Cadence Rarden, 15, felt nervous as she stepped up to the edge of a competition ring at the Denver Stock Show Complex on a recent Friday. In her hand, she held a leash that kept one of her family’s 5-foot-tall alpacas in line.

The grayish-brown animal, named Aladar, quietly followed alongside. The two were up against other gray alpacas.

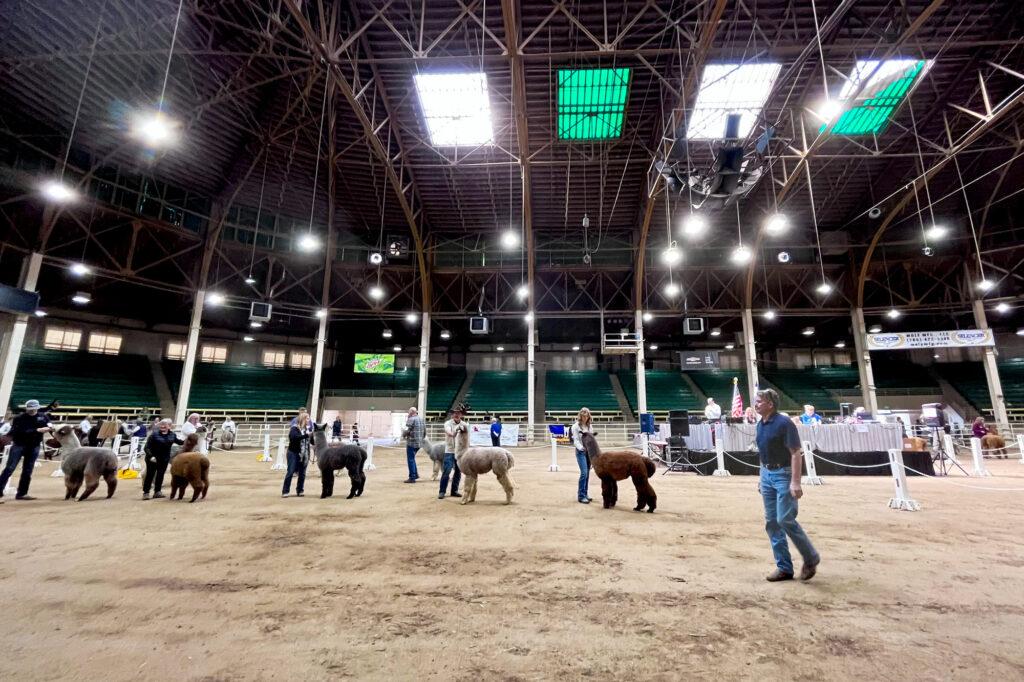

When a judge motioned for Rarden to move forward, she led him in a circle before stopping in a line of four other animals and their handlers.

“He has a really great presence about him,” the judge said to her before poking and prodding his frame, looking for any imperfections. “He’s nice and level and we’ve got a good uniformity of fleece.”

The judge backed away and took one last look at the group before pointing to Rarden and Aladar and handing them a small blue ribbon. The duo won first place in the division for gray males during the Great Western Alpaca Show, the region’s largest annual competition for the specialty livestock.

“I’m so relieved and really happy for him,” Rarden said as she walked out of the ring with a smile on her face. “Like the judge said, he’s a complete package.”

Rarden was one of about 500 breeders who competed in the show, the first regular event of its kind since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. In it, alpacas are sorted into separate divisions by gender, age, species and color of fleece. Winners go head-to-head in championship rounds later in the day.

The stakes are high for many breeders. Top prize-winning animals earn thousands of dollars more and it helps them stand out in this small, but competitive industry.

While the show carried weight, it was mostly a chance for farmers to show off their best animals and network among the state's sizable community.

“I love the people and the atmosphere is just amazing,” said Rarden, whose family owns an alpaca farm in Livermore, just north of Fort Collins. “Seeing the quality of the alpacas is also really cool.”

A bumpy road for some

The show has been around since the mid-90’s, when alpaca farming first took off across the United States.

Back then, thousands of investors poured their money into the animals, hoping their fleece would gain traction in the country’s textile industry. Colorado’s arid climate mimicked that of the animals’ native habitat of the Andes Mountains in South America, which made the state an ideal place to raise them.

At their peak in the early 2000s, a single alpaca sold for over $26,000.

But the hype was mostly speculative, due to comparatively low consumer demand and a lack of fleece processing capacity. Multiple studies show the supply-demand imbalance caused the alpaca bubble to burst sometime around 2005.

Prices have come down since then, and the number of farmers in the business has dwindled. But there’s still money in it, said Sharon Loner, a retired breeder who now volunteers as a scorekeeper at GWAS.

“A lot of people were in it for the wrong reasons,” Loner said. “Now more breeders are in it for the fiber and breeding programs.”

Alpaca fleece is mostly used as a specialty textile product. Small clothing producers are the biggest buyers, making hats, scarves, gloves and other high-cost accessory items. High-quality fleece on Huacas, the more common subspecies of alpaca, can go for around $200 per pound.

Like other industries impacted by the pandemic, consumer demand dropped sharply during 2020 and most of 2021, said Rebecca Vin, a breeder from Washington who traveled to Denver for this year’s GWAS show.

“We don’t even count COVID,” Vin said. “Now it’s back up again. It’s really easy to sell animals and fleece again, which is really nice.”

Today, there are roughly 10,000 alpacas in Colorado, according to the latest data from the Colorado Department of Agriculture census of the species conducted in 2017. That number is extremely small compared to other livestock, such as cattle, which are in the millions.

“It hasn't died out like we've seen with other specialty livestock,” said Loner, the retired breeder. “And by that I'm talking about maybe the emus and the ostriches, you know, they were going gangbusters three years ago and now not so much, but these guys are hanging in there.”

Many farmers are retirees or hobbyists. The animals are relatively docile and lower maintenance, which makes them easier to care for than other livestock, Loner said.

“They have this calming effect and I think that's what draws a lot of people to raising them,” she said. “Older folks can handle these guys.”

Judging comes down to fleece and frame

At GWAS, alpacas are split into two main competitions: halter shows and walking fleece. Judges are often breeders themselves. They go through a certification process with various industry groups.

In walking fleece, animals are judged solely on their coats. Quality is determined by the uniformity of their micron strands and even color across their body.

Halter shows take a more holistic view of the animals. Fleece is a factor in judging, but so are teeth, legs, head size and feet.

“All four feet need to be firmly on the ground,” Loner said. “They can have weak ankles, which is a defect.”

As breeders lead their animals into the ring, judges observe how each alpaca walks and behaves. That’s half the process. Then, they get their hands on them, looking at the shoulder, stomach, hips and more.

“They’re also spreading the fleece and looking for abnormalities in color,” Loner said. “In a solid class, say a pure white, if there's a spot, like a black spot, you get dinged for that lack of uniformity of color.”

Ribbons are given for first, second and third place in each division. Judges often give brief remarks to spectators following each round. Then those winners go head-to-head for a championship.

A champion in the making

Rarden was the youngest of this year’s finalists.

“I have a few friends that are in the business too from their parents, but there's not a lot of younger people doing it,” she said.

Rarden has done it her whole life though. She hopes to take over her family’s farm one day and grow the business so alpaca fleece is used as much as sheep's wool.

Her grandma, Sharon Milligan, who also showed alpacas at GWAS, agreed.

“With her energy that she has, I'm pushing her that way,” she said. “Believe me.”

Rarden and Aladar were against five other alpacas in the championship round. The judge went animal to animal, before handing a big blue banner with gold tassels to the teen and her animal, congratulating the pair.

Rarden shook hands with the competitors before leaving the ring. She said never gets tired of working with the alpacas.

“They're just so sweet and they're just so cute and it’s just something that draws you to them and they're just amazing things to have,” she said.

Aladar was rewarded with a fresh bale of hay to chew and rest until it was time to head back home.