In a remote former silver mining town of fewer than 300 people, a summer repertory theater with a year-round educational mission marks 60 seasons.

“The founders would tell you it’s a miracle,” said the artistic director of Creede Repertory Theatre. Emily Van Fleet was once dubbed Colorado’s most prolific actor. Now she is in a leadership role – navigating the loss of federal arts funding.

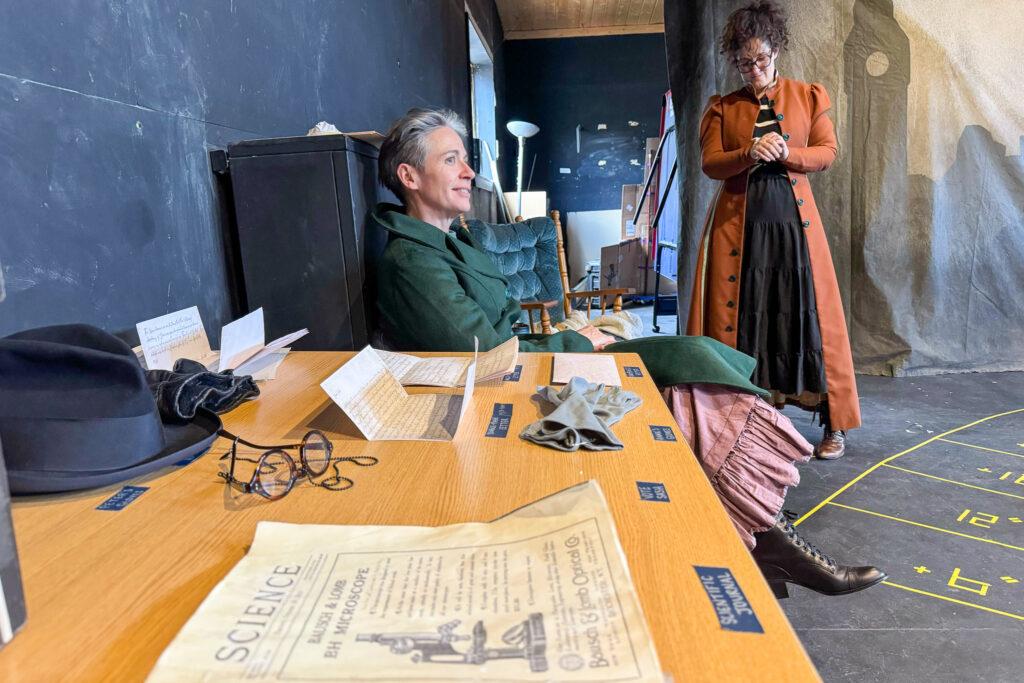

But the show must go on … or shows in this case, which are always a mix of heady plays and merrymaking musicals. This season includes, among others, the rollerskating romp “Xanadu” and the biographical “Silent Sky,” about a trailblazing woman astronomer.

Van Fleet met Colorado Matters in the Mainstage Theatre, formerly a movie house, to discuss the company’s past and its promise.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Ryan Warner: For folks who've never been to Creede, will you be as vivid as you can about what this place is like?

Emily Van Fleet: Creede, Colorado is a small old mining town at the heart of a canyon. It's a caldera. We're at the headwaters of the Rio Grande River, so there's a lot of runoff from the glacial mountains, and the birds are chirping outside and the air is crisp, and there's a lot of aspen floof going around right now and allergies are at their height.

Warner: The mouth of this canyon reminds me of curtains drawn together, and I thought, “what an appropriate thing for a town that now has a repertory festival!”

Van Fleet: Yes. The Canyon has this odd, magical energy and pull, and I think it sucks people in. And our theater is at the north end of town, our Mainstage Theatre anyway, and I think it's the perfect location to sit in that magical tension.

Warner: I'm curious how a theater company in a remote former mining town of fewer than 300 people has made it for 60 years. Emily, it is almost preposterous!

Van Fleet: Yes. The founders would tell you it's a miracle. The theater was founded in 1966 by a group of University of Kansas students who decided to help revitalize the town after the mines closed. It began with, I think, $32 and they charged a dollar a ticket and did five productions. It went well the first year and it went okay the second and they just kept doing it.

One of our core values is grit, because anybody that works here or comes here understands that doing art at 9,000 feet requires a certain amount of grit and chutzpah. You have to work a little harder for it, but that makes it all the more rewarding and that makes it all the more beautiful for our audiences, to come here for the beautiful scenery and then step into the theater and go, "Oh my gosh, I can't believe this kind of storytelling exists in this place."

Warner: It also occurs to me that grit is something that the miners who preceded you had to have.

Van Fleet: Yeah, absolutely. I guess it's a core value of our community. It's not easy living in a place this remote, at this altitude. We don't have any stoplights, we don't have a Target or a movie theater. People had to come here on purpose and stay here on purpose, and the town had to continue existing on purpose after the mines closed. It's not like an Aspen or a Telluride where you can drive through and discover it. You have to know about it and you have to come here on purpose and with purpose.

Warner: Is there something for other small communities fumbling for a new economic path to learn from what's happened here? Do you get calls like that, or is there a special sauce in this place and with those Kansas students?

Van Fleet: I think to some degree, it's a special sauce. We've done a lot of work trying to find comparables in terms of other summer theaters, other rep theaters, other rural theaters, other mountain theaters, and none of them have all of the things. I do think that if other small towns are looking for something to bring a community together, theater is the best way to do it, because it's live and it's in the moment and it encourages empathy. It's something in this digital world we live in that just is so rare. I would encourage any small rural mountain town to explore this possibility, and call me!

Warner: Do you worry you’ll draw the talent you need to fuel the festival? I know that there's housing provided, which is critical in so many rural Colorado towns, but it isn't Aspen and it's not New Hope, Pennsylvania (Bucks County Playhouse) in the New York area.

Van Fleet: That's an interesting question because if you don't know about us, and if you haven't been here, it's really hard to describe the town of Creede and the theater and what it offers. We're not just entertainment. We're very connected to our community and our local businesses and the San Luis Valley. So someone who were to come here and work here seasonally may just be looking for the next gig, and it's more than the next gig. And we try to explain to folks, we actually have an interview process, which not a lot of theaters do, especially for actors. We like to give people a really good idea of what it is they would be stepping into. And when they come here and work here, they are locals and they will be recognized on the street and they will immediately be a part of it, folded into it and woven into it.

Once people, as we like to say, “drink the Kool-Aid, the Creede Kool-Aid,” there's something that keeps pulling you back, and so we have a lot of returning company members. I get very excited to introduce new people to Creede. I'm always a little nervous. Being this isolated is not for everyone, and we do have talent that comes from big cities, New York and L.A. I’m always very pleased when I can see it in their eyes, they just get hooked.

Warner: An arts critic once called you the most prolific actor in Colorado theater– many roles here, many roles elsewhere. What stands out to you about this stage in Creede?

Van Fleet: There's nothing quite like performing on the main stage here. That's our older space. I think just because of the history, so many actors and many people are alums that I admire greatly. Mandy Patinkin graced this stage, and it feels very humbling. The Ruth Humphreys Brown Theater [down the street] is one of my favorite spaces to perform in because it's intimate. It's a black box, you can look into people's eyeballs when you're performing, it's direct-address.

Warner: Every performer, every director has war stories, shows that bombed, technical snafus. I want to take the sheen off a little here. What's one of yours?

Van Fleet: It was my 30th birthday. We were doing “Annie Get Your Gun” on the main stage. I was playing Annie Oakley. The audience was eating out of my hands the whole time. It was just the most magical experience. Curtain call happens, everybody bows. Of course, I'm the last bow, and the music swells and I come down, and the stage is on a little bit of a rake, so just a tiny bit of a slope. I come down and I'm feeling myself, and I trip and I fall flat on my face in the middle of curtain call, and the whole audience stops clapping and they gasp. I pop back up and I go, "I'm okay."

Warner: No injuries?

Van Fleet: Oh, I blew out both my knees.

Warner: Annie, get your balance.

Van Fleet: Annie, get your footing.

Warner: You lost a $20,000 federal grant that supports new works and outreach to rural communities, rural kids. Did the National Endowment for the Arts say why?

Van Fleet: My understanding is we got the same language organizations received across the country, which was, "We've decided the funding is going to be withdrawn." I'm paraphrasing, but, "Because the programs are no longer in line with the new NEA priorities." The NEA has funded us for many, many years, for our Young Audience Outreach Tour, which is a bilingual musical. It's a new musical every year that goes out to students in rural communities across the Southwest. It sees up to 40,000 students a year, and these are kids that don't get theater programs. And these plays address core curriculum.

That's not the only thing the NEA has funded in the past. Other projects include our Headwaters New Play program. We commission new plays. In the last several years, we've been focusing more on amplifying voices of the Southwest, the Latiné communities, the Indigenous communities. We also have our annual kids show, which is incredibly important to Creede local kids. It's free admission and the kids get a free three-week experience of being in a professional play that is supported by our production teams. I've never seen a model like it anywhere else, and having that funding withdrawal was a big blow.

Warner: Indeed, Creede Rep travels across the rural Southwest with these bilingual shows. Emily, can you take me to a place that stands out and tell us about young people that have built a connection with you?

Van Fleet: Before I was on staff here, I went to one of the young audience outreach tour performances in a school with 300 kids. The minute a line of dialogue in Spanish is spoken, you see many of these kids, who are English-language learners, lean in, they look at their peers, their eyes get wide. They're hooked from that moment on, and by the end, they're cheering and they're engaged and they're talking about it. They're excited and they feel seen and they feel like they belong and this story is for them, and that is hugely impactful. I can't even begin to describe it. I did a little, but it just doesn't do it justice.