Take a road trip through rural towns in Southwestern Colorado and you’ll probably miss two very small schools, each with about 80 students, where learning two versions of the Ute language is part of the curriculum.

Kwiyagat Community Academy is in a mobile building on the Ute Mountain Ute reservation, situated near other tribal buildings, including a community center and mobile offices. Inside, walls are decorated with animals significant to the Ute tribe, and school board President Tina King-Washington points out classrooms for spelling and other subjects, one of which doubles as a cafeteria.

It’s in there that about two dozen students are practicing introducing themselves, saying their names, then a word that sounds like “mike,” as a way to add in a hello. They’re members of the Ute Mountain Ute tribe, learning their native tongue — usually called a dialect because of its lack of written form.

They and other students are seeing expanded access to Native dialects and languages in their schools. In Denver, for example, some high schoolers are studying the Lakota language.

At Kwiyagat Community Academy, or KCA, several students are related to the teacher and teacher’s aide, either by blood or through tight community association, so the class feels as much like a family reunion as a lesson.

After going through how to introduce themselves and their parents, they rush out into the hallway to demonstrate “head, shoulder, knees and toes” in Ute. Their playful sing-songy voices and moves to touch different parts of their bodies make clear which children’s song they are singing.

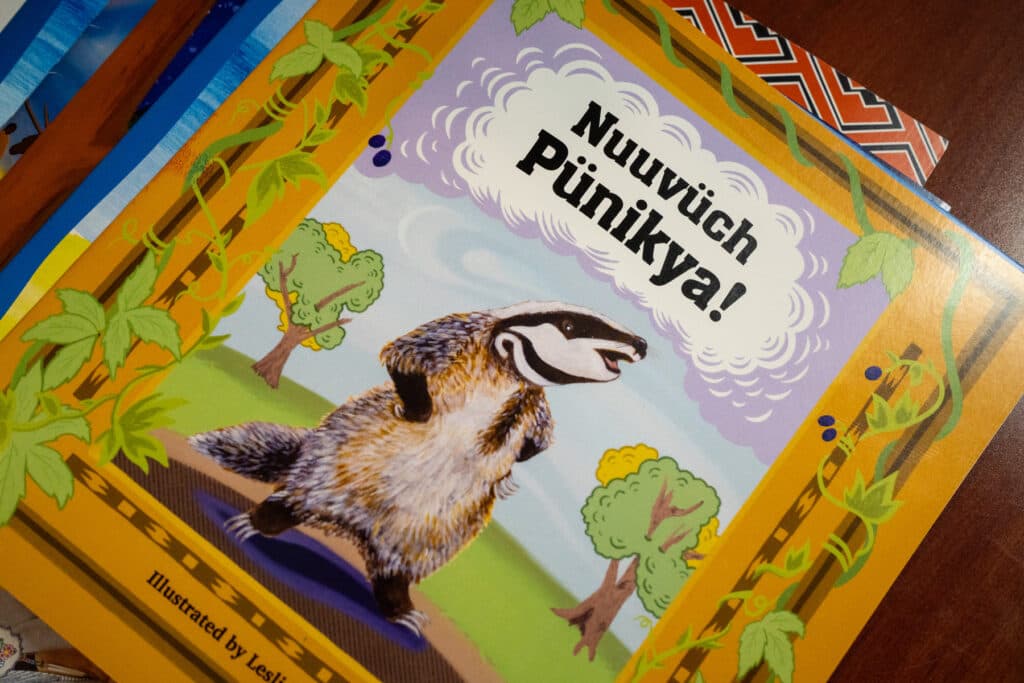

But there isn’t much rigor — beyond basics like colors, names, animals and such, developing a more complex understanding of grammar can be a challenge, because there aren’t that many people still living to learn it from. And even if there were, there’s not too much Ute available in writing to standardize the spelling of words.

That’s no surprise to Juanita PlentyHoles, 63, an Ute Mountain Ute tribal elder who has fairly solid Ute speaking skills. But even she knows there are some limitations. She said her mother, who raised her, didn’t speak English, so their common language was Ute. “I grew up with the language, so I understand it and I can talk to you, not perfectly, but I can talk,” she said.

To help add some structure and to capture some pronunciation that could die off when she and other elders are no longer here, she has been working with other elders — about 18 in all — who have language skills.

They have been working on a recorded dictionary through a grant. It’s part of an effort to enshrine a language fewer than a thousand people are likely to currently know.

She said that with the nonprofit Language Conservancy, they recorded over 10,000 words between 2018 and 2023. She considers this work her responsibility.

“When we think about our language, they’ve been passed on verbally. It’s survived all those generations. In the last 100 years or so, we’re losing it so quickly. I feel it's my responsibility to pass what I know on. One hundred years from now, we’re not going to be here, but our future generations are, they’re going to wonder, ‘I wonder how they say this word.’”

She added that there hasn’t been much attention paid to spelling and writing. “Ute is a spoken language. We’re just now in the process of working with the writing …. The writing part of it is new. Even our fluent speakers can’t read the writing.”

At Southern Ute reservation, it’s a similar situation, where a desire to learn, teach and preserve the language comes up against the fact that there are few resources with which to teach it.

In less than an hour’s drive, one can sit in on Ute at the sister reservation, where lessons in Ute look very similar, although there are nuanced differences between how both tribes speak it.

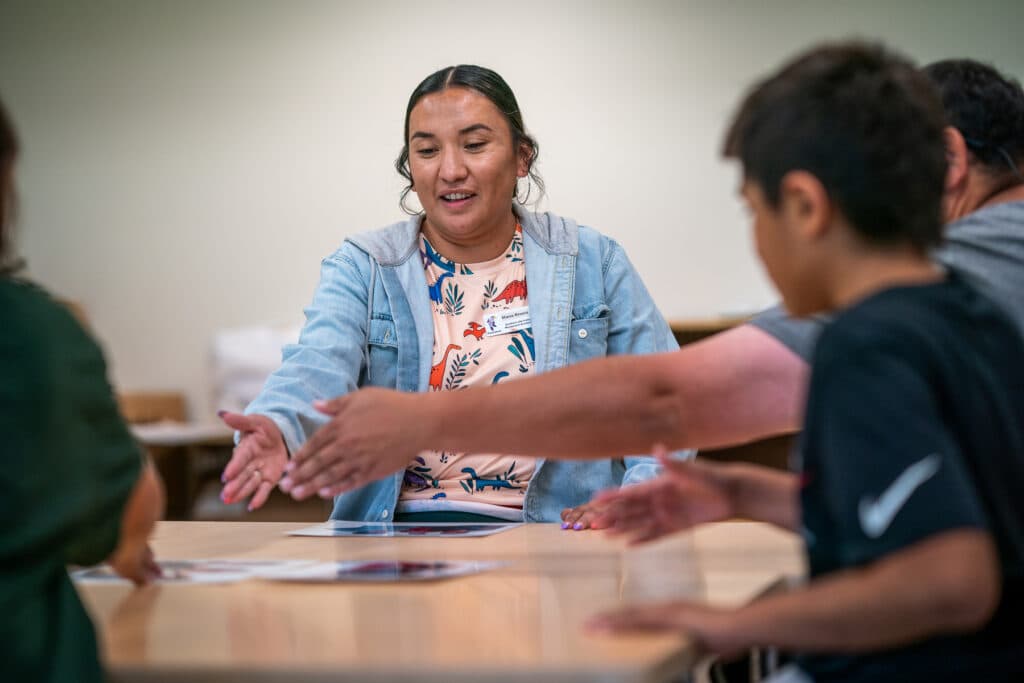

Southern Ute Indian Montessori Academy, commonly called SUIMA, is an elementary school with an enrollment of about 80, nearly identical to the enrollment at Kwiyagat Community Academy. At SUIMA, principal Mari Jo Owens, who is not Native, introduces herself with her given Ute name, then points out locations of classrooms and outdoor testing spaces where students can show teachers how much Ute they have learned.

Rhiannon Velasquez, a teacher there, helps students practice saying their Ute names. She refreshes their recollection of how to pronounce them, and children shoot back answers, comfortably saying some of the words they’d learned. Velasquez explains to students that naming is sacred in Ute culture. “It's an elder or a parent, somebody in our family,” who comes up with a name for a family member within Ute culture, she explained.

“Uusually, we don’t get a name until we’re older, it just depends on the family — sometimes it's based on the time of day they were born, what was happening at that time or something that reflects who they are.”

Her Ute name translates to “Cactus Flower.” Another student’s name translates to “One who holds the light;” yet another’s means “Fawn.”

Students seem engaged in the lesson, asking questions and participating, laughing and celebrating their correct answers with squeals and smiles.

There’s one main problem though, according to Principal Mari Jo Owens:

“Right now, at our school, we have no fluent speakers. So, some of us were fortunate enough to take a three-year course to be Ute language teachers. I’m one of them — I challenge myself to learn a new word or phrase everyday.”

Pointing out another faculty member, she said: “The teacher over there, she went through the three-year course, and then we have a Ute language teacher, she works part time . . .she was one of the instructors for us for that course.”

The point is: for a fully fledged authority on the language, there’s not someone to turn to who would have all the answers on definitive words and phrases.

Adding to the complexity is that Ute Mountain Ute tribal members speak a slightly different version of Ute than the Southern Ute tribal members, leaving those who want to gain the skills having to accept that perhaps they’ll be less than 100 percent.

The upside is that learning the language, no matter how incomplete, is a way to honor and remember the children who attended Native American boarding schools, one of which used to stand near SUIMA.

“If anybody heard them speak their language, they’d have wooden blocks placed in their mouths, or something worse,” Owens said of the time of the boarding schools. “Those students survived. So we get to keep the language going in honor of them.”