The Denver Broncos have been to eight Super Bowls in their storied franchise. But they say you never forget your first crush.

For fans of the 1977-1978 Broncos team, it was an Orange Crush.

“I guess it’s like the first girl you fall in love with,” says Dan Danbom, co-owner of Printed Page Bookshop in Denver. “It was very special. And it hasn’t been the same since, even though they’ve won a few Super Bowls. It was never the same feeling.”

Danbom was a season ticket holder that year, when the Broncos went to their first Super Bowl. They played the Dallas Cowboys on Jan. 15, 1978. And though they lost, that miracle season spawned a generation of die-hard Broncos fans — and ignited a civic pride in Denver.

“I would go to games and there was a Hispanic couple on one side of us, an Asian couple in front of us,” Danbom recalls. “You know, working-class people, wealthy people, and they were all just Broncos fans. And it didn’t make any difference when you got in the stadium when the Broncos were playing. They were the common denominator that made everybody excited and proud to be a Denverite.”

From Laughing Stock To Power House

The Broncos went 12-2 in 1977 before winning their first-ever playoff games on the way to Super Bowl XII in New Orleans. But Denver suffered through a lot of lean years before that magical run.

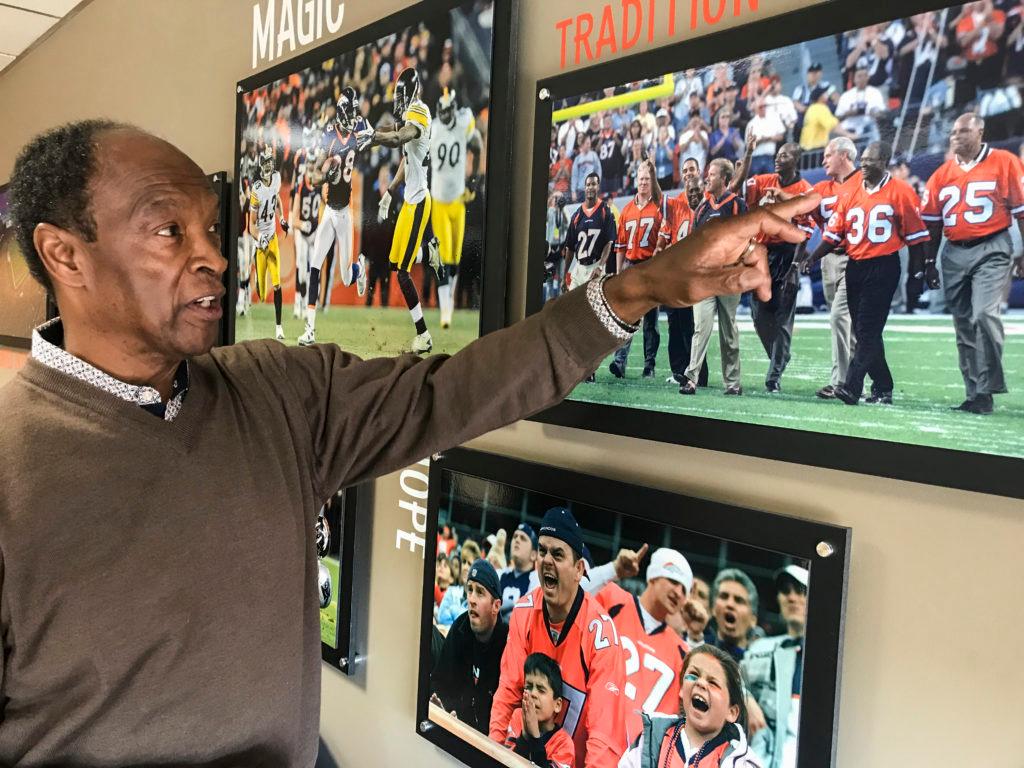

“That’s kind of putting it mildly,” said former Broncos defensive back Billy Thompson. “We were kind of like the doormats of the AFC West.”

Thompson spent his entire 13-year career in Denver. He was a three-time NFL Pro Bowl selection and is a member of the Broncos Ring of Fame. But the Broncos franchise, which launched in 1960, did not have a winning season its first 13 years.

While the Broncos languished in the AFC West behind teams like the Oakland Raiders and Kansas City Chiefs, and largely went unnoticed in the NFL, Denver itself was viewed as a cow town.

“It was flyover country,” said Dan Haley, president and CEO of the Colorado Oil and Gas Association. “Denver was very quiet. Downtown basically shut down at night. People went home after work. It was nowhere near as vibrant as it is today.”

Dick Lamm, who was governor of Colorado from 1975 to 1987, said Denver and the state of Colorado didn’t have much of a national profile at the time.

“The [National Western] Stock Show was the most popular part of [Denver’s identity], and there was a love of mountains, and a love of Colorado. I don’t mean to say it wasn’t there, but there weren’t many institutions that symbolized civic pride. But it was there and it was just waiting to be ignited.”

Danbom, a Colorado native, says Denver’s “inferiority complex” was heightened by a national media that largely ignored the Broncos.

‘Monday Night Football’ would regularly show halftime highlights of games across the league. Broncos fans “would become enraged” when they didn’t have Denver highlights, Danbom says.

But in the mid-1970s, the Broncos were finally giving people something to talk about. Denver put together a few winning seasons under coach John Ralston. He was credited with bringing in big name players to Denver around that time; defensive players like Tom Jackson, Lyle Alzado and Randy Gradishar.

Then, before the 1977 season, Denver replaced Ralston with rookie head coach Red Miller.

“The key was, [Miller] had good talent to work with when he first came in here,” said Larry Zimmer, who was a Broncos radio color commentator and a member of the Colorado Sports Hall of Fame. “Then he brought in Craig Morton as the quarterback.”

Morton had led the Dallas Cowboys to the Super Bowl seven years before joining the Broncos. At age 34, many thought he was washed-up by the time he came to Denver. But the gamble paid off that year, as Morton would finish the 1977 season as the second-rated passer in the AFC, and was named the NFL’s Comeback Player of the Year.

But it was Denver’s ferocious defense that led the charge that season; one that earned one of the most iconic nicknames in NFL history, popularized by a soda that was flying off the shelves in Denver.

“The Orange Crush,” Thompson said with a fond laugh. “I loved it.”

The Birth Of Bronco Mania

Denver’s defense suffocated teams that year. The Broncos kept winning and winning. And Bronco Mania was born.

“The contagion started out there and I caught it like everybody else,” said Lamm. “And you would have people who wouldn’t dream of spending their Sunday afternoons listening to the radio or watching the television. All of the sudden, that would be the primary thing they would put on their schedule. It converted people who never dreamed that they'd be interested in football, and now they're reading the sports pages every Sunday.

“Nobody ignored the Broncos. If you wanted to go to coffee with the guys and girls you had to now [talk] about the Broncos; it would be a faux pas if you didn’t.”

Zimmer said Mile High Stadium, the Broncos home from 1960 to 2000, had plenty of sell-out crowds before that 1977 season. But that year brought a whole new dynamic to the stadium.

“When they started winning, you began to see the all the costumes and the people with orange hair, which truthfully you didn’t see before,” Zimmer said. “And people like the Barrel Man (who was a shirtless orange barrel-wearing Bronco fan by the name of Tim McKernan) came into existence.”

Zimmer says a sea of orange would greet Broncos players at Stapleton Airport, as the team would return home from road victories. That all started when Denver beat the defending world champion Raiders in Oakland Oct. 16, 1977, to improve their record to 5-0 on the season.

“It was unbelievable,” he said. “And that continued for the rest of the year, every time the Broncos went on the road. And the crowds kept growing and growing.”

And Bronco Mania itself kept growing.

“I mean people were painting their houses orange, painting their cars orange,” Thompson recalls. “It was the most excited I had ever seen in Colorado for any sports team.”

Linebacker Randy Gradishar says the energy at the games "was over 100 percent.”

“That’s because the Broncos had never won like that before,’ he said. “Of course, Broncos fans were going crazy, and we as players were going crazy that whole year because we kept winning games, and we were feeding off the enthusiasm and craziness from the crowd.”

The crowds at Mile High Stadium were among the loudest in the NFL.

“I sat in the south stands, which were made of metal,” Danbom said. “When you would stomp your feet, there would be this vibration; you could actually feel them vibrating. And people would bring various noisemakers. There was this guy down the aisle from us who brought a collection of rubber mallets and would pound on the floor of the stadium. These guys looked like extras from ‘Braveheart.’ ”

Danbom said Broncos games were a must-see attraction, and that only one excuse would be acceptable for missing a game.

“We just assumed those people died on the way to the stadium," Danbom said.

Bronco Mania took over fans young and old. Haley was just eight years old when his parents took him to games in the north stands that year.

“My mom actually made orange and blue vests for my brother and sister,” he said. “I just remember the innocence of it all, of not ever having won before. And it was just awesome to feel a city coming together and winning those ball games.”

The Broncos season was even immortalized by “Make Those Miracles Happen,” a song performed by fullback John Keyworth.

“I still have the 45 [rpm vinyl record] down in the basement,” Haley said. “It’s on the wall. You listen to it now, it’s not the best song. But back then it sure sounded good.”

With cheesy lyrics that symbolized the Broncos struggles in their early years, the radio single became a Broncos anthem, and the hottest-selling record in Denver.

Drive To The Super Bowl

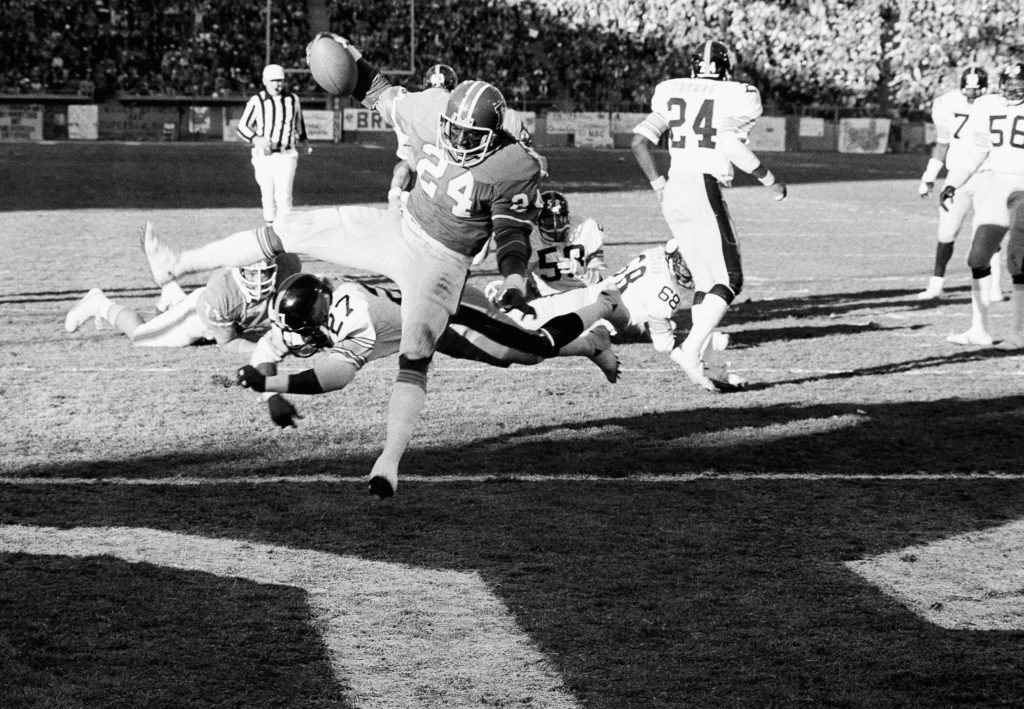

The Broncos finally won their first AFC West title that year, and on Christmas Eve 1977, they hosted their first-ever playoff game against the Pittsburgh Steelers. Pittsburgh was one of the most dominant NFL franchises of the 1970s, led by future Pro Football Hall of Famers Terry Bradshaw, Franco Harris and John Stallworth.

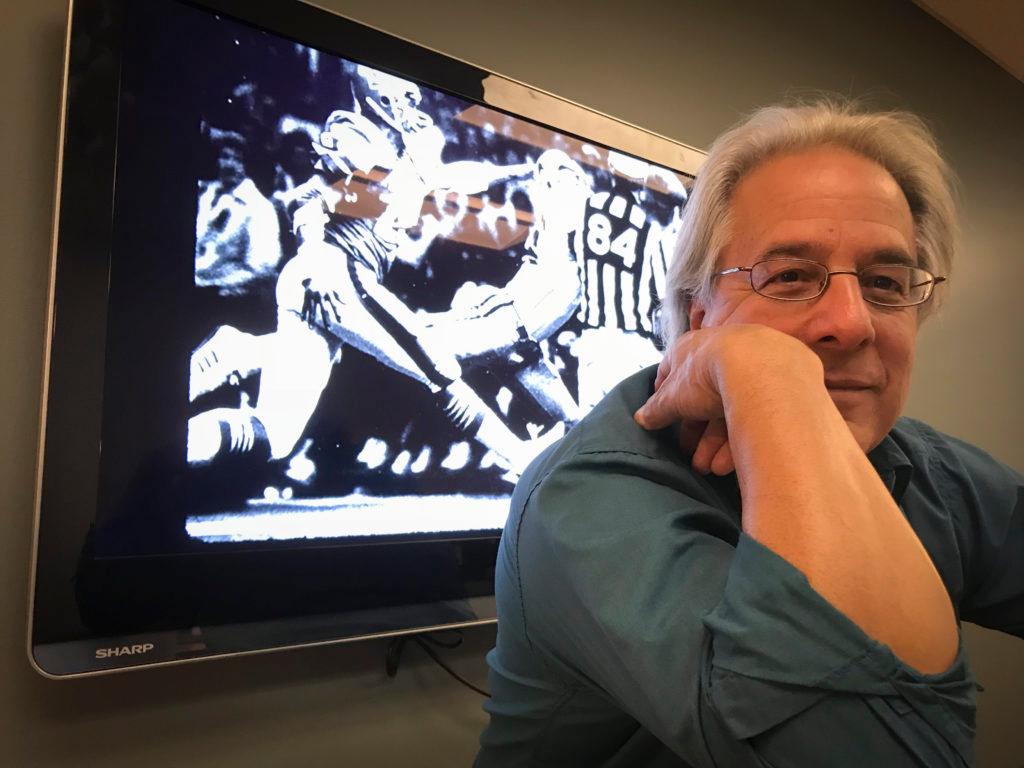

But it was the “miracle” Broncos who won the game, 34-21. Kenn Bisio was a photographer for the Denver Post, who remembers seeing the long faces of the losers inside the visitors’ locker room.

“I got to see these great players that I had always kind of grown up seeing as a kid, and they were just heartbroken,” Bisio said. “And I think that’s when I realized, ‘Oh my god, the scoreboard said that the Broncos had beaten Pittsburgh. But I thought, ‘Oh my God, they beat Pittsburgh.’ Look at how Terry Bradshaw is handling this. He's not handling it well.

“That’s when I knew this team was really something special.”

Then, on Jan. 1, 1978, Denver hosted their first-ever AFC Championship Game, against their arch-nemesis Oakland.

Bisio is from the Bay Area, and got first-hand experience of the intensity of the Broncos-Raiders rivalry when he would cover games in Oakland.

“I would come out of the Oakland tunnel with the Broncos, and got same treatment as the players did from the fans,” he said. “They would throw 9-volt batteries at us. They would dump beer out of their cups and urinate in them and throw it at you. I was bleeding from getting hit in the forehead with a battery, but I also had to change clothes because I got spilled on. I thought it was beer - but it wasn't."

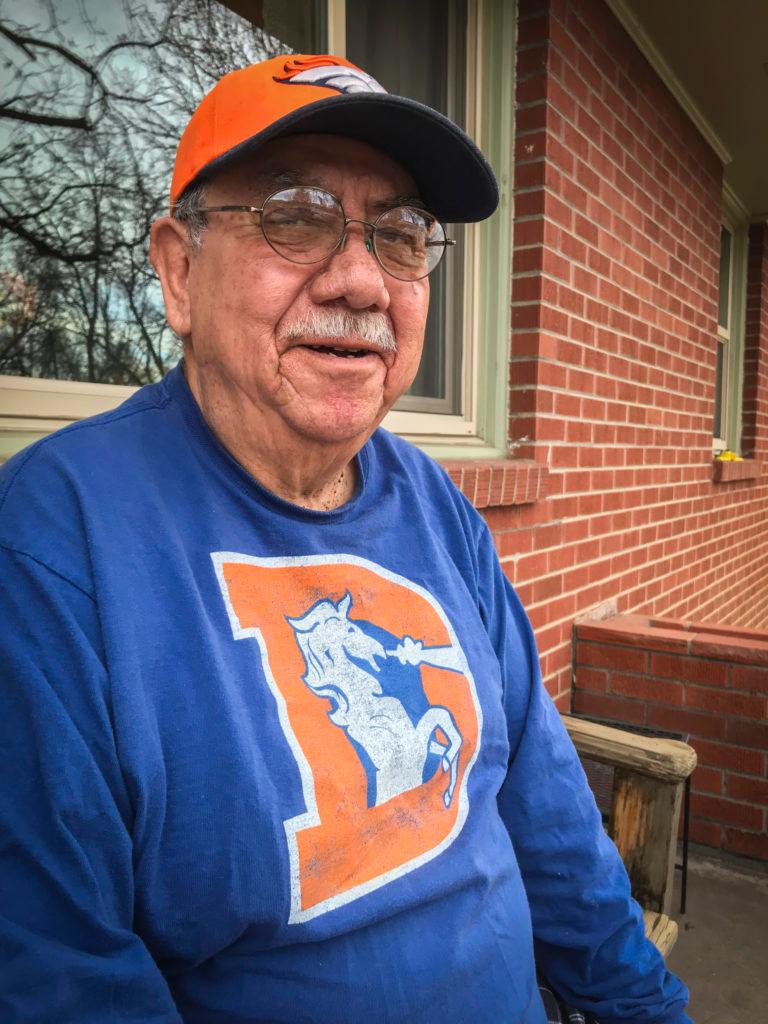

My dad, Longmont native Victor Vela Sr., said entering Mile High Stadium the day of the AFC Championship was “like entering a war zone.”

“I’ll never forget getting off that bus and walking underneath the stands to the south stands, and hearing the pounding of people’s feet that were already there – pounding and screaming,” recalled Vela, who went to every game that season.

The Broncos never trailed in that game. Led by a smothering defense that stymied Raiders quarterback Ken Stabler, and a 168-yard receiving day for Broncos wide receiver Haven Moses, the Broncos beat the Raiders 20-17.

Denver was going to the Super Bowl.

“We didn’t want to leave,” Vela said. “We wanted to stay there and enjoy every second, every moment. When the Raiders walked off that field, we were all saying a few – I don’t want to say it on this interview – but we were saying some things you don’t want your kids saying to the Raiders. And the Broncos players were just running around excited. They were hugging, and we were even hugging people we didn’t even know.”

“Broncomania erupted in downtown Denver,” Zimmer said. “They had two nights of New Year’s celebrations. One of things I remember is the goal post being carried down the field by the crowd who had rushed the field.”

Miracle Season Comes Up Short

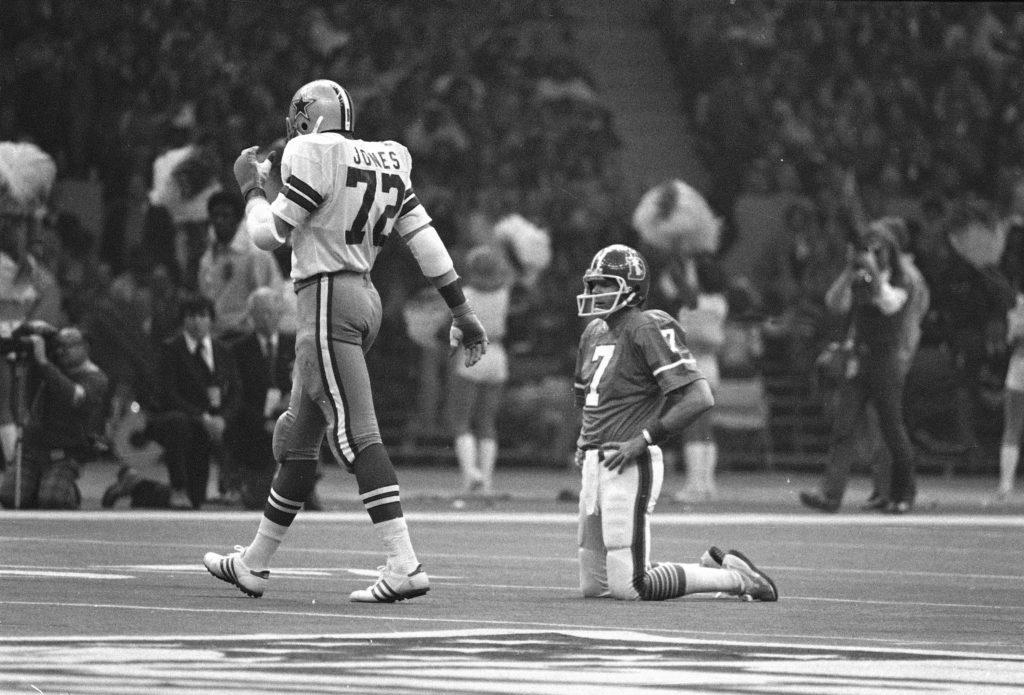

But the Broncos miracle season didn’t end the way fans and players had hoped. Denver’s defense kept them in the game, but they could not overcome eight turnovers committed by the offense. Denver lost to the Dallas Cowboys 27-10.

Dick Lamm, who went to the game in New Orleans with his son, remembers the difference between taking the airplane to the game, and the mood on the way back to Denver.

“On the way down everybody was buoyant and raucous, and there was lots of drinking on the plane,” he said. “After the loss, it was a downer. People were really depressed and I think the whole community was depressed for a week or two.”

Bisio said the Broncos may have been as nervous as he was. He was only 26 and was photographing his first Super Bowl for the Denver Post. He said his hands were shaking and that he was “scared to death” before the game. He didn’t realize until after the first quarter that he didn’t have any film in his camera.

“I was noticing a little bit different body language, a little stiffness [on the part of the Broncos players],” he said. “They didn’t have that, ‘I’m gonna win this or I’m gonna die’ look. It was like, ‘Wow, we’re here’ kind of look on their face, and they didn’t play like the Broncos. Had they played like they played anybody that season, if they just had a regular game, they would have beaten [Dallas].”

But Billy Thompson remembers a conversation he had with Broncos linebacker Tom Jackson as the game ended that took some of the sting off the loss.

“We never quit and we played hard the whole game, and as we were leaving the field, Tommy asked me ‘Did we win or lose?’ And I said, ‘What do you mean?’ Look at our fans. They gave us a standing ovation. I said, ‘Listen to that. How can we be losers with that?”

Haley said the significance of that Broncos season cannot be overstated.

“There were two moments where I felt if sports could influence culture and a community, I would say they were Jan. 1, 1978, when the Broncos beat the Oakland Raiders to win the AFC Championship, and the day John Elway came to Denver, changed Denver and Colorado in a very positive way.”

Elway guided Denver to two Super Bowl victories in the 1990s. But that miracle 1977 season lives on in the hearts and minds of everyone who experienced it.

“It made me not want to leave Colorado,” Bisio said. “I knew I was here for the long haul after that. It changed the way people lived their lives in the state of Colorado. It changed the way legislators were doing their legislation. There may have been conflict at the statehouse between Republicans and Democrats, but they both loved the Broncos.”

Editor's Note: Owing to an editing error, 45 rpm records were incorrectly identified as 45 inch records. The reference has been corrected.