Published 4:05 a.m. | Updated 12:06 p.m.

Why’s Wazee Street named Wazee? Why do old downtown Denver’s streets run at an angle compared to other city streets? What’s a Barnes intersection?

We’ve read a lot of questions about the streets in Colorado’s capital through our Colorado Wonders project.

We picked a sample of some to answer with the help of the aptly titled book “Denver Streets: Names, Numbers, Locations, Logic.” The tome by local historian Phil Goodstein is responsible for pretty much all the information in this article. Find it at Denver's Central Public Library. Cheers, Phil.

Are the streets in Denver really named after concubines?

Sorry, the streets are not named for concubines. But the history of Denver’s red light district does manage to entangle itself with some street naming drama anyway.

Market Street in downtown today was the center of this so-called bordello district. It was initially called McGaa Street, after one of Denver’s founding officials. But William McGaa had a debaucherous reputation of his own, drinking and adulterating his way out of favor with the city’s elite. McGaa even named Wazee and Wewatta streets after two of his many wives, both Native American women from local tribes.

So, officials renamed his street to Holladay Street in 1866, after a well-known family at the time.

But Holladay Street soon became a hub for prostitution in the 1870s. The area was so popular that, as Denver historian Phil Goodstein writes in his book “Denver Streets”: “By the 1880s, Holladay Street had the reputation of being one of the wildest, most open, dissolute prostitution strips in the country.”

The Holladays were understandably distressed and demanded it be renamed. It became Market Street in 1887, a name that some speculate is a reference to the flourishing “business” of the area, while others claim it’s a nod to a popular open-air market nearby.

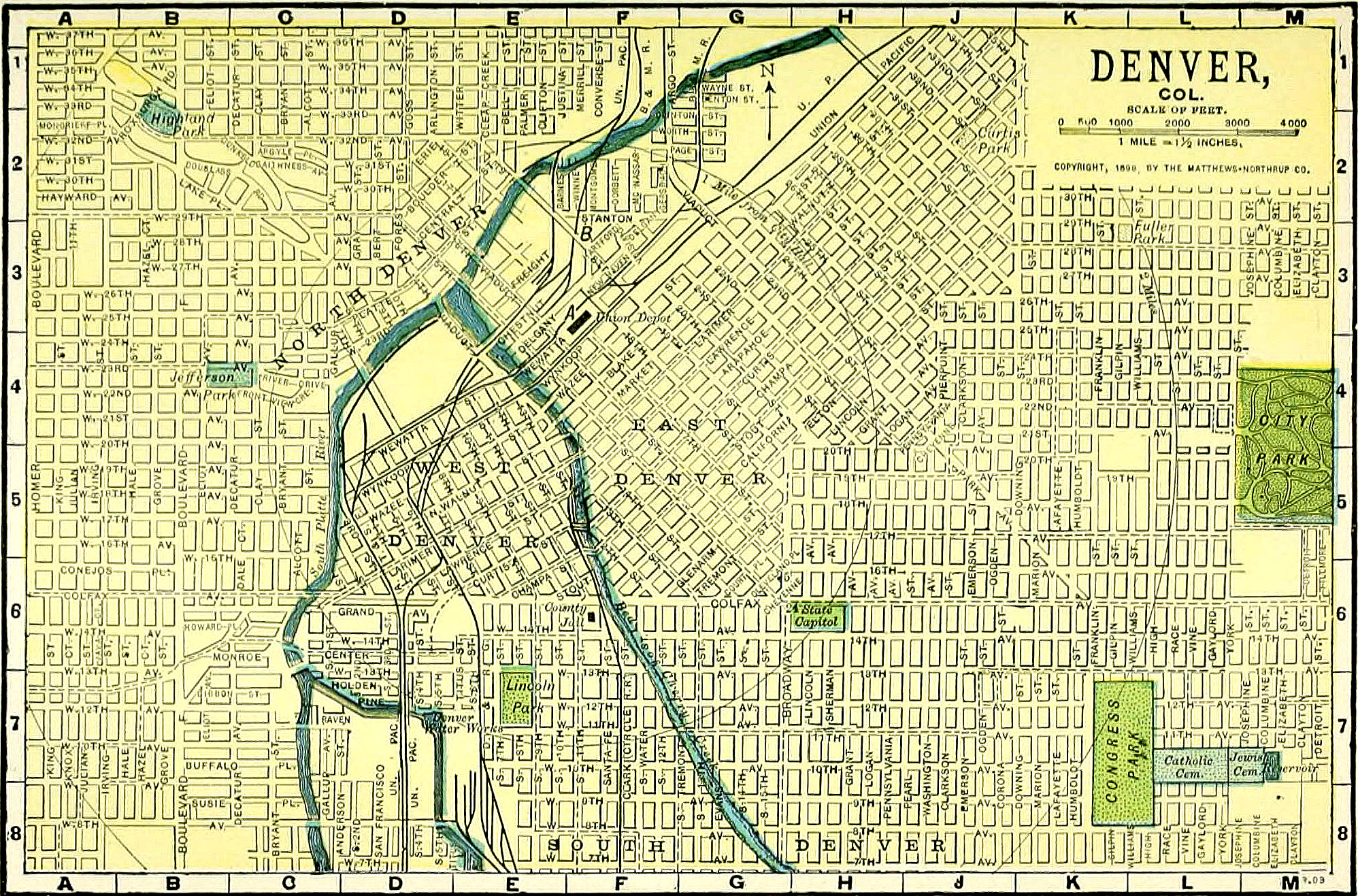

Why are the streets in downtown Denver not on the same general North-South, East-West grid as the rest of the city?

This is a tale of two young cities, Auraria and Denver City, that were both founded in 1858. Auraria lay on the west bank of the Cherry Creek and Platte River, and Denver City on the east. They would eventually combine with a third neighboring settlement, St. Charles, to form Denver.

North-South, East-West street grids were around elsewhere during that time, but especially for mining communities like Auraria and Denver City, a layout determined by nearby bodies of water was more the rage.

The diagonal streets in and around downtown Denver actually run parallel to the Cherry Creek (Auraria) and Platte River (Denver City).

It wasn’t even a decade later that street grids oriented to the cardinal directions won out. Henry C. Brown bought a 160-acre plot of land to the east of downtown that would become Capitol Hill. City planners tried to fight for the diagonal grid, but Brown worked around them and got his approval straight from the territorial legislature in 1868. Other landowners followed his lead.

Who developed the street naming system in Denver that's alphabetical, with a name first, and then something botanical? Albion/Ash, etc.?

You can thank Charles Stoll for that one. His double alphabetical remodeling of the street names running from Colorado Boulevard to Yosemite Street arrived in 1904.

The pattern is a proper noun name, ideally British, followed by the name of a tree or plant. Albion and Ash, Bellaire and Birch, Clermont and Cherry.

The switch wasn’t without resistance from those wealthy neighborhoods. When Eudora Avenue became Fir Street, residents decried the name as “too plebeian.”

Charles Stoll was really, really committed to his craft. He served as Denver’s chief draftsman for 40 years, and was badly burned when he ran into a blazing city hall to rescue engineering records in 1901.

Stoll was part of a movement led by Henry C. Maloney to bring order to Denver’s chaotic streets. Before the so-called Maloney System took hold in 1897, some streets in Denver would have as many as ten different names as they continued in one direction, or even have unique labels depending on the map. It was at best annoying, as tourists got lost and water utility customers got double-billed, and at worst deadly, as fire and police officials would also get lost.

Are the streets to the west between Inca and Zuni named alphabetically by Native American tribe?

It’s true that the naming convention from that stretch of streets borrows from Native American tribes, with a few obvious exceptions.

Again, Henry C. Maloney, who organized Denver’s street names in a logical and consistent style, was the man who came up with this set of names. However, Maloney was concerned about pronunciation. So for letters ‘G’ and ‘J,’ instead of using tribal names such as Gila Apache or Jicarilla Apache, he turned to Galapagos (for the islands) and Jason (for the hero of Greek mythology). But as we all know, anglo Denverites still plowed their own phonetical path, as seen with perennial party arguments over how to pronounce Zuni or Pecos.

At the time, many citizens protested the Native American street names. Some newspapers even said the move was “honoring ‘savages.’” For over a decade, people fought and failed to install white settler names instead.

Why are the streets of old downtown Denver and Five Points so wide?

Denver’s wide downtown streets aren’t unique. Fort Collins and Colorado Springs also feature exceptionally wide roads in their central areas, as do most cities. They allowed horse-drawn carriages and wagons to easily turn around, and for horses to be hitched to the sides without disrupting traffic.

The city also went through another kind of wide street building spree in the late 1800s and early 1900s under the rules of territorial governor John Evans and Mayor Robert Speer. The two shared a passion for constructing spacious, tree-lined parkways and boulevards, including Park Avenue and Speer Boulevard.

Why did they remove diagonal crosswalk lights and stripes from downtown Denver but never changed the timing of the traffic lights?

No fear: the traffic lights in the old Barnes intersections were changed in May 2011, not long after the streets were restriped.

If you’re like me and one of the many new transplants to Denver, here’s a run-down of what a Barnes intersection even is.

Denver popularized the “Barnes dance” intersection championed by Henry Barnes, a street commissioner for the Mile High City who introduced the pedestrian scrambles in the late 1940s. The intersections would stop traffic in all directions for a short period of time to allow pedestrians to cross the street in whatever way they wished, including diagonally.

Modern day traffic engineers today consider the crossings inefficient, including former Denver chief traffic engineer Brian Mitchell, who pulled the trigger on removing the Barnes Dance sections. The addition of the light rail, alongside the even longer waiting times for cars that it brought, were a driving reason.

“We’ve hung on to it this long because of all the nostalgia,” he told the Wall Street Journal in 2011.

Are you curious about something in the Centennial State? Ask us a question via Colorado Wonders and we’ll investigate the answer.