Mesa Verde is one of Southwestern Colorado’s biggest attractions. About half a million people come from around the world every year to learn more about a community of ancestral Native Americans who lived in hand-made rock structures from the year 550 until 1300.

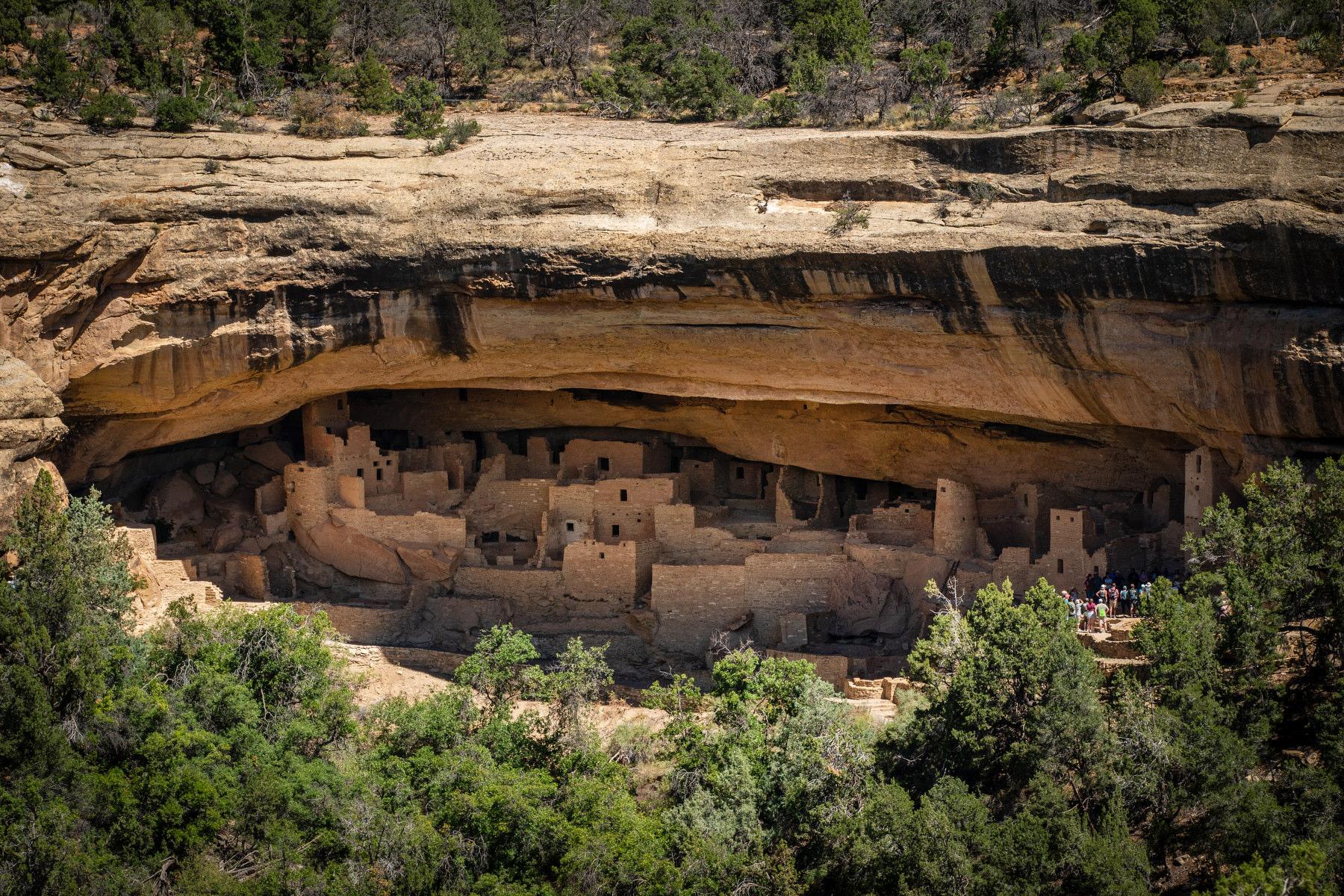

Having left the area, they left behind visual remnants that defy physics and gravity: long slabs of circular rock formations covered above by evergreens, below which remain 600 cliff dwellings, ensconced in canyon walls. Over 700 years, they built more than 4,700 architectural sites: pithouses, towers, kivas and cliff dwellings carved into sandstone and made of bricks that look handmade.

Starting in the 1270s, ancestral people migrated south to land that has become New Mexico, Arizona, and other states in the southwest. Now, members of about two dozen pueblo communities in those states claim descent from the original people from Mesa Verde.

TJ’s Tour

In recent years, voices from Native Americans with ties to its history have been brought to the forefront, including that of Thelma Jean Atsye, a retired ranger and active volunteer at the park whose voice can be heard on a 90-minute “Audio Loop Tour.” It’s one of the tours visitors can choose from when visiting the site, which has welcomed almost 37 million visitors since 1908. (During the first year, the National Park Service kept attendance data; 80 guests showed up.)

By downloading the app onto a phone that can then be played through a car stereo, guests can tune into Atsye’s calming, measured, slow-paced voice. She makes a connection between herself and the park right away in the tour:

“My name is Thelma Jean Atsye, TJ for short,” she begins, “I am Laguna Pueblo, a direct descendant of the people who used to live here. I would like our visitors to know that this is more than just a national park and a World Heritage site. This is still a living place. We still make pilgrimages back to Mesa Verde to visit the ancestors and gather strength and resilience from them.”

During the tour, guests in sun hats, bright clothes and phone cameras are ready to snap each unusual architectural feature. They can be heard speaking, gasping and exclaiming in a range of languages. Every quarter mile or so, they pull over as instructed by Atsye. They get out of their cars to see the attraction she has just described, then get back in and continue. The driving tour is one of the tamer options — another tour requires a climb up a 32-foot ladder made of logs; another involves a shimmy and squeeze through a tunnel to get to some of the cliff dwellings accessible by hand and toe-holds only.

Besides voicing the recorded audio tour, Atsye also works in the gift shop and helps new employees get familiar with Mesa Verde. Standing around five feet tall with round eyes, she is a recognizable presence with an enthusiastically raspy voice. It’s her picture in ranger gear on an oversized piece of signage in the visitor’s center.

“That I've been able to contribute to something like this, that is touching all people from all over the world and they're hearing me, they see me, they hear my voice: ‘Is that her?’ They see my name tag: ‘Hey, that's TJ!’ I'm very proud to be able to have that contemporary Pueblo person talk to someone.”

She began working on the script for the tour about eight years ago. First, she took a look at what was being said during the previous iteration of the audio tour, then she added her own spin.

”This came about in roughly around 2017. It started out as a three-, four-hour interview with two former rangers here … so just a really nonchalant interview and things,” she explained during an interview at the park gift shop, where she was taking a break from unboxing souvenir bags. “And then all I asked was a transcript once that was all done. And then, little by little, it kind of evolved into the Mesa Top Loop Audio [Tour], after revisions and editing and whatever.”

The revisions included personal touches a non-Native couldn't offer, such as: “I hope that when you hear our stories, you will begin to see these places as we do — not as ruins, but as homes. Remember, there are ancestors wherever you go; just because you don't see them doesn't mean they aren't there. If you are genuine and true and respectful, the ancestors will welcome you.”

Since TJ created this version of the audio tour, there have been about four million visitors to the park, which gets about a half-million visitors every year, a number that’s been steady over the past 10 years, dipping down below 300,000 in 2020 because of the pandemic, according to data from the National Park Service.

Departing from the past

Featuring a voice like Atyse’s is a departure from how Mesa Verde interacted with the public less than a decade ago. In the recent past, Mesa Verde was a place with white names more prominently attached. For example, the Cliff Palace portion of Mesa Verde, containing more than 100 rooms and considered the largest underground cliff dwelling in North America, was supposedly “discovered” by the Wetherill brothers while they were tracking livestock.

A 2017 press release announced a presentation focusing on them: “Over a span of many decades, the Wetherill brothers and some of their descendants passionately worked to uncover and preserve the prehistory of the Four Corners region. Harvey Leake, great-grandson of John Wetherill, will discuss the activities of his ancestors and their archaeological investigations in the area … at the Visitor and Research Center, located at the entrance of Mesa Verde National Park.”

Transition to inclusivity

The park has since transitioned to be more inclusive. Ranger Dalton K. Dorrell, a park spokesman who works with the interpretive team that promotes the park’s features to guests, spoke to CPR News in the park’s amphitheater, a quick walk from the visitor’s center. He said dancers who are descendants of the original dwellers did a performance there recently. “We had some dance demonstrations this year, from different pueblo groups, the descendant communities — Acoma, Hopi; they were both here this year.”

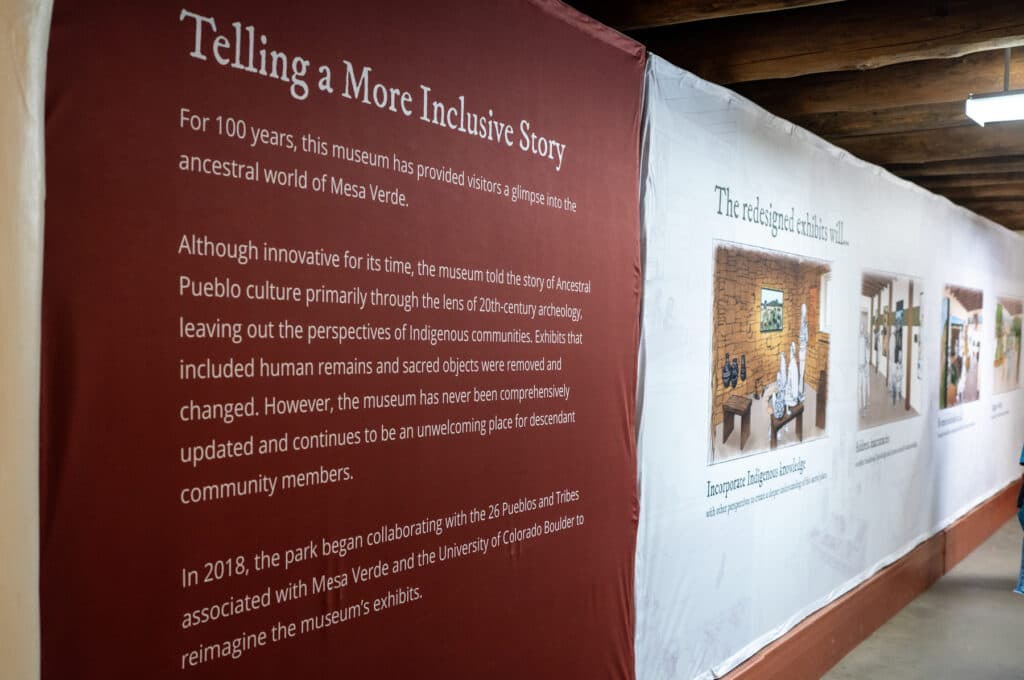

A redesign of the park’s museum inside the visitor’s center has been in the planning stages since 2019, and descendants of Mesa Verde are involved, he said.

“It was a process that was meant to take many years working, especially with tribal partners.” The museum hasn’t had an overhaul since the 1920s, he said, adding: “In this redesign, we want … multiple perspectives, especially. Bringing in those indigenous communities are key. Over the next couple of years we (are) gonna see more and more changes.”

He also said in a statement that the park is honored to have rangers from Indigenous communities play more visible roles in telling the story of Mesa Verde. “Their insight and perspective greatly enrich the experience for park visitors as well as for the park staff they work with.”

‘Footprints of Our Ancestors’

The highlighted presence of voices of Native Americans can be found not only in Atsye’s tour, but also in a 17-minute film, “Footprints of Our Ancestors,” shown repeatedly throughout the day in a small auditorium in the visitor’s center, the building that also houses the museum, set atop a hilly landing surrounded by trees and views of an endless blue sky.

Dorrell said the film, completed and uploaded last summer, is another example of an effort to include Native voices as authorities to educate visitors about the place.

The movie focuses on how Mesa Verde was a homeland, a place “where the footprints of our ancestors are protected for all the people of the world,” the narrator says. “The home has a spirit of its own; it’s not just a structure. It’s comprised of people. The home or the house is essential to family and the passing on of traditional knowledge ....”

The narrator speaks with several descendants, who, like Atsye, discuss the connections between the pueblos they are affiliated with and Mesa Verde. One interviewee from the Acoma Pueblo in New Mexico said architecture there has been informed by the structures at Mesa Verde.

The narrator explains a reason the inhabitants left: “The ancestors learned what they needed here, and it was time for the next steps in their journey. It’s not about a people who were lost, it’s about the cultural continuity that links past and present. For us, it is a sacred place.”

Another descendant in the film, a potter, makes a connection across lands: “We may have traveled hundreds of miles away from Mesa Verde, but we are still here.”

The film resonates with Atsye, who also made a voice cameo in it. Native voices telling the story of Mesa Verde gives “a different perspective from a contemporary living and breathing Pueblo person who claims direct ancestry from the ancient Pueblo people who used to live at Mesa Verde.”

The film portraying voices of other people who claim ancestry from Pueblo people doesn’t dim her shine as the sort of unofficial emissary of Mesa Verde, though. As she put it: “I'm the face and voice of Mesa Verde. Yeah, everybody knows that.”

Editor's Note: A photo caption on this story has been updated to accurately reflect the tribal affiliation of Thelma Jean Atsye.