In early June, 83-year-old Charles Collins took stock of his homestead near Galeton, a small town in Weld County, just northeast of Greeley. He surveyed the horizon for thunderstorms while Dusty and Pete, his cat and dog, rested on the porch.

“My wife and I are kind of, by virtue of our age, neighborhood pioneers,” said Collins, a retired University of Northern Colorado professor who taught geography for decades.

“I grew up in this neighborhood, so I've been essentially around here for 80 years,” Collins said.

The area around Galeton is dotted with oil and gas wells, a product of Colorado’s hydraulic fracturing–or fracking–boom. In April, less than a mile from Collins’ home, a Chevron-owned well “blew-out,” spewing oil, water and toxic chemicals for nearly four days.

Cleanup began right away and is ongoing, while soil and water sampling may continue for years. The Energy and Carbon Management Commission (ECMC), which regulates oil and gas drilling in Colorado, may recommend hefty fines against the company this week during a public meeting.

One environmental activist compared the spill site to Chernobyl. But Collins, and some of his neighbors, see a somewhat different picture.

He pointed out a barn and a corral that Chevron workers had repainted and scrubbed clean from oil, saying, “That's the best it's ever looked.”

Human error led to the largest spill since at least 2015

Two cascading mistakes set off the April 6 blowout, according to a Chevron report from June 10. A contractor incorrectly assembled equipment needed to install the well’s “production tree,” a bulky set of valves that regulate oil and gas when it flows up from underground.

That error then dislodged a safeguard built into the well, allowing fluids to surge to the surface. Companies use all sorts of chemicals when they drill for oil, like hydrochloric acid and chlorine, to help dissolve rock or act as a disinfectant. It’s a science. And they must report all of those chemicals to the state.

State regulators haven’t said whether they agree with Chevron’s assessment of the accident, but Greg Deranleau, deputy director of operations at ECMC, called the incident “very, very, very rare.”

In June, Chevron estimated that the well released roughly 25,000 barrels of fluids —roughly 1.05 million gallons. Most of that liquid was “produced water,” a byproduct of oil and gas operations that often contains traces of salts, chemicals and heavy metals.

But around 5,000 barrels that gushed out was oil, gas and other hydrocarbons according to the company.

The spill is the state’s largest since at least 2015, when measured by spilled water or oil, or by waste recovered during the clean-up, according to a state database analyzed by CPR News.

Local authorities established a half-mile voluntary evacuation zone as an oily mist began to fall nearby. Collins’ house was in the zone, but he stayed behind to look after his cattle. Fourteen families did evacuate though; most have now returned home.

Collins visited his brother-in-law’s farm a few days after the spill. He said he felt an oily residue as he grazed his hands through a field of alfalfa.

Contamination in soil and groundwater samples, but full extent unclear

In April, hundreds of workers descended to Galeton to begin the laborious process of cleaning up anything that may have been misted by the oily plume. That included creeks, homes, fields, barns, an elementary school and dirt roads.

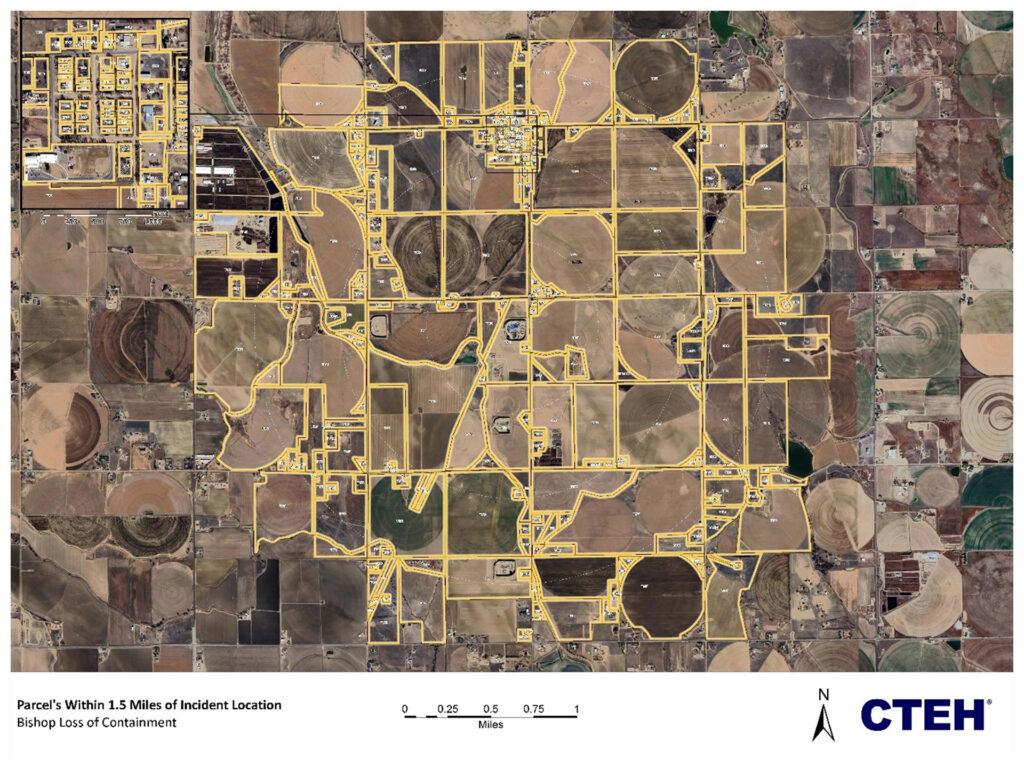

The state and Chevron divided up everything within a 1.5 mile radius of the well into around 300 unique plots. Each of those plots has its own clean-up and monitoring plan, according to Kyle Waggoner, an ECMC supervisor who’s leading the remediation for the state.

“It’s a large remediation project, there’s no doubt about that,” Waggoner said.

It’s not a simple thing to clean up. Oil spills can contain all sorts of toxic chemicals, like benzene or arsenic, that can be harmful to humans and the environment. The state sets maximum concentrations for some of those, and requires companies to test for them during clean-up. There are also federal standards set by the Environmental Protection Agency.

ECMC said its standards are the strictest in the entire country, and Chevron’s clean-up won’t be complete until its samples fall below the state’s maximum allowable thresholds. As a result, Chevron may be monitoring the well site for up to five years, though the company insists that its timeline is “a conservative estimate.”

Already, contractors paid by Chevron have taken thousands of surface water, groundwater, soil and air samples in the area around the well.

In a May 31 filing to regulators, Chevron said 20 groundwater samples and nine soil samples near the well exceeded some of the state’s chemical standards. The company hasn't submitted a summary of those results to state regulators yet, but it has submitted thousands of pages of laboratory results.

“To date, we have found a limited number of exceedances and are working to implement the necessary remediation plans,” Chevron wrote on the website it has set up about the spill. They also said the company “has not collected any [air sampling] readings that pose a threat to human health based on EPA standards.”

In May, the state’s Department of Public Health and Environment said air pollution levels during the blowout didn’t pose an immediate health risk, and that nearby drinking water systems likely weren’t affected.

But a team from Colorado State University did record temporarily elevated levels of the toxic chemical benzene in the air when the well was gushing, as far away as two miles from the site.

Olympic-sized swimming pools….full of oily waste

Oil spills create waste, and cleaning them up also generates an enormous amount of waste. Anything that’s been contaminated needs to be cleaned or removed—whether that’s water, dirt, trees or farm crops. In a single, roughly half-mile long plot near the well, Chevron said it recovered more than 122,000 barrels of liquid waste—oil and water mixed with chemicals— according to a form submitted to regulators.

That’s over five million gallons of liquid—enough to fill more than seven Olympic-sized swimming pools. Some of that waste is contaminated creek water, or oily water sopped up from nearby emergency pits.

Crews also disposed of nearly 27,000 cubic yards of waste like gravel and soil, which came from scraping off inches of contaminated topsoil from the pad and nearby fields.

“They’re leaving literally no stone unturned or unwashed,” said Collins, who’s had a front-row seat to the clean-up.

Collins said Chevron also compensated farmers to delay planting certain crops, or paid them to have alfalfa in nearby fields cut and hauled away for disposal.

Chevron did not directly answer questions about when certain farmers could plant again, or how many acres of crops were cut as part of its remediation efforts. The company said it was crafting individual plans for each property and continuing to monitor sites.

“Similar to residential properties, we are conducting soil sampling, as required, to determine if any further work is needed,” said a spokesperson in an emailed statement.

Collins said he’s watched crews scrub down buildings, repaint houses and barns, and even tackle renovations inside homes, like installing new insulation and adding new carpeting. Some efforts have even been comedic, he said.

“I watched a crew with rags and water and soap…washing the fences of a corral,” Collins said. “Well, that's really nice. But there've been no livestock in the corral for 30 years!”

Amy Hogsett, who lives nearby, said that workers even helped her wrangle some loose cattle. She’s been satisfied with the clean-up, even if the accident was unfortunate.

“I always wish they would've been faster or that it wouldn't happen at all,” she said. “But accidents happen, and machines and equipment fail.”

'Not a Disaster'

On Thursday, state regulators will provide a public update of the clean-up and discuss possible penalties and enforcement actions against Chevron.

The company did not directly answer questions about how much it’s spent on remediation, or how much money it’s paid out in claims to local residents.

Noble Energy, the Chevron subsidiary that operated the well, said two liability insurance policies were helping it cover costs. State records show those policies can cover up to $5 million in costs per incident.

Collins said that Chevron seems to have gone the extra mile during its clean-up, which he attributed partly to self-interest, so the company could stave off lawsuits. He said he felt for his neighbors who were displaced for weeks as crews rehabilitated their homes.

“It’s not a disaster,” he said of the spill. “It's actually been beneficial for some people. They've gotten stuff done that wouldn't have been done for, maybe ever. At the cost of inconvenience.”

This spill is not likely to deter future oil and gas operations in Colorado or Weld County, which has more than 15,000 active wells, many of which are close to homes, schools and communities. It does not even seem to have deterred oil and gas operations around the corner.

Chevron said it will begin the process of drilling and fracking two new wells this week, just three miles north of the spill.