Gone are the days of dusty boxes in police evidence rooms.

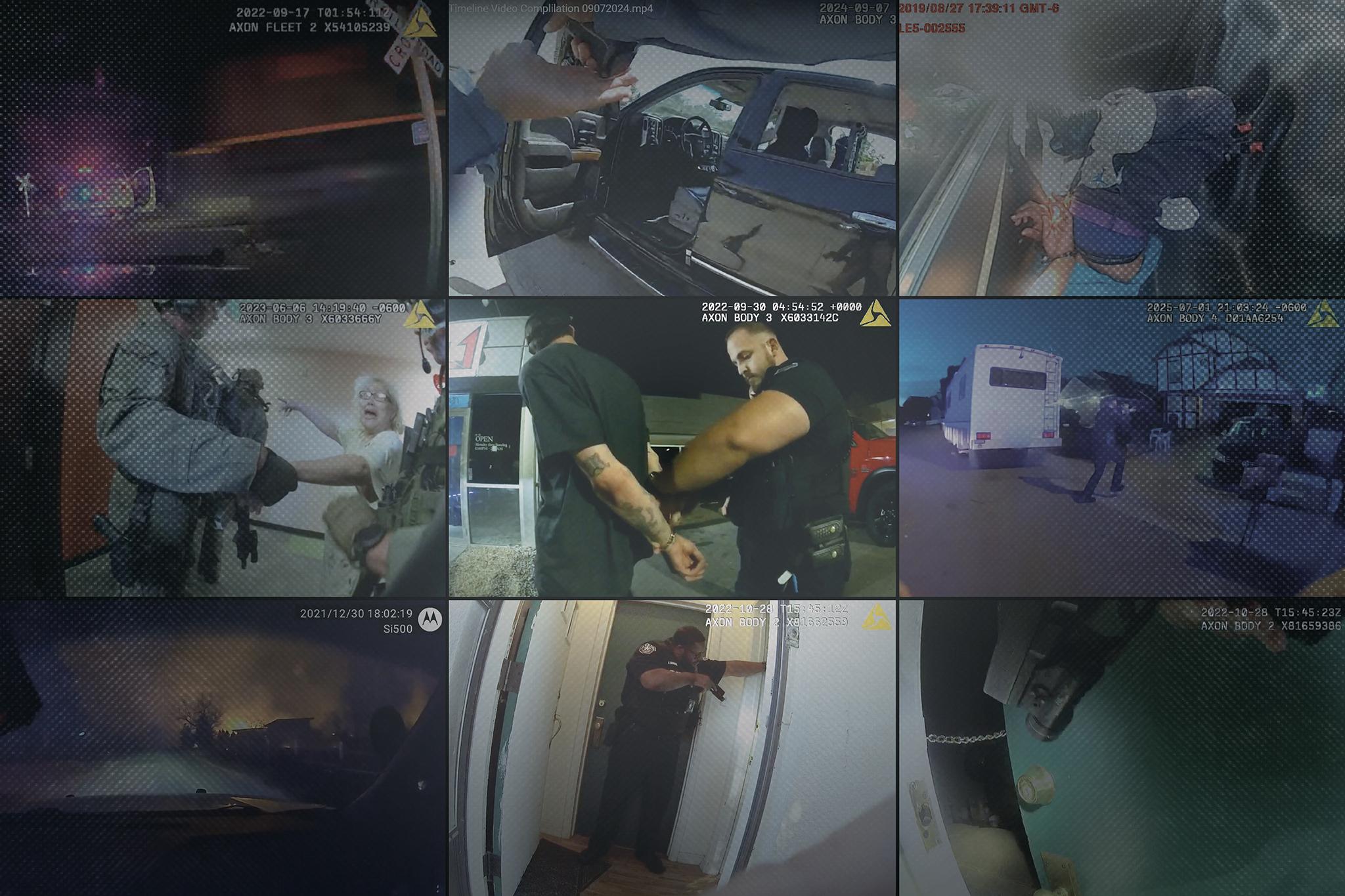

With every crime committed nowadays comes hours — sometimes hundreds of hours — of digital evidence.

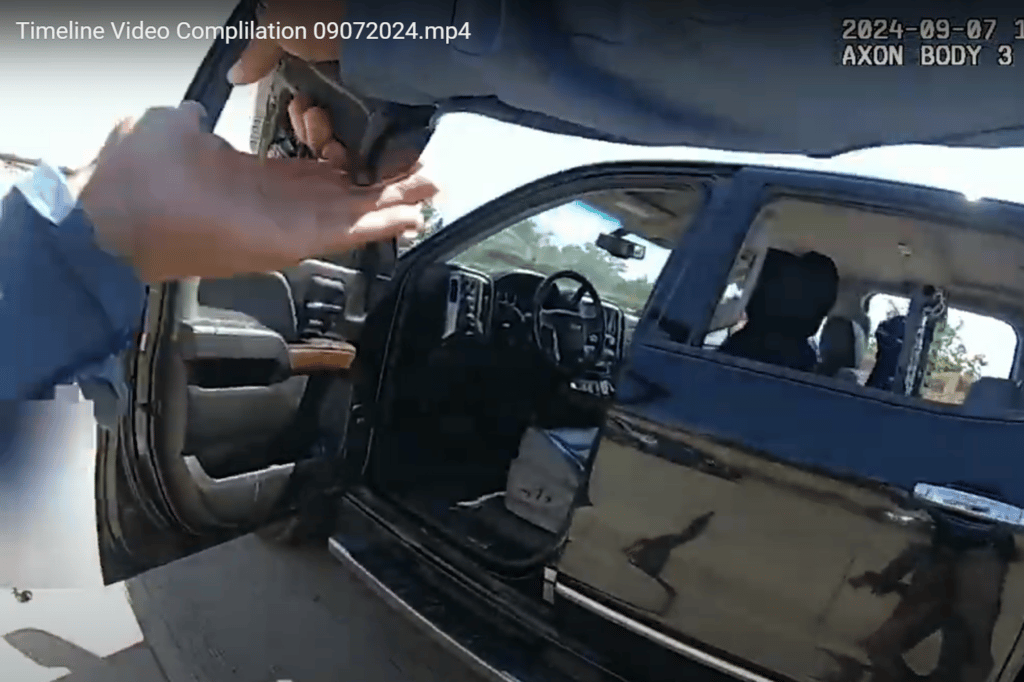

That’s body-worn cameras, Halo cameras, Flock cameras, in some cases, cell phone tower pings, digital downloads on a suspect’s cell phone, where their car was driving, video from a suspect transport to a jail and more.

Mid-grade felony cases, like an aggravated burglary, used to have three or four audio and digital recordings a decade ago. Now that same felony will yield 50-60 recordings.

And that’s not even taking into account law enforcement’s burgeoning uses of artificial intelligence.

The system has become overwhelmed.

Overwhelmed with evidence

In Denver, Chris Gray, a forensic investigator at the Denver District Attorney’s Office, said there has been a 600 percent increase in audio and video evidence in just the last five years. And that’s not just serious homicide cases — even minor misdemeanors can generate a terabyte of digital evidence. That’s one trillion bytes.

“So we’re in a minefield, and it's not necessarily one piece of the puzzle; it's all of it,” Gray said. “It's where all the data's being collected from, and then how do we manage that data? How do we properly report back on that data and what's located in the data?”

Not only are prosecutors, defense attorneys and law enforcement agencies having a hard time paying for the storage and keeping up with all of this evidence, the systems also aren’t talking to each other.

Many law enforcement agencies have increasingly pricey contracts with body-worn camera companies, like Axon, and that digital data does not always easily transfer to attorneys and others who need it. Plus, the various district attorneys around the state don’t all have premium Axon subscriptions, so they need to download the data in another way, costing hours of staff time.

“There are the haves and the have-nots in terms of funding. Some rural police departments don’t have money to store the evidence, some DA’s offices don’t have the staff to sift through it,” said Tom Raynes, head of the Colorado District Attorney’s Council.

Raynes’ office has a $3.5 million a year budget for IT infrastructure that all of the state’s prosecutors have access to. They bought and built the current system in 2015 for $3 million and have to pay $750,000 a year to keep it up, but they anticipate an increase in that contract given how big the storage is now.

“The systems are stressed,” Raynes said. “When you think of things like bandwidth and downloads and storage, all of these things, and I think the public defender shares the same problems that DA's offices do in the storage of information, terabytes, terabytes of information just growing exponentially every year.”

Defense attorneys say they’re downstream — both of the law enforcement and prosecutors. This means they often get the evidence last.

And they also say it’s costing them hundreds of hours of staff time to download the camera footage and then watch it. That could be hours of time watching a suspect in the backseat of a transport car, making sure they heard everything he said. Or hours of watching surveillance photos outside of a convenience store. And more hours tracking down geo-location data from a car or a cell phone on where a person traveled.

“Arguably, everybody doesn't have the same ability to prepare. They might be able to prepare something in two hours that now takes us 40 hours,” said James Karbach of the Colorado State Public Defender's Office. “And I'm not ascribing bad motive to anyone in that, but it's not fair. It's a problem. And when you're downstream, you can't really control the vendors or whether you have to buy something to get access to something everyone else has.”

Prosecutors agree that the workload is much harder with the explosion of digital evidence. Jefferson County District Attorney Alexis King said that her felony attorneys are handling roughly 100 cases apiece and, on average, each case has at least 4 to 6 hours of body-worn camera.

“This means each of our attorneys is responsible for reviewing 400 hours of video to ensure nothing is missing within 21 days of a case being filed,” according to a presentation she made to other district attorneys, who were discussing this problem.

King also noted that in 2022, her office handled more than 36,000 videos, adding up to 24,000 hours. In 2025, the office handled more than 67,700 videos, adding up to 41,000 hours of video evidence. A run-of-the-mill vehicular homicide case generates 362 photos, up from 79 in 2017 and up to 90 hours of body-worn camera and dashcam footage, up from zero in 2017.

A push for a better system

The legislature asked law enforcement, public defenders and state prosecutors to come together and write a report that talks about where the state is on this and where it needs to go to keep up.

There is no solution that they can agree on yet.

“It's a fundamental fairness problem in that we need prosecutors and defense lawyers and the law enforcement who produces or gathers the information to be able to make use of it with relative equity,” Karbach said. “Otherwise, people gain litigation advantage that is not premised on the facts or justice.”

Raynes agreed.

“I think where we're headed on this is coming up with a recommendation in terms of, look, we can't make this perfect, but what would be the most significant way to really take what we have to the next level?” he said. “I mean, if we're currently driving a 2010 Toyota, can we at least get to a 2025 Toyota?”