On a long, straight road across the rolling grasslands of New Mexico, there’s an island of trees shading low buildings: the village of Roy.

The tiny city’s blocks are tidy but half-vacant, looking as if the community is slowly evaporating in the High Plains sun. But a cluster of businesses remain open at the entrance to town — a one-pump gas station, a coffee shop and a general store.

Inside, the husband-and-wife proprietors stood greeting regulars in the comfortably dim light on a summer afternoon.

“We run Gabrielle’s Convenience Store, and I’m also the mayor here in Roy,” said Edward DeHerrera by way of introduction.

I’d driven to this spot, some 300 miles south of Denver, to see Harding County, N.M.’s little-known natural heritage. It’s home to fireflies. The luminous bugs are a staple of summertime in the eastern U.S., but they’re so elusive in the arid West that people can go a lifetime without seeing one — or even knowing they’re here.

In Roy, the lightning bug is not exactly the town mascot — that would be a cow or a diamondback rattlesnake, DiHerrera joked — but it’s not a secret either. When I asked, the mayor thought back to nostalgic memories of summer nights along the banks of the Canadian River, before the drought.

“When I was younger, it used to rain so much. It was beautiful, tall grass,” he recalled. “You’d be out there with your campfire, and they’d be out there along the river and moving around.”

DiHerrera hadn’t been down to see the bugs in years, busy as he is raising a family and trying to revive his hometown’s prospects. And he wasn’t sure what I would find by the river down in the canyon, where he said decades of low rainfall finally resulted in a completely dry riverbed earlier this summer.

The river “will stop running once in a while, but I’ve never seen it dry. And this year it was dry,” he said.

A little-known species

Outside the convenience store, a Honda CR-V was pulling up, with a woman named Anna Walker behind the wheel. She’s a researcher with the New Mexico BioPark Society who has been trying to learn all she can about the state’s far-flung firefly populations.

“Sorry I’m so late, it was a crazy day today!” she exclaimed.

She was about 20 minutes behind schedule because her week had been jammed with media interviews about a different insect. In her role as a “species survival officer,” she has been working on a project that recently declared the monarch butterfly as “redlisted” — a designation from the International Union for Conservation of Nature — that drew national media attention.

But it’s the elusive Western fireflies that have become an obsession for Walker over the years, leading her on quests to lonely wilderness sites across New Mexico, Colorado and beyond. She’s part of a grassroots campaign by scientists and ordinary outdoors-folk across the West to find and document the bugs.

Western fireflies have only occasionally been studied by scientists, who know little about their distribution or even what species have survived in far-flung pockets. What is certain is that the insects need water, which means they’re likely imperiled by the decades-long drought that has wracked the region.

When I told Walker about the river drying up, with even the puddles scorched away for a time before the monsoon started, she grew worried about the canyon’s lightning bugs.

“Wow, that’s pretty scary,” she said before we departed. “Well, I’m curious to get down there now.”

We drove out of town, eventually turning onto a dirt road. A gradual dip in the grasslands suddenly became a precipitous drop, as the road wound down a thousand feet into a broad, grassy canyon rimmed with red rock and evergreens.

“Driving in, I was starting to get just a little bit giddy,” Walker said as we paused at an overlook. “This is just one of my favorite places in New Mexico, and in the world, really.”

At the canyon’s bottom, we found the river slow and muddy, but at least it was running again. There was no one else around as we pitched our tents among the shrubs and low locust trees, then sat down to talk.

This was Walker’s third visit to the site, one of 22 sites she’s cataloged so far. It’s a mission she began just a few years ago, when she joined a project to assess the threats facing more than 130 firefly species across North America.

The research was focused back East, where fireflies are common. She’d only seen fireflies a couple times before, and she couldn’t help but feel left out of the excitement in New Mexico.

“I kept thinking to myself, man I wish we had fireflies in the western United States, because like most people, I thought that we didn’t,” said Walker, who’s from Colorado Springs and attended CU Boulder.

But as she trawled through databases of entomologic observations and specimen records, she kept spotting scattered reports that contradicted that assumption, and piqued her curiosity.

“Every once in a while I’d find a really old specimen from New Mexico or from Colorado, or I'd hear a report that there used to be fireflies in Denver, along Cherry Creek, or in Boulder,” she said.

Walker soon learned that other researchers were on the same mission — most notably, the Utah Firefly Project, which has logged hundreds of sites since 2014. But sightings in New Mexico in particular were rare. The scientifically recorded observations had mostly happened decades ago. And when Walker started visiting sites in search of fireflies, she had little luck.

Growing up on the East Coast, I could see fireflies just by walking down the block in the summer. I’d even seen swarms in the Southeast flashing in unison, seemingly by the thousands. But setting out on your own to find a firefly in the sprawling plains and mountains of the West is unlikely to yield many results.

“You have to be in the right place, the right time of year, the right time of night,” Walker said. “So, a lot of people miss them, a lot of people, even if they’re right on top of them, will never see them.”

The historical record gave her little to go on. A sample might say it was collected in July 1903, but was it early July or late July? Were the records mislabeled? Had the fireflies survived at all?

Eventually, Walker found a solution: crowdsourcing. Walker logged back onto Facebook for the first time in years and started posting to groups focused on critters and the outdoors.

“That was just my only way of reaching a large number of people in random parts of New Mexico,” she laughed.

By enlisting thousands of ordinary people, she soon turned up dozens of leads. Of course, she also heard from some old-timers who insisted that fireflies don’t exist out here.

This kind of distributed, citizen-powered science is perfectly suited for entomology. Across the world, scientists documenting the troubling declines of insect populations have relied on legions of citizen volunteers. After all, there are many more bugs than entomologists.

And citizen science has long played a role in the study of fireflies in particular. Scientists didn’t know that synchronous fireflies existed outside Southeast Asia until Lynn Frierson Faust invited researchers to a family cabin. Faust has since become an expert and written a field guide that Anna Walker brings on her research trips.

Eventually, the members of a critter-focused Facebook group gave Walker a breakthrough hint. They pointed her to this very canyon, where she finally spotted her first Western firefly display three years ago.

“Just past sunset, I saw a little spark, and then suddenly I saw another little spark, and another one,” she said. “And suddenly, they came to life.”

Walker’s now coordinating her work with researchers in other states and helping to turn the Utah Firefly Project into the Western Firefly Project, which currently covers Utah, New Mexico, Wyoming, Idaho, Nevada and Colorado

The goal is to return “year after year, ideally at peak flight,” to gather data on a range of questions, including whether climate change-driven drought and other factors are driving a decline.

But it’s not just about data. Walker had told me earlier that part of the draw of ecology came in the “intimacy” of visiting a landscape again and again — to get to know one place through its changes.

‘It’s just magical’

As the light faded, Walker took out a big bug net, a tiny temperature logger and her smartphone, and set up a camp chair near the riverbank.

“I’m kind of worried there are not going to be very many of them this year,” she said quietly. “It’s so dry.”

As we waited, the sunlight bled off the canyon walls and a chorus of crickets rose up. I’d been thinking about this moment since I’d first heard of the Western Firefly Project last summer.

But before the dark fully set in, I wanted to ask: Why is Walker doing this? Why travel so far to document something so small in the face of such dramatic changes? Why do fireflies matter?

“I never really had to ask myself that, because I know that it matters,” Walker replied. But she acknowledged that the firefly doesn’t exactly fit the reasons we learn in biology class that a species might be important.

The lightning bug “tastes really bad and doesn’t have a lot of predators. It’s not necessarily feeding a lot of other wildlife. It’s not a pollinator so it’s not helping plants to reproduce,” she said.

But she told me every species has a role in an ecosystem. For example, firefly larvae eat snails, worms and slugs. She added that it’s not too late to slow changes in individual ecosystems. And she explained that fireflies are a visible reminder of how drought can change a place.

“Last year, it was really lush,” Walker said as we watched the underbrush for flashes. “When it’s like that, it’s just magical — they’re everywhere.”

Just at that moment, she spotted the first one. “Ooh, I think I saw one!” she said with a start. “Just a single flash.”

A minute later, I also spotted a yellow-green arc through the bushes. Over the following minutes, a few dozen more emerged and spread out from the underbrush. We could see individuals tracing big hooks through the air and zipping along the river, each light strobing every five or six seconds.

The males flew overhead, while females matched their pattern from the brush, hoping to draw down a mate.

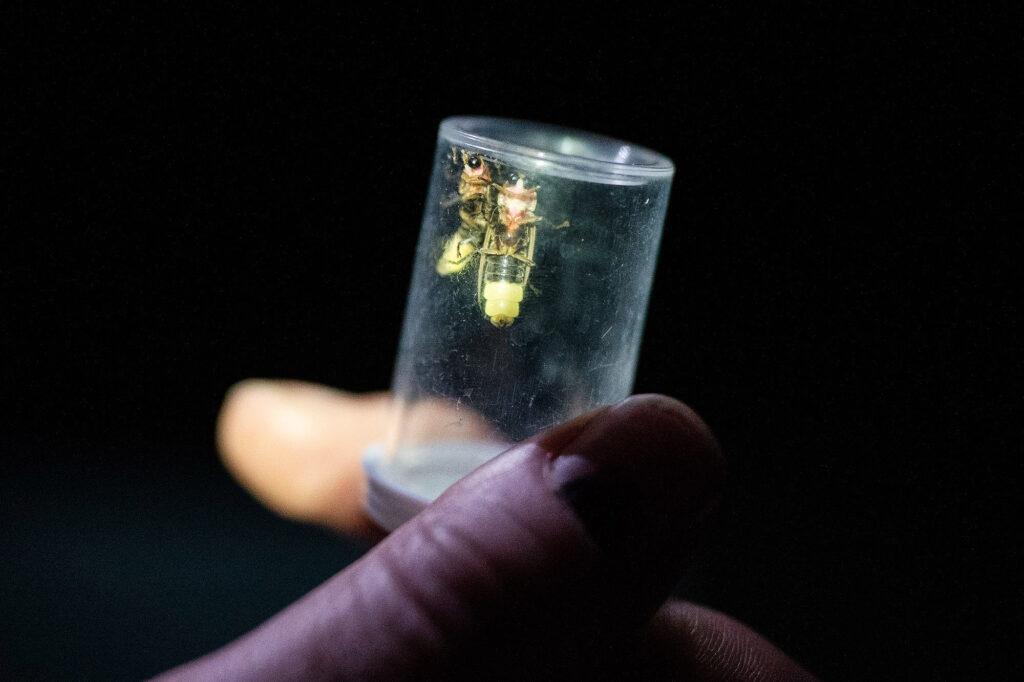

Walker counted flash patterns and picked out other little details, hoping the whole time to build on her theories about the site. She had sent samples of this population out for genetic sequencing, but the results weren’t back yet. The canyon bugs resemble the Big Dipper variety that’s common out East, but there are significant differences in the males’ body type. Walker also suspected that a second species may be found in the canyon, but she hadn’t been able to collect one yet.

“It’s just so hard to tell sometimes what species you’ve got at a site,” she said.

Long ago, when the West was a wetter place, fireflies may have been far more common. But Walker and other scientists think that most died out as the land dried over millennia, leaving scattered populations in stranded spots.

These populations have likely diverged from their Eastern cousins as they’ve adapted to drought. Perhaps they can even go dormant during a dry year, skipping a whole summer of light shows, Walker theorized.

But “whether they can withstand increasing severity and frequency of drought under climate change,” she told me, “is a whole ‘nother question.”

And there are other climate-driven threats to fireflies; earlier this year, the Cerro Pelado fire had scuttled my hopes of joining Walker to look for a population in the Jemez Mountains.

This evening, Walker estimated, there were a couple hundred fireflies on display at our site in the canyon, less than half the number during last year’s wetter season. Seeing the sparse lights drove home the reality of long-term drought. But I found beauty in it, too.

“Every once in a while, when it’s clear, man, they’re bright,” Walker said.

We could spot individual lanterns flaring from hundreds of feet away, their lonely lights somehow brighter against the endless dark that had fallen down the canyon. It felt more wondrous for how delicate it was, fairy lights rising from the parched earth.

But the display doesn’t last long. Soon, there were just a few bugs still blinking along the river, leaving us with the crickets and the Milky Way.

“And then there was darkness, and they all went silent,” the scientist whispered with a laugh.

Early the next day, we packed up our tents and prepared to drive out of the canyon. Walker was headed toward her next site, where she hoped to find a species that hasn't been recorded in New Mexico for a century.

“Slowly, slowly, little by little, you learn a little bit more every time,” she said.

For now, a night on the Canadian River had added one more observation to her record of a changing landscape and its inhabitants.