What does it really mean to call an album “personal”? Pop stars and critics do it all the time to suggest that a forthcoming album will perhaps contain some barbs towards an ex or a feisty declaration of fortitude after a widely publicized faux pas. It’s often a lazy description, one that Eleanor Friedberger poked fun at with this year’s cleverly titled Personal Record (the album cover displays a freestyle swimmer in a vast blue body of water, playing on the double entendre). Given that a decent amount of superstars don’t necessarily write their own words that we perceive as autobiographical or confessional, there’s often a splash of irony to it as well.

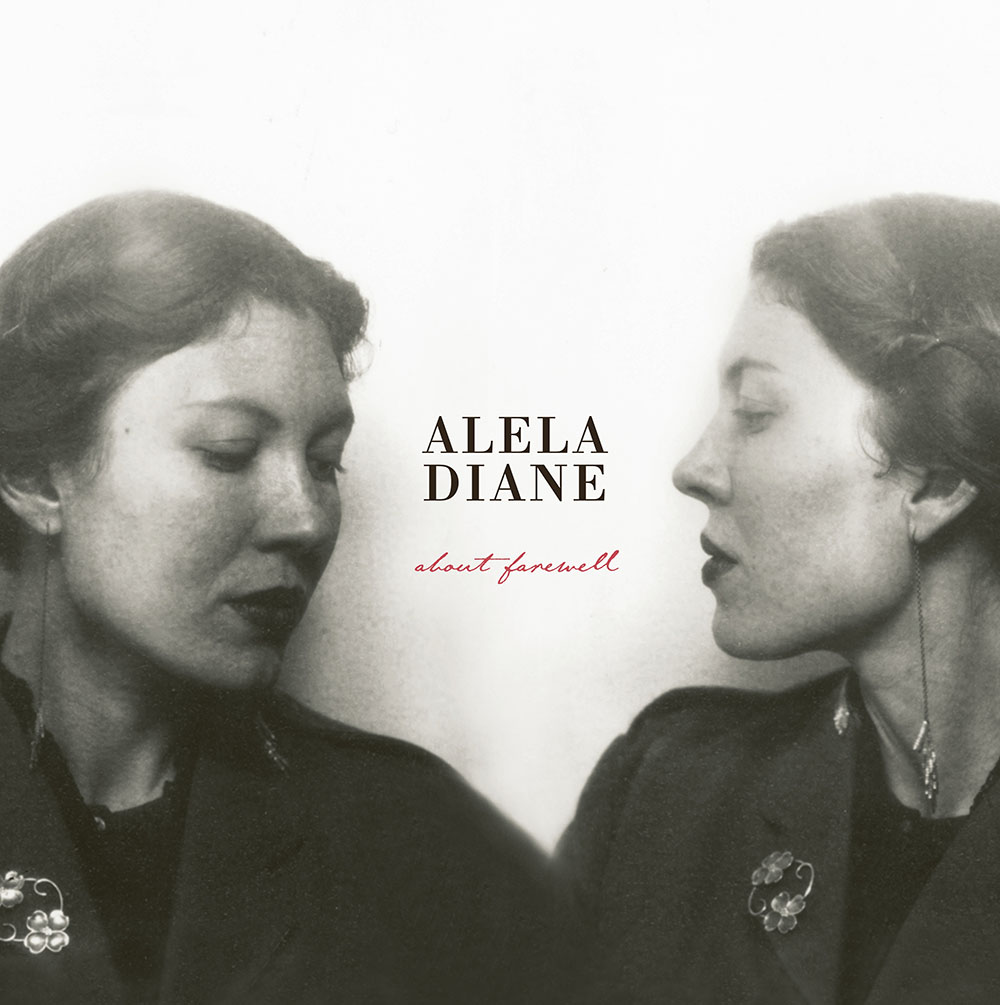

Alela Diane’s latest album, About Farewell, is about, you guessed it, saying goodbye. The Portland-based folk songstress’ full-length comes in the wake of her divorce from guitarist Tom Bevitori, who had played on and co-wrote Diane’s last album, 2011’s Alela Diane & Wild Divine. That album featured sturdy, energetic folk-rock arrangements with confident vocals from Diane, recorded at the helm of producer Scott Litt (whose resume includes work with R.E.M., Nirvana, and Patti Smith). About Farewell eschews Litt’s pop influences for ten delicately sparse, downhearted songs intended as a send-off to love. Diane’s brilliant vocals shine through as always, but with little else than acoustic guitar, occasional stings, piano, and rare percussion as backup. Opener “Colorado Blue” showcases Diane’s honed ability for complementing the colorful imagery in her lyrics with the appropriate, often haunting instrumentation. The ballad vividly recounts a bleak autumn day seamlessly accompanied by a chilling string arrangement. “Hazel Street”, another highlight, is a ghostly reenactment of a marriage proposal, a hungover August morning with ultimately dire consequences. The title track is perhaps the most poignant song on an album with no scarcity of melancholy, in which the singer mourns “the brightest lights cast the biggest shadows,/ So honey, I've got to let you go”. It’s a mature and decisive avowal, but that doesn’t make it any less heartbreaking.

Like admirable singer-songwriter breakup albums before it (Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks, Beck’s Sea Change, Nick Cave’s The Boatman’s Call), About Farewell strikes as, yes, “personal” in that it essentially captures a person, the artist behind the music, at a specific place and a particular emotional junction in time. It preserves a heartbreaking experience or series of events in a vacuum for future listens; an emotional outpouring that, given the proximity of the painful memories, ranges from bitterness to resignation to acceptance. Diane’s impressive efforts in writing all of Farewell’s tracks alone, forsaking her previous veteran producer to play a more significant role in recording and mixing, and self-releasing the album all emphasize the individuality of her work: you can practically hear the blood, sweat, and tears that went into these ten tracks through your speakers. Records like About Farewell are affecting and “personal” in that as listeners we can undergo Diane’s somber recollections of failed love with sincerity and hope that both we and the artist will come out better for the experience.