At Ute Mountain Tribal Park in Southwest Colorado, visitors show up promptly at 9 a.m., then join a tour with Ute guides who’ve led visitors through the home of ancestral pueblo Indians who lived there for over 400 years, between the years of 900 and 1340.

Once in a while, someone will leave, surreptitiously, with a shard of pottery they saw on the way – and then something might happen to them, or they’ll feel compelled to return it, guides there say.

At Mesa Verde National Park, 50 miles away, a much larger tourist attraction where ancestral Pueblo Indians lived during roughly the same time period, the same thing has happened: A visitor shows up, and comes across a shard of pottery, which ends up leaving the park with them. Later, they’ll feel guilty and give it back — an occurrence that’s the subject of a small display in the visitor’s center, complete with a note of apology.

Taking pottery shards away from where they were found is universally considered a no-no. Doing so disconnects the fragment from its context, which causes it to lose its value, archeologists and pottery experts and other scholars say. If, for example, a piece of pottery turned up somewhere away from its place of origin, it would be difficult for anyone but a pottery scholar to be able to know the right place to return it, thereby depleting the area of its history.

Although experts contacted for this story report not knowing of any studies on what happens when a shard, also known as a sherd, gets separated, or how commonly it happens, there is a 1979 federal law prohibiting it, and there’s plenty of local lore indicating it has happened in spite of the law, leading to, some say, consequences that could be physical, emotional, or legal.

Ute Mountain Tribal Park

To take a tour at Ute Mountain Tribal Park, all you have to do is call, make a reservation, then show up at the intersection of two rural roads in Towaoc. Tour guides take over from there. Rick Hayes has been leading tours there for 30 years — he’s often the one to give a day-long tour leading to ancient cliff dwellings that have withstood the test of time.

Guests can drive themselves while following a guide, or ride in their truck, seeing all around a monochromatic landscape of dusky beige sand and large brown rocks, boulders and cliffs. Throughout, guides point out horses that somehow survive there, probably getting food and water in a canyon inaccessible to humans. There are also petroglyphs still visible in red on rock walls, and pottery shards that date back centuries.

In a recent telephone interview, he said there has been chatter around the office, buzzing around a story of a former guest coming into the office with a few pieces of pottery to return. The donor said they were found in the closet of a beloved granddaughter, who had recently died. Cleaning out her room, they found them, not knowing they were there.

When asked if he’d heard first-hand a story of someone bringing a shard back, he belly-laughed and said, “If they did, they probably wouldn’t tell me about it.” With brown skin, two braids on his shoulders, and a distinctive accent, he didn’t look the part of a person to whom a visitor would make such a confession.

Dressed for a tour one day in a flannel and jeans, he spoke reverently of the pottery shards and their importance at the tribal park, a scrappy little tourist attraction without the notoriety of the larger Mesa Verde National Park 50 miles away. “It’s disrespectful to the ancestors. Those shards are a reminder that our ancestors prayed for us.”

At destinations throughout the tour, guides pull over; everyone gets out, and guides call to the attention of visitors shards of pottery likely used for cooking, storing and serving food. Some are covered with pieces of wood to protect them from view until the guide decides to reveal them. Many are white and black with intricate carved designs, ranging in size from less than an inch in size to an 8-inch, three-dimensional fragment that appeared to be a portion of a bowl, with the handle still attached, to one bowl almost fully intact.

The expectation is that people would not take them, according to another long-time guide, Beverly Lehi-Yazzie. “They are all connected,” she said, meaning the shards of pottery are connected to the land where they are found.

Walking up an embankment with a sun visor and walking stick, she looked over her shoulder and said to a half-dozen guests with her one morning: “You don’t want to take ‘em, or else bad stuff could happen.”

In an interview later, she recalled a day when she went to the administrative office from where tour-takers check in, pay their fee, and then decide if they want to take a tour in the vehicle of a guide, or follow in their own vehicle. Before she could step through the door, she bent down and found a shard sitting on top of a note.

“They said ‘Sorry,’” she said with a laugh. She said she also has heard the local lore at the tribal park that someone took a tour, pocketed a shard, then promptly fell ill. She didn’t know the details, but said it’s a story that has circulated around, like Hayes’ about the return of the shards from the closet of a granddaughter who’d died.

Such stories are to be taken seriously by all visitors, because the spirits of the ancestors will know, said Lehi-Yazzie, who is Ute and commutes from Utah to give tours during warmer months. “Sometimes, out there, you can feel like someone is watching,” she said, adding that she often feels the presence of ancestors while she treks through the rocks, up and down little hills and valleys, sharing with guests the history of her people.

Mesa Verde

While the tribal park is an unassuming place, without a PR team or large staff, and is owned by the tribe, Mesa Verde National Park — also an outdoor oasis where visitors learn of and see ancient cliff dwellings and other artifacts created by ancestral pueblo Indians who lived there in structures still standing centuries later — is a more oiled machine.

It has a staff of about 100, and gets half a million visitors a year who come to find out about ancestral pueblo Indians who lived in hand-made rock structures from the year 550 until 1300.

Having departed from the area, they left behind visual remnants of their time there, including 600 cliff dwellings. Over 700 years, they built more than 4,700 structures: pithouses, towers, kivas and cliff dwellings carved into sandstone. Starting in the 1270s, ancestral people migrated to lands that has become New Mexico, Arizona, and other states in the southwest. Now, members of about two dozen pueblo communities in those states claim descent from the original people from Mesa Verde.

At the much bigger operation accessible after a long drive off a main road near Durango, there’s an internship program, a museum, a visitor’s center that shows a 17-minute film, rangers walking around in hats and khaki uniforms, and a bunch of tour options guests can choose from. There’s a tame one guests can listen to while driving in their car — and a much more adventurous one involving a thirty-foot ladder climb, to see cliff dwellings otherwise inaccessible.

Regardless of the difference in size and additional bells and whistles, the pilfering of pottery shards, although not common, has happened at Mesa Verde too — enough so that the National Park has created a small display in the visitor’s center museum to highlight the act.

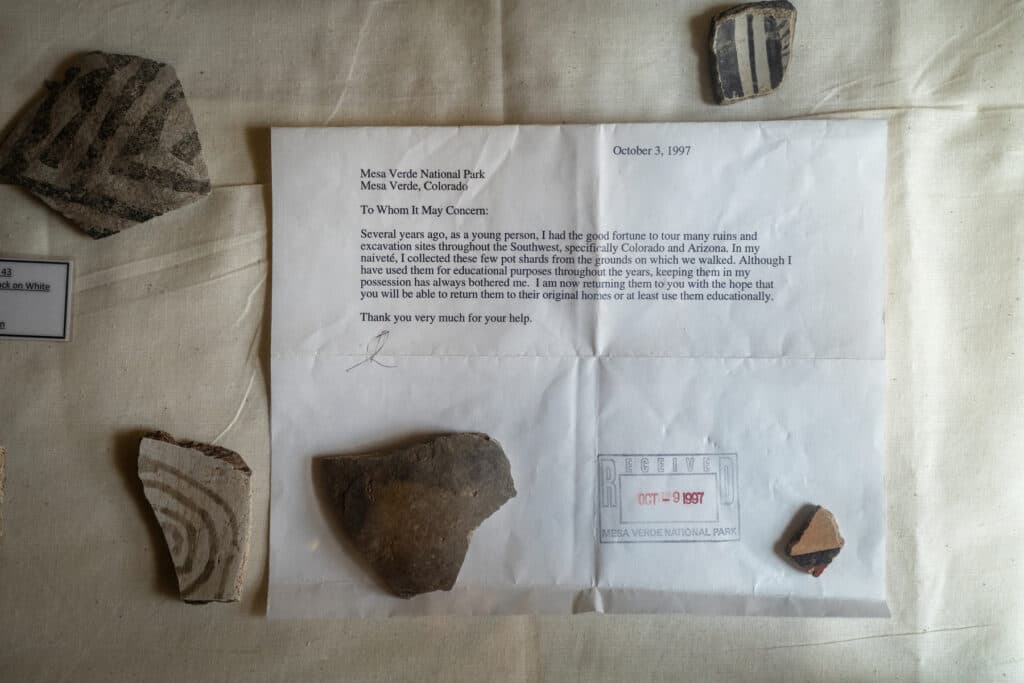

In an enclosed glass case several feet square, there are a few fragments, small triangular-shaped — all pottery shards that went on an off-park adventure, and then got brought or mailed back.

Alongside the shards is a note from Oct. 3, 1997, written by an anonymous returner:

To whom it may concern, several years ago as a young person, I had the good fortune to tour many ruins and excavation sites throughout the southwest, specifically Colorado and Arizona. In my naivete, I collected these few pot shards from the grounds on which we walked. Although I have used them for educational purposes throughout the years, keeping them in my possession has always bothered me. I am now returning them to you, with the hope you will be able to return them to their original homes, or at least use them educationally. Thank you very much for your help.

Ranger Dalton K. Dorrell, a spokesman for the park, said he wasn’t sure who created the exhibit. “It's something I look at every time I pass that table, that exhibit … I love that exhibit, too.”

The Law

Although some people’s conscience nudges them to return shards, others may need a nudge from the strong arm of the law. The Archeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 made it a crime to, among other things, remove shards of pottery from national parks where Native Americans once lived.

The purpose: “To secure, for the present and future benefit of the American people, the protection of archaeological resources and sites which are on public lands and Indian lands, and to foster increased cooperation and exchange of information between governmental authorities, the professional archaeological community, and private individuals having collections of archaeological resources and data which were obtained before October 31, 1979,” according to a posting by the National Park Service.

Not all Coloradans have paid attention. In 2020, Lonnie Shadrick Winbourn, a Cortez, Colorado man, was sentenced a year an a day in federal prison for stealing Ancestral Puebloan artifacts in 2017, according to media reports. The artifacts included pottery and jewelry from the Canyons of the Ancients National Monument near Mesa Verde,

According to the report, Winbourn “discovered a ceremonial site with a large dance plaza, subterranean kiva and multiple human burials;” from it he took 64 items. “When he was pulled over and arrested on an unrelated warrant on June 4, 2017, officers said they found pottery shards in his pocket and Puebloan artifacts in his backpack …. Winbourn also stole jewelry, an ax head and other tools, according to prosecutors.”

Dorrell said the glass-enclosed mini exhibit in the Mesa Verde visitor’s center museum is, like the law, also meant to be an instructive deterrent, and not only at that national park: “It's a tool that we've used, I would say [for] decades in national parks in this sort of setting, because it is so moving, and it shows that people learn; people grow. Like even the people that maybe took a pot shard and decades later they realize, ‘You know, I learned more and realized and thought about it and sent it back.’”

- These elementary schools in Southwest Colorado are trying to save the Ute language

- A Ute Mountain Ute spiritual leader reflects the importance and private nature of vision quests, sun dances, and sweat lodge ceremonies'

- Visitors to Southwest Colorado’s Mesa Verde National Park can now hear from its direct descendants