For more than a century, classes at the University of Colorado Law School have posed for a group portrait. Many of the photos — going from black-and-white gelatin prints to full-color as the years go on — line the walls of the law library, where students like Jemil Kassahun and Armania Heckenmueller often study.

“You can walk around, and you'll see photos of different classes from the eighties, the seventies, the sixties,” said Kassahun, who graduated from CU Law in 2024 and now works at the Arapahoe County District Attorney’s office.

“Sometimes when I'm bored, if I was studying and I needed a break, I'd walk around and I would start at the very beginning and just be like, ‘Okay, how many Black people?’ or ‘How many women?’” said Heckenmueller, a current law student.

“It's crazy to think some of these people — of what they had to go through,” she said. “But I didn't specifically know about any of their histories.”

Rebecca Ciota, the Systems and Digital Initiatives Librarian at the Wise Law Library, hopes to change that for students like Heckenmueller.

“My day-to-day job is mostly handling all the library systems,” Ciota told CPR News. “So any sort of catalog, any sort of backend systems.”

Since 2024, however, they have also been conducting archival research to uplift the unsung stories of former Black students.

“I was like, ‘This is going to be impossible, and I'm not going to find anything,” Ciota said. “I was stunned by how much I found.”

Ciota started their quest by looking at the school’s class portraits, trying to identify possible Black students. From there, they consulted with the CU Heritage Center, the university archives, and genealogical databases. They also parsed through yearbooks, newspaper records, and boxes of law papers.

In the Fall 2025 edition of CU Law’s alumni magazine titled ‘Amicus,' Ciota penned an article called “Uncovering What Was Always There: Black History at CU Law.”

“This project is about pursuing a whole understanding of our institution’s past, making this essential part of our shared historic tapestry visible,” Ciota writes in the article. “This research restores these individuals to the narrative of Colorado Law after, for some, more than a century of erasure.”

CU Law’s first known Black student

In total, Ciota identified more than 210 Black students who attended the law school from 1899 to 2024 and has put together biographies on six of the earliest Black students.

“There's a part of me that wishes I met all of these people,” Ciota said.

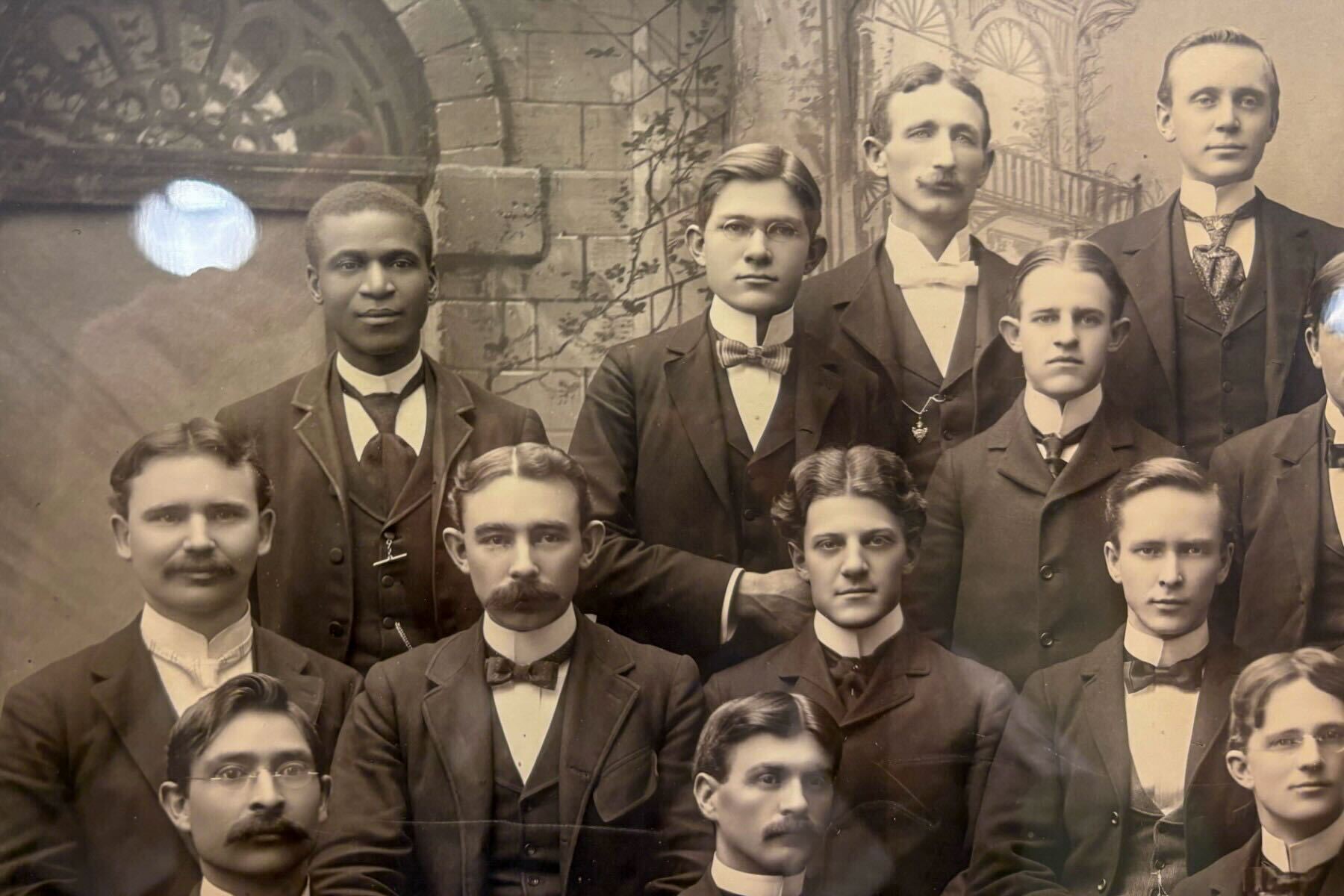

One of them is Franklin LaVeale Anderson, the school’s first known Black student. Ciota first came across Anderson in a mislabeled class portrait that hung in a dark corner of the library. The year on the photo reads 1898; it should be 1899.

Anderson stands in the top left corner at the very end of the row of students. He is the only Black face in a sea of white men, and the student next to him is obviously leaning away from Anderson.

"Franklin was born in the 1850s. He was born a free person, but at the time, Missouri was a slave-owning state," Ciota said. "He was able to get an education in Missouri, which is kind of remarkable because at the time in slave-owning states, it was usually illegal to educate slaves."

By combing through genealogical records, Ciota found that Anderson moved his family to Boulder after getting married in Minnesota and became a successful landowner.

“He buys a lot of properties and ends up opening a barbershop. He comes to the law school in 1896, and he attends for three years,” Ciota said.

CU Law only opened in 1892, so Anderson is a very early student. But he never ends up graduating, and Ciota wasn’t able to find out why.

“A lot of these students didn't get the recognition that they deserved,” Ciota said. “I can't really fix what happened in the past or in these intervening years, but I really wanted to do what I could to make these stories known.”

Connections to the present and future

Ciota said that a future step of this project is getting in contact with the descendants of CU’s first Black law students.

“I was intrigued to see Rebecca's research on Franklin Anderson because that was a name that I'd sort of, oddly enough, heard growing up to some extent,” CU Law dean Lolita Buckner Inniss told CPR. She grew up in a small, tight-knit Black community in Los Angeles, which is where Anderson died.

“I actually think he might've been someone that my grandmother and great-grandmother might've had engagement with him in his short time in LA,” she said.

As a dean, Inniss said that the current sociopolitical climate is the most challenging she has faced in her professional career. Many universities have chosen to roll back diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts in the face of President Trump’s anti-DEI crackdown.

Dean Inniss said that this project to highlight Black history “may take more courage now than it has in the past.”

“I don't think any of us saw this as a diversity project. I see this as a project of excellence,” she said.

Heckenmueller imagines what life was like for the Black students who came before her. She said this history project allows her to know the names of the faces that she has come to recognize in class portraits.

“Law school's not easy. It takes a lot out of you,” she said. “When you look at these people and their history, know everything they had to go through, it makes what you're going through seem a lot more bearable.”

She also thinks about her own impact on the students who will come after her.

“My picture is going to be up on this wall one day, and maybe in 50 years another Black girl will look at me and be like, ‘Oh wow, if she can do it, so can I,” Heckenmueller said. “I think putting the history behind it means so much in terms of the past and the future because you never know what tomorrow is going to look like.”