Between a Republican administration that’s looking to fast-track energy projects and Democrats looking to fast-track housing projects, Chaffee County author Ben Goldfarb concedes that conservation efforts face a headwind.

Goldfarb, who’s eagerly written books on the importance of beavers to ecosystems and the role road infrastructure has played in carving up habitat, said the pendulum is swinging away from robust environmental policy.

“I think the problem with the pendulum metaphor is that once it swings in the direction of destruction of wildlife, it's hard to swing back, right? Once you lose things, they tend to be lost forever,” Goldfarb told Colorado Matters Senior Host Ryan Warner.

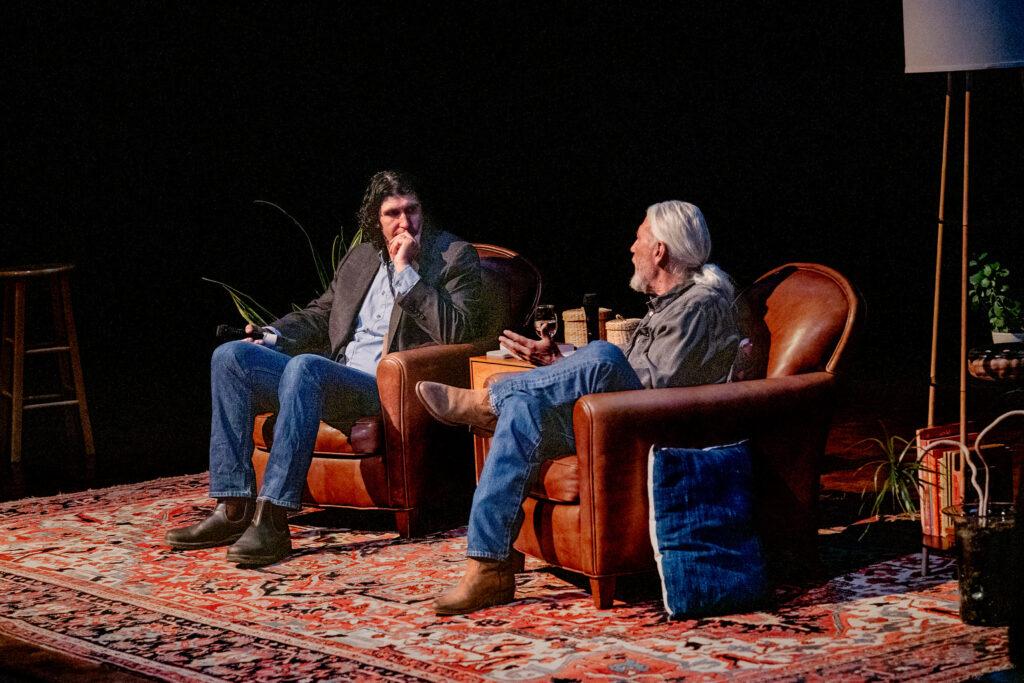

Goldfarb spoke with Warner at the Mountain Words Festival in Crested Butte. They discussed threats to conservation, reasons for optimism and his critique of an effort by some Democrats to build their way to political popularity with an abundance agenda.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ryan Warner: Your journalism considers time horizons well beyond election cycles, but I have to wonder how a second Trump administration factors into your thinking about the state of conservation today.

Ben Goldfarb: Yeah, the state of conservation today is incredibly alarming. The Trump administration has expressed its desire to sell off public lands, to reinterpret the Endangered Species Act so that wildlife doesn't require habitat, to dramatically increase oil and gas drilling in all kinds of places. So, certainly in countless ways, this is a really alarming time to care about wildlife.

Warner: I'm not asking you to bust out a crystal ball, but is this part of a pendulum? I mean, you've been a watcher of this movement for some time — of environmentalism, of conservation. Will this swing back? Does history tell us something about that?

Goldfarb: It's a great question. I think the problem with the pendulum metaphor is that once it swings in the direction of destruction of wildlife, it's hard to swing back, right? Once you lose things, they tend to be lost forever. As the great conservationist, David Brower, leader of the Sierra Club, put it: ‘We have to win forever. They only have to win once.’ Right? When you lose a species, you've lost the species.

Warner: In a recent piece, you mentioned the disappearance of 3 billion birds, 81 percent decline in migratory fish and what you call an insect apocalypse. It makes me wonder how you get up every day.

Goldfarb: Yeah. I also write a lot about hopeful stuff too. That's one of the things that keeps me going. I wrote a book about beaver restoration, for example. That's a really exciting story, right? Here's this incredible rodent who builds dams and creates ponds and wetlands that help us store water and fight wildfires and filter out pollution, and now Colorado's doing all sorts of stuff to restore beavers to our streams. So, those sorts of countervailing examples of hope and progress, those help keep me going.

Warner: Name a pro-beaver project that Colorado is engaged in. Take us somewhere.

Goldfarb: There are lots of fantastic beaver restoration projects happening in central Colorado, where I live, in Chaffee County, in South Park. In degraded streams — streams that have gotten really eroded, maybe because of overgrazing or historic mining — humans can actually go in and build our own little beaver-like dams, pound some wooden posts into the stream bed and weave some willow in there and pond some water up, and then that can entice the real beavers to come in and build their own dams and really do the job well. So those sorts of beaver-based restoration projects or beaver-inspired projects, they're happening all over the state right now, and that's a really exciting sign of progress.

Warner: Now, this is a layman's question for sure: Beavers are native, I gather, to Colorado?

Goldfarb: That's right. Yeah. They've been here, well, they've been in North America for around 8 million years, and they're more or less their modern form, and they're Colorado residents, absolutely. We nearly wiped them out during the 1800s, but they're back in force.

Warner: So this picture, you paint, for instance, in Chaffee County, where the people begin to build beaver infrastructure and then the beavers arrive. They arrive because they are nearby. Are they brought in?

Goldfarb: There is some beaver relocation happening in Colorado done by Colorado Parks and Wildlife, but most of the time, beavers just have this magical way of finding their way back into appropriate habitat. I live along the Arkansas River, and there are lots of beavers in the main stem of the Arkansas River, but some of those beavers also venture up the tributaries into the streams all over the valley. And so if you build those beaver-dam analogs, as they're called, beaver-mimicry structures in places like Four Mile Creek by Buena Vista, beavers will wander up there in the course of trying to find habitat. And, hey, there's a great series of ponds that humans have provided for them.

Warner: More recently than writing about beavers, there's the 2023 book "Crossings," which includes stories of hard-fought amphibian crossings in Florida, mountain lion bridges in California. No doubt you've considered the politics of the time, but successes do germinate outside of politics. And I wonder how you think about grassroots, community efforts to help a species across a road, for instance, versus national policy.

Goldfarb: I think one of the great things about this issue is that it can be really local. So some of the best wildlife crossings that we have in Colorado are on Highway 9 near the town of Kremmling, and there are a couple of overpasses and a number of underpasses that allow deer and elk and antelope and all kinds of critters to go back and forth over and under that highway. And that project wasn't started by some government agency, that was really the community and a local landowner basically noticing a problem, seeing lots of deer carcasses especially, and saying, “Hey, we need to do something about this,” and raising the money and the political attention to elevate that project and get those wildlife crossings built. So that's one of the cool things about this issue is, yes, there's a federal role to play in many of these projects on I-25, for example, where a new wildlife overpass is being built. Certainly, a lot of that money is federal, but it's also an issue that has a lot of grassroots support and that communities can help to push forward on their own.

Warner: You might have a better recollection of this than I do, but some time ago, I remember a story about a sensor across a road that flagged when wildlife might be crossing so that the driver could be alerted to avoid a roadkill situation. And I'm thinking about what may be lower-barrier-to-entry ways there might be beyond a full-fledged crossing or bridge for wildlife.

Goldfarb: Right, so what you're talking about are called animal detection systems, and basically the idea is, as you said, is that along the road there are cameras or radar or other sensors that basically pick up when an animal is approaching the highway. The problem with conventional animal signs — that classic yellow diamond with the leaping black deer that we've all seen — drivers habituate to those really quickly. We ignore them. Nobody sees those and hits the brakes. So we know that conventional signage doesn't really work, but if you have those kinds of real-time responsive signs that flash only when the animal's approaching the road, then drivers don't habituate to those, right? If you see the sign flashing, there's actually an animal to watch out for. So those typically reduce roadkill by around 50 percent, not quite as good as fences and a wildlife crossing, but as you say, a good option in situations where a full-fledged overpass or underpass might not be suitable.

Warner: The hot word for a while in progressive circles was ‘abundance,’ and this was largely because of a popular book from journalists, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson. They essentially advocate for more, smarter and faster building in a country that seems to have lost its infrastructure mojo. You, Ben Goldfarb, recently wrote a critique of their book and of this idea of construction-oriented liberalism. What was missing the most, do you think?

Goldfarb: Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, I have a lot of respect for those guys. I think there are lots of good ideas in their book about, for example, reducing the regulatory barriers to building new housing in already-dense urban areas. That's great. But they're taking, I would say, primarily an urban-Californian and New York-centered approach to development and construction. And if you read their book, they basically have nothing to say about wildlife, about open space. They seem mostly hostile to the idea of preserving open space, and they have very little to say about rural areas. So, in my critique, I was essentially saying, ‘Hey, it's great to densely build and develop cities, but in a place like Chaffee County where I live — and we still have lots of open space, lots of deer and elk and pronghorn migrations — let's take a second and not develop those sorts of areas as intensively. Let's think about preserving the abundance of wildlife, not only creating the abundance of housing and energy.

Warner: The idea here is the tension, I think, between density and sprawl. I'm going to read a portion of your essay, which was titled ‘An Abundance of Concrete.’

“This is a vision of America's future that has hardly a word to say about forests, oceans, freshwater, ecosystems or wild animals, about anything that isn't made by and for humans. The authors imagine a planet in which you might see a last-mile delivery drone hover like a hummingbird, but in which flesh and feather birds don't much figure.”

Where do you think the blind spot comes from? Is it an assumption that what works in Seattle works in Salida?

Goldfarb: I think that's part of it. I think part of it is urban writers writing largely for urban audiences, but I also think it's a general blindness or lack of regard for biodiversity generally, including among liberals. And a sense that those authors have, I think, that the environmental movement has become more of an obstacle in modern society than a benefit. One of the claims that they make in that book, essentially, is that we have too much regulation around building, right? We have the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act, and all kinds of codes and zoning restrictions that prevent us from creating housing and clean energy and so on, and we need to peel back those environmental regulations. And one of the points I'm making in this piece is that those environmental regulations are the reasons that we still have wild animals at all on this densely developed, urbanized planet and that to throw the baby out with the bathwater, I think would be really problematic.

Warner: Do you worry that Democrats might backburner environmentalism as they seek to find their way back to winning elections? Climate change did not seem a winning message for Kamala Harris.

Goldfarb: Yeah. One of the things that I actually worry about is climate change subsuming or consuming all other environmental concerns. And you see that in “Abundance” and in the language that a lot of liberal pundits, I would say, use around the environment as though all the environment is, is a stage against which climate change plays out. And if we could build all of the clean energy in the world, we'd essentially have solved all of our environmental problems.

I think I'm making the point in my books and in essays like this one that, again, the preservation of biodiversity and wildlife and ecosystems is one of our fundamental core values. And to just cover the planet in solar panels and wipe out everything in the process wouldn't actually be, well, it'd be solving one set of problems, but it would be creating other problems. And that, yes, certainly, of course we need more clean energy, more solar panels, more wind turbines, more transmission lines, but we need to create and site those things in a way that respects ecosystems and wildlife. And I don't see that value bubbling up in books like “Abundance.”

Warner: I mean, you write, just to quote again:

“Klein and Thompson are at root decarbonization bros, whose narrow version of environmentalism has a lot to say about solar farms and transmission lines and reactors, but little about peregrine falcons and antelope and salmon.“

Where do you think the, for lack of a better term, eco message might rest, then for Democrats or anyone interested in winning?

Goldfarb: That's a good question. It's easy to imagine Ezra Klein reading that essay if he did and saying, "Well, it's fine, but you're not going to win elections that way."

But I actually think that the preservation of wildlife tends to be really nonpartisan. In Chaffee County, again, where I live, years of community conversations and surveys revealed that the preservation of wildlife and open space was a core community value. And the county, as a result, passed this land use code that protects wildlife migration, corridors and wetlands and streams and incentivizes conservation-friendly forms of development. The county's not saying, “We're not going to build at all. We're closing this place down.” They're just saying, “Hey, we're going to invite people in and build housing, but we're going to do it in a way that respects the ecological values that we have here.”

And I think that tends to be a really nonpartisan idea. Returning to the wildlife crossings that we were talking about earlier. There's been public polling that shows that 85 percent of Colorado residents support more wildlife crossings, which is just an astronomical number. And so this idea of building and developing and creating housing, but doing it in a way that conserves nature, I think that's fundamentally a nonpartisan value.

Warner: You, in fact, invoke Chaffee County and Eagle Mountain, Utah, as communities that are making these sorts of decisions. So help me understand. There's a concerted effort, then, in these places to say, “Fine to build housing, but not here because this is a corridor?”

Goldfarb: So Eagle Mountain's a cool example, and I went there last year for a story for the magazine, High Country News, and basically, Eagle Mountain is a Salt Lake City exurb that's one of the fastest growing cities in the American West. And they have this deer migration corridor that runs through the middle of the city from one mountain range to another — right through the middle of this incredibly rapidly exploding, increasingly urban area. And so what that city has done is essentially say, “Hey, we're going to develop in a way that keeps this deer migration corridor intact. We're not going to build new housing within the area that we know the deer go. Wherever that deer migration crosses a road, we're going to put in one of those wildlife crossings so they can make that journey safely.”

They're still in the process of creating this corridor, but they're actually going to fence either side of this deer pathway. They're creating what they call a “deer luge,” essentially so that deer can just sluice through the middle of this city. I love those sorts of stories, situations where municipalities and counties and states are saying, “Yeah, okay, we're developing, but we're doing it in a way, again, that honors the natural movement of wildlife.”

Warner: Which is baked in, then, into the planning process. This is about more than thinking about sidewalks and maybe traditional planning lingo.

Goldfarb: Yeah, this is baked into their zoning code essentially. They've got a wildlife migration corridor zone, essentially, where certain types of development are restricted, other types are encouraged. Zoning is obviously not the sexiest subject in the world, but it's fundamental to conservation.

Warner: And it does, of course, become its own draw. In other words, if someone learns that there's this deer luge, that is a magnet that makes me want to go there.

Goldfarb: And that was certainly part of their rationale was “Hey, we're creating this community that is in touch with nature in some way,” and that's a draw. And I think that most people who live in Colorado, especially rural Colorado, can identify with that. Part of the reason that my wife and I moved to Chaffee County was to be close to deer and elk and antelope and all kinds of cool critters. I mean, this is, again, one of the things that makes the West special is contact with these large-scale animal migrations and movements, and I just want to see that acknowledged and respected in the discourse, essentially.