing.”

A third party helped with her paperwork a year ago when the law passed, and since then, she said she’s still waiting to hear back. If she and other recovery coach doulas are tripped up by their criminal records, that could interrupt the program she coordinates.

“If there’s no movement with billing at that time and grants run out and we don’t have more grants, then the program would have to dissolve, is my understanding,” she said.

Law still has challenges

The barrier based on background checks isn’t the only one doulas are facing, according to Sarah Lopez, a community doula for Elephant Circle, an organization based in Palisade, Colorado that supports birth justice through coaching, consulting, workshops and doula services.

For example, she said, private insurance isn’t a part of the program yet.

“Currently, it's only Medicaid that is under the law to cover for doulas,” Lopez said in an interview. “I think private insurance is supposed to have it up and running by this July,” she added. “I think sometimes that's because private insurance is like, ‘Well, let's see what Medicaid does and then we'll copy that.’”

Another issue: lack of uniformity in training requirements. Doulas in Colorado get about four days of training. Medicaid has different demands on doulas.

“They do require certification or proof that you have attended at least, I think, 10 births, and then they require things like you have to be a [Limited Liability Company],” Lopez said. “You have to have insurance coverage; you have to take a CPR course ... I know for many doulas, some of those things are barriers because we haven't been regulated and we've just been able to kind of be out there doing our thing.”

Besides the background check and training issues, there’s another obstacle: overlap. Doulas can only seek reimbursement for only one type of care, even if they provide care in several areas.

For example, Lopez said, some doulas are trained to provide additional services to a brand new parent – as a midwife and/or lactation consultant.

“So basically, Medicaid is saying, ‘You have to pick one, and we're going to only pay you for one. You can't be all of these things,’” she said. “So that's a barrier and a bummer because ... you can provide your clients with so much more care ... and access to many things [but] now they're telling us ... ‘you can only be one kind of provider.’”

Given some of the challenges in applying the new law, some people just aren’t bothering. “A lot of doulas are just kind of turned off by it and don't want to sign up for it,” Lopez said.

What the future holds

Brie Thumm, a birthing justice advocate and trained midwife who now works as an assistant professor in CU Anschutz’s nursing program, where the recovery doula program is based, said that despite the problems, she’s keeping an eye on how the law will work. “It’s a little clunky,” she said, “getting the legislation to actively be in place and reimbursing is taking time.”

“I feel about some of these legislations, it’s a great idea, but if you don’t have the mechanisms to bill for it, which is incredibly complex, labor intensive, resource incentive,” Thumm said, “then it doesn’t really matter that Medicaid’s paying, if there’s not a way to get that billing to Medicaid and then have a way to be reimbursed.”

In the meantime, she said, the recovery coach doula program Westmoreland coordinates is finding ways to work around the new law’s restrictions. With additional grant funding from other sources and expansion into Fort Collins and Pueblo, there’s a chance that the recovery coach program could endure with or without doulas’ ability to make use of the new law.

Westmoreland hopes the recovery coach doula program will endure whether the access to insurance reimbursements is resolved or not, because of the service recovery coach doulas can supply. The length of care is about one year – but she feels like what she was able to offer the mother who was battling addiction will endure.

After helping the new mom using a craving-reduction drug during delivery, through the “guilt that she felt around the medication she was taking, which was safe and everything for pregnancy and breastfeeding,” she also helped make the toddler she already had feel like she wasn’t losing her place.

“We talked a lot about the stress of now having a toddler and a baby or her apprehension around it. We talked a lot about ... how to incorporate the toddler into the baby's world ... [I] really just made sure that my client, the mom, had the support in place [and] knew who she would reach out to when she needed help.”

Funding for public media is at stake. Stand up and support what you value today.