Testing wastewater was a key tool for detecting COVID-19 as that virus rampaged through the U.S. and Colorado when the pandemic hit.

Now, water treatment utilities and public health officials are joining forces to track, and for the first time in Colorado, identify in wastewater another highly contagious serious airborne disease caused by a virus: measles.

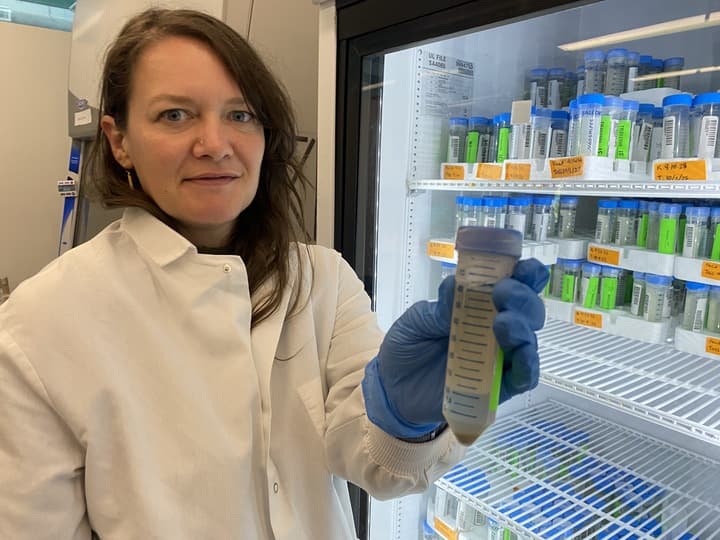

“Wastewater can be an early alert system and it can give us a community level view of what's going on,” said Shannon Matzinger, Genomics Surveillance Program Manager at the state lab in Denver.

Earlier this month, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment added measles wastewater surveillance data to its publicly available Wastewater Surveillance Data Dashboard.

The move came after a pilot program that started in May showed its effectiveness.

And it got an early test just months later when a measles outbreak hit Mesa County. Before infected and sick patients got positive tests in doctors’ offices, measles was already showing up in the wastewater data.

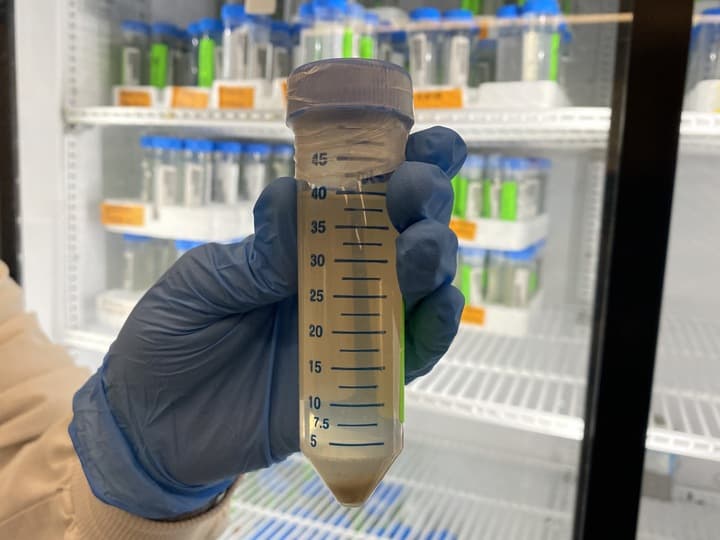

First it came in as just a low level detection of measles genetic material in a wastewater sample. Then came a very high level of measles virus detected in a sample from Grand Junction.

“So this to us was an indication that something was going on in Grand Junction,” said Allison Wheeler, the state’s wastewater surveillance manager, who said the state health department reached out to Mesa County Public Health and let them know. And sure enough, two days later they identified their first clinical case.

Information is a head start

The information was valuable, because it gave the community a head start as the number of cases began to climb, ultimately into the double digits.

“Once we confirmed the initial case of measles, we notified medical providers in the community,” said Erin Minnerath, Mesa County Public Health Deputy Director.

The samples that gave them the heads up were drawn from the Persigo Wastewater Treatment facility in Grand Junction. From there, they were shipped to the state lab in Denver, which used sophisticated viral detection and genomic sequencing, with help from sleek high tech machines which look like they could have been designed by Steve Jobs, to detect measles in wastewater.

“It was totally amazing,” said Randi Kim, utilities director for the City of Grand Junction, who said she’s been working in the field for decades. “It's all new technology that just has really evolved in the last few years. So, it's certainly nothing I conceived in my early career.”

Ultimate goal is prevention

The addition of measles data brings one more virus to the state’s wastewater surveillance dashboard. It already provides information on others: SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), influenza A and B, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), enterovirus D68 (EV-D68), and Mpox.

The technique is now also being used to look for drugs, like fenatyl.

Wastewater detection can ultimately help limit the spread of the viruses, giving doctors, nurses and patients valuable information and time. That can ultimately prevent illness, hospitalizations and even deaths, public health officials said.

“I think the most important thing that we can do with this information is message our local public health departments,” said Wheeler. They in turn hopefully can message their healthcare providers to say, ‘Hey, there's been a detection of measles.’”

Watching the wastewater

If you want to limit diseases spreading in your community, checking out what’s lurking in admittedly foul sewage water is proving more and more valuable.

Is there gold in that wastewater?

“It's not the gold that I would like, but you know, it is probably gold that public health likes,” said lab technician Kevin Castro, as CPR recently toured the state lab. “Yes, it is very fascinating.”

The reader’s digest version of how it all works goes like this, as the agency explains on its website.

By collecting and analyzing sewage you can understand disease trends in communities. And a big benefit is that you can do it without testing individuals.

“It’s non-invasive,” Wheeler said, meaning no one has to give a blood or urine sample or a cheek or nose swab.

It all works because people shed, or discard, viral, bacterial, and fungal particles into the water they use via things they do every day, like using the toilet, showering, or washing their hands. Sometimes this happens even when people aren’t showing any symptoms of illness.

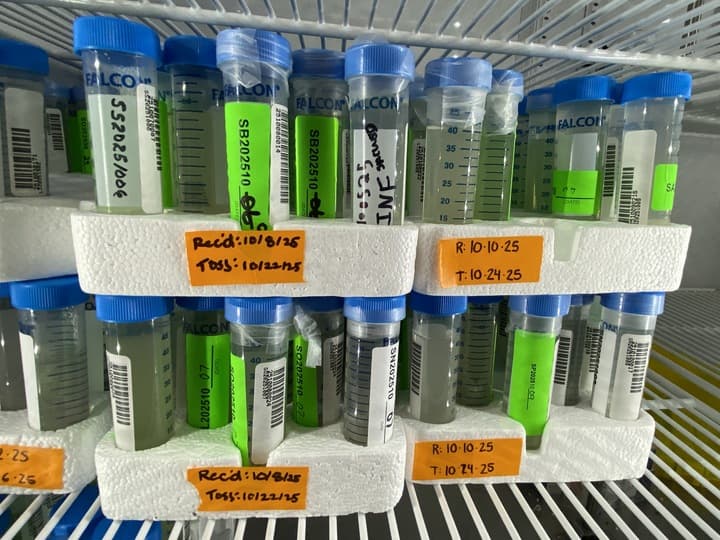

Wastewater utilities, like the plant in Grand Junction and 20 others statewide, collect samples twice weekly. They send them in vials that might equate to a small glass of water to labs like the state lab.

There, lab techs, like Castro, use sensitive methods like a PCR, or polymerase chain reaction test, like the one you probably heard about during the pandemic, to see which pathogens, also called germs, are circulating.

Gross? Cool?

What’s it like to deal with all this matter? Is it fun, is it gross, is it cool?

“Luckily for us, we get it already, you know, processed, so we don't have to do all the dirty stuff with it,” Castro said. “But I think it is very fascinating just having to see all the traces of all the diseases and all the viruses that are going on here in Colorado and just seeing how that progresses throughout the population.”

The data that gets collected and scientifically studied by those high tech-machines we mentioned earlier represents roughly half of the state’s entire population. That gives a window into broader illness or potential illness spreading in our schools, our business, our homes.

And it gives public health employees, really disease detectives, a way to detect illness trends without relying on people seeking medical care and testing.

It’s cost-effective, particularly when testing patients isn’t possible or hard to do.

The data is then used to see how diseases are spreading and it gets analyzed and posted to the state's dashboard, for doctors, nurses and really anyone to see.

And it gives public health officials and health systems an idea of things like where to conduct testing and vaccination campaigns, and make key evidence-based decisions for the wider health of the community.

A health forecast

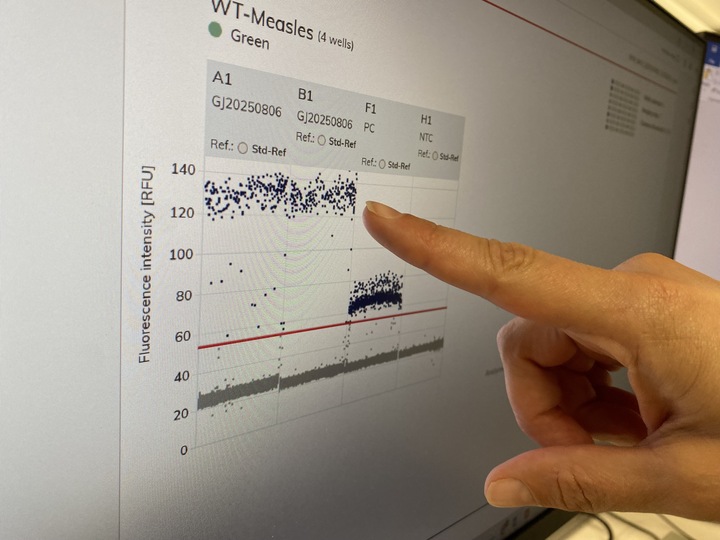

At a computer screen in her office, Matzinger, the state lab’s genomics surveillance program manager, showed how measles popped on a readout when the first positive samples came in from Mesa County.

“This is the first time we've seen a real detection (of measles) in wastewater,” she said, giving the state health department a chance to tell the public what symptoms to be on the look out for. In this case, she thinks it did limit the spread of the virus, which could have infected many more people.

Heading into the respiratory virtual season, that information can alert the public of, say, getting vaccinated sooner rather than later, or avoid certain situations, like crowded indoor spaces.

“It can be kind of that weather report for the public,” said Matzinger.