“You didn’t ask us the question everyone asks,” said Erin Manzitto-Tripp. “What do lichen do?”

Manzitto-Tripp is an associate professor at the University of Colorado Boulder in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. She’s also the curator of botany at the school’s Museum of Natural History. But, first and foremost, she’s a lichenologist.

“What do squirrels do?” she posited. “What do humans do? Lichens do a lot of things.”

Together with Ph.D. candidates Jacob Watts and Seth Raynor, Manzitto-Tripp is leading the charge to document Colorado’s vast lichen population.

“The ratio is one lichenologist for 1000 botanists on earth,” she said. “That just shows you what an enormous task we have.”

She’s part of a team of three — the only three lichenologists in the state of Colorado. Together, they’re hiking hill and dale to catalog as many of the state’s species as possible.

When her team began its research, there were approximately 700 known lichen species in Colorado. When their research is complete, they hope to have a log of over 2,000.

This summer, they identified three “charismatic” lichens and named them in honor of the Indigo Girls.

What is a lichen?

Jacob Watts came to CU Boulder to study plants.

“Like many people in the United States, I didn't really know what lichens were,” he said.

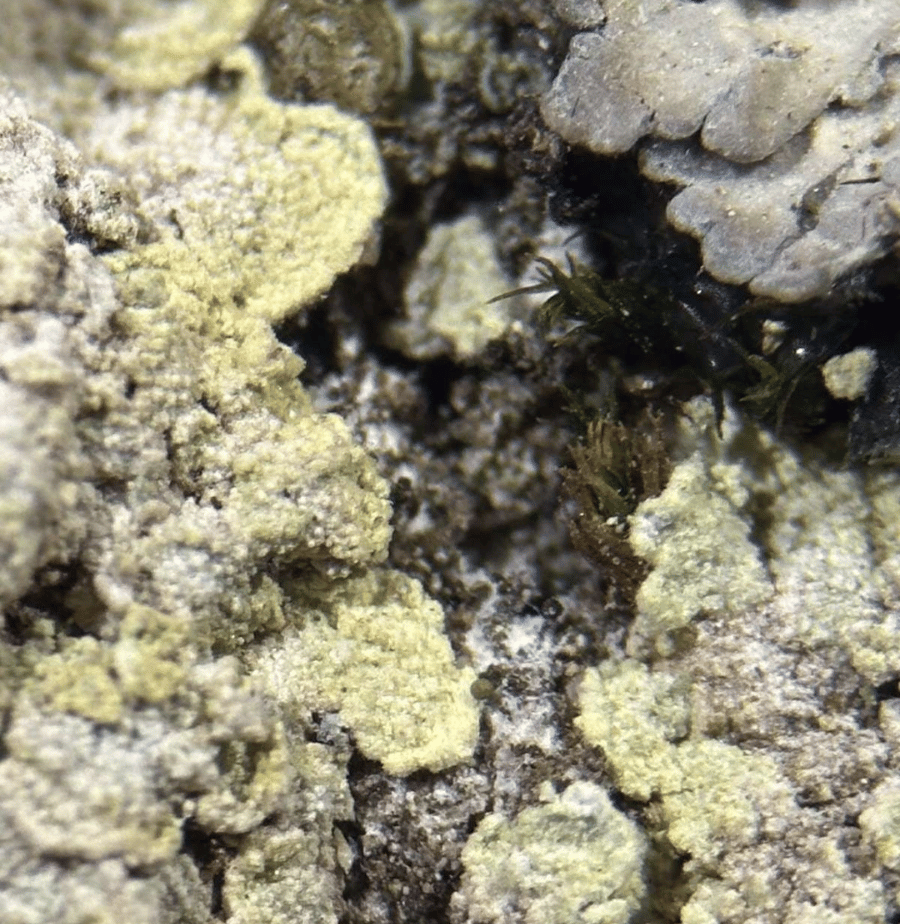

But then he was given a hand lens, a tiny, portable magnifying glass that can be used in the field, and looked at some lichen up close.

He said it was “a magical experience” and he “instantly fell in love.”

On that day, he changed his course of study. He was to be a lichenologist.

“Lichens are actually a composite organism of a fungus and an alga that have come together to make a living,” Watts explained. “The fungus will give the alga a place to live in exchange for some of the sugars from photosynthesis that the alga produces. So it's like a little house and then the algae forms a colony or lives inside the house.”

In other words: It’s a superorganism.

They named three new lichens … but there are only two members of the Indigo Girls. What’s up with that?

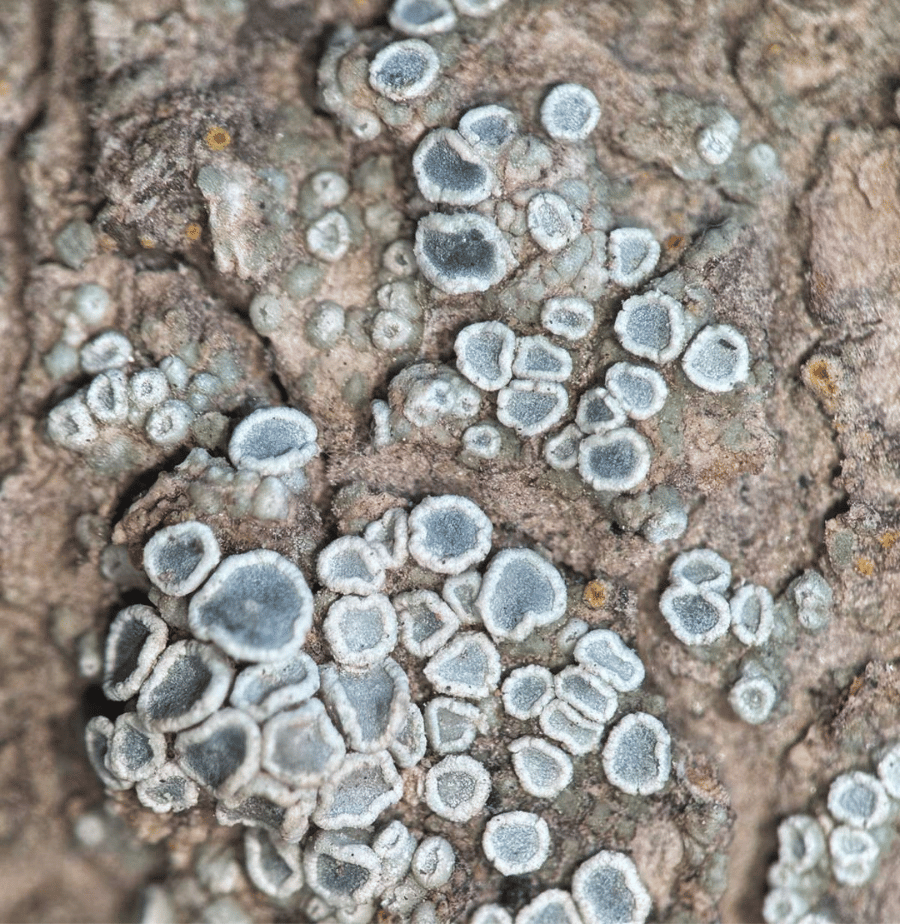

One lichen, Pertusaria rayana, is named for Amy Ray.

Another lichen, Lepraria saliersiae, is named for Emily Saliers.

And the third lichen, Lecanora indigoana, is named for the band itself.

“What made us want to name these three new species after the Indigo Girls was simply to honor their careers,” Manzitto-Tripp said. “Aside from their day job of writing and performing music, they have been lifelong activists, lifelong advocates for environmental health, ecological wellbeing, human rights, and honestly, the connectedness that happens between those two things.”

The trio reached out to the band’s management to let them know, but haven’t heard anything back.

“Which is fine,” Manzitto-Tripp said. “Our intention was hopefully just to get this message to those ladies to say, ‘Thanks. We wanted to honor you.’”

“It's frequently said, ‘You don't want to meet your hero anyway,’” Manzitto-Tripp added. “So just to know that they maybe received word that they'd been honored in this way would be wonderful news.”

A lichen by any other name would smell as sweet

Lichenology is a labor of love.

“We just want to know the names of things because names are the fundamental way we communicate about science, about knowledge,” Manzitto-Tripp said. “How can we conserve and protect things if they don't have names?”

So, she said, it becomes her job to name them. Then, she has to learn, “What are they doing? What are the ecologies? Where do they grow? What are their distributions? Who's rare? Who's common?”

All of this research is intended to build a foundation for the future study of lichen.

“You go anywhere in the United States, and we take for granted that there are not one, two, but 20 different field guides,” Manzitto-Tripp said.

For example, you can go to Rocky Mountain National Park and see a wildflower and wonder, “What is that?” Then, you can crack open a field guide, likely available in the Park’s gift shop, and identify it.

“You can't do that with lichens almost anywhere in the world,” Manzitto-Tripp said. “So our overarching objective here is simply to document the lichens of Colorado, comprehensively, for the first time ever in history.”

Then, she and her team hope to turn that research into scholarly articles and a popular field guide.

“It's a really infectious feeling.”

Collecting lichen is hard work.

“It's a lot to carry around,” Manzitto-Tripp said.

“If you feel the weight of this macro lens, that plus rocks, hammers, chisels, all your collecting gear. It's a lot to haul up and down mountains.”

“I think last summer I slept more nights in a tent than I did a bed,” Manzitto-Tripp said, adding that this summer has been similar.

In the field, the team has navigated unexpected road closures, inhospitable weather, and even a close encounter with a mountain lion.

But their love of lichen is unstoppable.

“It's a whole new world under the microscope,” Watts said. “It's just this magnificent feeling of, like, ‘Nobody's ever seen this before.’”