Two authors with ties to Colorado will receive $40,000 for their nonfiction books — even though they are not done with them yet.

The Whiting Foundation announced today that 10 authors — now hard at work on nonfiction books-in-progress already sold to publishers – will receive the grants in two $20,000 installments.

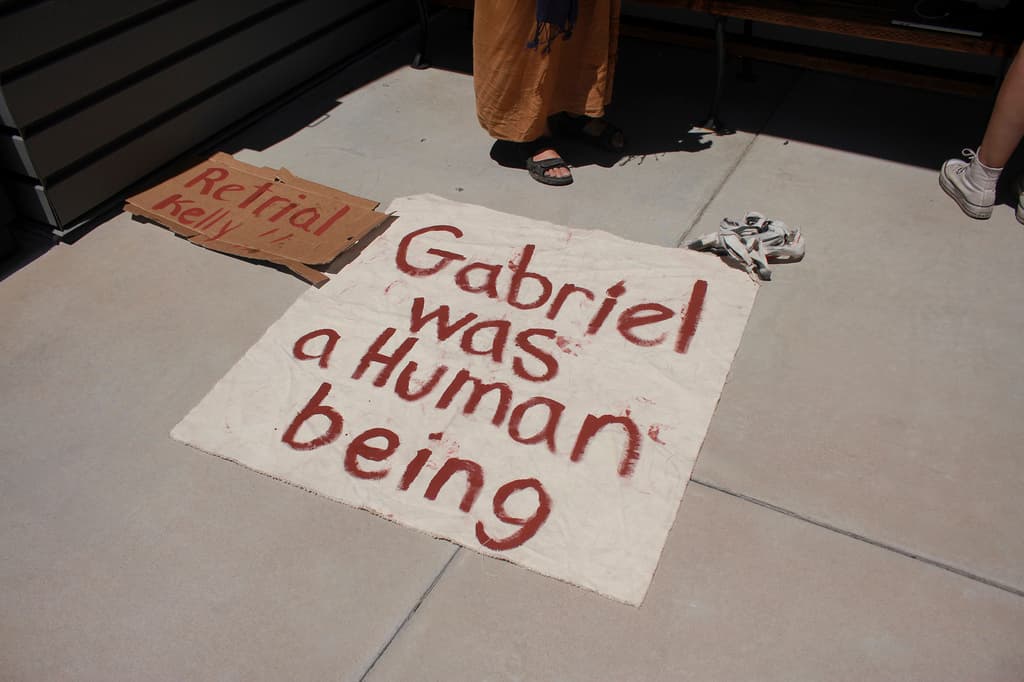

S.C. Cornell, 27, is one winner. Born and raised in Boulder, she is working on a book tentatively titled “The Migrant and the Murderer,” a true crime narrative focusing on a migrant from Mexico who was killed by a 74-year-old rancher while walking through the rancher’s Arizona property in January 2023. It is a topic she covered as a freelance journalist and decided to turn into a book.

With the first half of the grant, which she’s already received, she’s been able to expand the amount of reporting she’s been able to do.

“First, it just meant first being able to report with much more ease, being able to rent a car for a few weeks or stay in a hotel without worrying as much about how much money I was spending on reporting,” Cornell said. “And second, it just freed me up from having to do as much non-writing work to pay the everyday bills.“

The other winner with ties to Colorado is Raksha Vasudevan, an Indian Canadian, mostly self-taught freelance journalist. The 38-year-old now lives in the Sloan’s Lake section of Denver. She is working on a reported memoir, “Empires Between Us: Estrangement and Kinship Across Three Continents,” based on her five years living and working in humanitarian aid in Uganda and other countries in East and West Africa. The memoir is told from her point of view, being born to an upper-middle-class family in South India and then raised in Calgary.

“Thanks to the grant, I can really focus on the book until, I think, at least the summer, before I go back to full-time freelancing,” Vasudevan said. “I am nearing the end of a first full draft, which I thought would take me a lot longer. But I think because I've been thinking about this book and writing parts of it here and there for years now, it's actually come out pretty fast.”

The prize

The Whiting Foundation provides support for “writers, editors, educators, and the librarians and archivists who preserve our shared cultural heritage,” according to its website.

The Whiting Creative Nonfiction Grant of $40,000 “is awarded to writers in the process of completing a book of deeply researched and imaginatively composed nonfiction,” according to the website.

The foundation began giving out grants in nonfiction and other disciplines 40 years ago, in 1985.

“The Whiting Foundation recognizes that these works are essential to our culture, but come into being at great cost to writers in time and resources. The grant is intended to encourage original and ambitious projects by giving recipients the additional means to do exacting research and devote time to composition,” the website states.

S.C. Cornell

S.C. Cornell was born in outdoorsy Boulder, and attended language immersion programs at University Hill Elementary and Casey Middle schools in Boulder. That gave her strong enough Spanish that would come in handy later.

From Boulder, she went to Columbia University and earned a Bachelor’s degree in mathematics/economics, and then got a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing from New York University.

She wanted to break into journalism, but it was hard to make ends meet doing freelance writing for New York-based magazines. She had to add in some nanny jobs and restaurant work. A few years ago, she came up with the idea to move from the Big Apple to Mexico City, which allowed her to do the same work without spending so much time supplementing her income with side jobs.

She found an apartment and got to work, doing anything from writing book reviews for New York magazines to covering the trial of the rancher in the spring of 2024 — the subject of her awarded book. At court one day, she met the southwest correspondent for “The New Yorker,” who was also covering the case for that magazine.

“I mentioned to her that I was so interested in this trial, I was thinking I might write a book about it. And she put me in touch with her agent,” Cornell said.

She said the agent was initially skeptical, wondering if one trial was enough for a book. She won him over with the first 100 draft pages and an outline, and he agreed to represent her and reached out to editors.

One of them was the former editor of one of the magazines she freelanced for, who’d gotten a new job at Penguin Press. When the manuscript crossed her desk, she already knew Cornell — and now is serving as the editor of her manuscript. “That worked out phenomenally,” she said in an interview.

Cornell gambled that the book idea would become an actual book based on both her self-confidence and on her becoming an authority on the case.

“I think I have a lively voice,” she said. “I have a basic faith in my own abilities, mostly though I was thinking a lot about this idea of who is qualified to say what about what topics.”

She spent about a year following the case and some of its implications around issues of border sovereignty. When the case went to trial in 2024, she was a constant presence in the courtroom.

“I went to every day of the five-week trial, I interviewed or had access to interviews with all the main characters, and I just started to think, ‘You know, I’m probably the person in the world who knows the most about this particular day and what happened on January 30, 2023 in this square mile of the world’ … and that’s very empowering.”

She said she hopes to have the book finished next month, and that she anticipates Penguin Press publishing it about a year later, either at the end of 2026 or the beginning of 2027.

The Whiting judging panel said her work “becomes a real-life narrative with the emotional weight and immediacy of a novel. Cornell manages to humanize the migrants risking all to cross the border, the ranchers who see themselves as defenders of the land, and the jurors trying to make sense of it all.”

Raksha Vasudevan

Trying to make sense of it all is how Denver-based freelance journalist Rasksha Vasudevan came to start writing her own book, “Empires Between Us,” which she said blends her personal story with some independent reporting she did on what happens when things like aid workers, colonialism, skin color, nativism and privilege collide in east and west African countries where South East Asians also live.

“There was a lot of tension in those interactions and a lot of hostility,” Vasudevan said in an interview. “And I kind of found myself in between these different sides because sometimes I was recognized as South Asian, and then sometimes I was mistaken for white, which was also very puzzling and also made me just want to just realize that there's a lot going on here that I didn't understand.”

Her curiosity began in childhood. Now 38, Vesudevan was born in the state of Chennai in southern India and raised there until the age of 10, when her family moved to Canada. A formative moment in her childhood was when she saw — outside the gate of her home in an upper-middle-class community — a girl who could have been her twin, begging for money. She started wondering how their lives were so different when they looked so much alike. That enduring question led her to pursue work in her 20s at nonprofits and start-up organizations in West and East African countries, doing humanitarian and development projects she felt were her duty based on her privilege.

She began to grow disillusioned when she started to question whether the ideals of aid work ever came to fruition. After five years, she stopped in 2018, because she noticed she was often angry, feeling that her work was falling flat.

“I saw in aid, the projects that I was involved in, most of them weren't working. Most of them weren't changing anything,” Vasudevan said. “Most of them just seemed like a waste of money to me. And it just felt like, ‘OK, what am I doing here?’”

Looking to exit the aid world, she found a job at a small Denver-based firm that consulted on humanitarian topics. With no connections to Denver, she took the position.

“I got to encounter and often interview members of different communities. And so I had a lot of experience, felt pretty comfortable doing interviews and focus groups and calling people until they finally agreed to talk to me, which is a big part of journalism,” she said.

She worked at the Denver consulting firm for about two years, until around the time the pandemic began. By that point, she had enough money saved and enough practice under her belt to make a go of freelance journalism, writing for local and national print outlets.

At the same time, her thoughts lingered on her aid worker days on the African continent, including expectations “that the person or the community they're trying to help will be forever grateful to them, and they'll form this magical friendship that will transform all their lives,” which she said is a myth.

“Usually, even in cases of successful solidarity, people make mistakes. There are misunderstandings. Friendship isn't always the outcome. And so I think I was sort of confronting the limits of my fantasy towards the end of my time in Uganda,” she said of the manuscript, which, she admits, doesn’t have all the answers. “It's not a very prescriptive book. I do try to offer some examples outside of the formal aid industry of solidarity in action.”

She started working on the book, which has taken a few different directions, and now she is about 100 pages into her first draft.

The first agent she connected with didn’t work out, so when she found another to approach, she was hesitant: “I don't know what the chances are of its selling, but I just felt really strongly that I needed to write this book and that there was an audience for it.”

The agent worked with her on proposal revisions for a few months. Then it only took about a month to sell the manuscript to a large independent publisher, Graywolf Press. No publication date has been set, but she plans to complete a submittable draft by June 2026. Then she plans to spend the summer getting feedback and making improvements, before submitting it to her editor in August.

She also has a publisher in Canada, and has earned a combined advance of almost $25,000, which, with the Whiting Grant money, will allow her some time to breathe and focus on the manuscript, which the judges who selected it for the prize described as an analysis that “provides a considered perspective on the moral ambiguities in cross-cultural aid, shaped by histories of colonialism in India, Africa and Canada.”