While the National Endowment for the Arts has prompted plenty of political debate in the past, Donald Trump is the first president to formally target the agency. The White House’s 2018 budget outline aims to eliminate the NEA, whose budget neared $148 million in 2016.

Cultural groups around the country, from art museum associations to Hollywood unions, have decried the proposal. Jumpstarted by Congress in 1966, the NEA has helped fund all sorts of efforts like the American Film Institute, "A Prairie Home Companion" and the Aspen Santa Fe Ballet.

That got us wondering about how the NEA impacts Colorado. How much money does the state get? And where does that money go?

In total, Colorado received $3,134,600 from the NEA in 2016. Those grants went directly to 38 different agencies, groups and schools. Here’s the thing: The Western States Arts Federation got more than half of that money. As a regional arts organization, WESTAF is headquartered in Denver, but works with 12 other states. Each receives some of this NEA funding.

Colorado’s NEA money has gone up since 1998 -- that’s as far back as the agency’s digital records go. See the significant spike in 2009? That’s due in large part to the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, President Barack Obama's stimulus package, which granted the NEA an additional $50 million to preserve nonprofits arts during the downturn. Since then, Colorado’s direct annual pull of NEA funds, minus WESTAF, has averaged just over $1.3 million.

WESTAF distributes NEA funds across several states. About half of that money supports a specific program called TourWest, which gives up to $2,500 to smaller nonprofit presenters and cultural venues. They use those grants to host professional artists and groups that tour the region.

Recently, Colorado’s share of TourWest grants has totaled nearly $50,000. Recipients include Su Teatro in Denver, Paonia’s Blue Sage Center for the Arts and the City of Lone Tree. WESTAF also uses NEA money to offer professional services for arts leaders and to host conferences, which periodically take place in Colorado.

Finally, a bit of the NEA money goes toward administrative and operational costs, according to the organization. Each state does pay a participation fee to WESTAF.

What would happen to the organization if the NEA goes away? Well, it wouldn’t spell the end for WESTAF because it generates most of its budget through the majority share of a technology systems developer.

“We are probably better positioned to survive because we have so much earned income,” says WESTAF executive director Anthony Radich. “(Eliminating the NEA) would still have an impact, it would slow us down, and there are some things we wouldn’t be able to do.”

It’s no surprise that Denver is the largest beneficiary of NEA money, followed by other Front Range cities. Recipients of 2016 grants included the Denver Art Museum ($70,000), Lighthouse Writer’s Workshop ($30,000), and the Colorado Dragon Boat Festival ($10,000), the Crested Butte Music Festival ($10,000) and the M12 studio and artist collective in Byers ($10,000).

Now let’s talk about that top line: Colorado Creative Industries. The state’s arts agency works closely with the NEA and not only allocates the funds it receives from the endowment, but it also matches them. A lot of this money provides general operating support for rural groups, from the Pueblo Symphony Association, to Ridgway’s Sherbino Theater, to the Crow Luther Cultural Events Center in Eads, to the Creede Repertory Theatre in — where else — the small mountain town of Creede.

“That NEA seal of approval has made it so much easier to attract and secure matching funds, other grants and to leverage resources,” says Creede Repertory Theatre’s executive director Catherine Augur. “It’s critical for us to have that, and we’re nervous that if that (NEA) funding goes away, it would just be harder to secure that outside funding.”

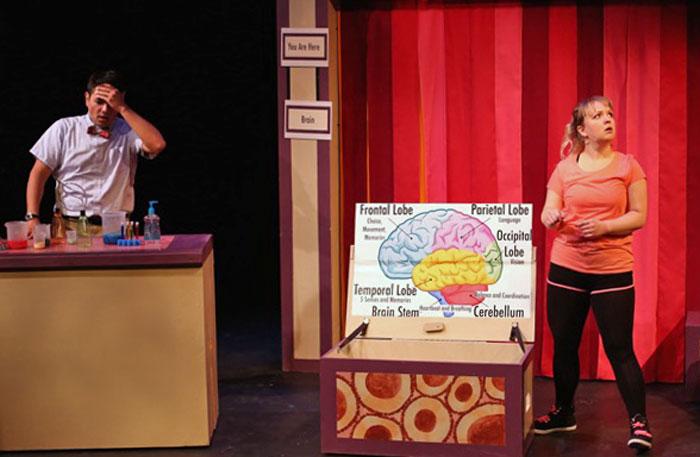

Creede Rep gets $10,000 to $20,000 in NEA grants annually for its young audience outreach tour, which takes an original, bilingual musical to rural schools across states like Colorado and Arizona.

“For many of the students, they would not see or have the opportunity to experience performing arts otherwise,” Augur says.

A Few Other Things To Keep In Mind

Colorado’s annual share of NEA funds (including the money for WESTAF) has hovered around 2.7 percent for the last decade. Many arts advocates and cultural leaders we’ve talked to have yet to hit the panic button, since this matter will play out over time.

“We’re very disappointed in the proposed budget, but we are prepared,” Colorado Creative Industries director Margaret Hunt says. “We understand that this is the first step in a lengthy process. It’s got a long way to go with a lot of input before it’s finally decided.”

Hunt points out that the NEA does plan to fulfill all of its grants for the 2017 fiscal year.

It’s also important to note the Denver area has a bit of a cushion thanks to the Scientific and Cultural Facilities District. The cultural fund, which stems from a sales tax covering seven counties, generated more than $56 million in 2016. Again, for comparison, that’s more than a third of the NEA’s overall budget.

So with NEA funding on the line, this leads to the question: Will we see more cities, states and regions pursue their own mechanisms to publicly fund arts and culture?

What questions about NEA funding do you have? Tweet us your questions @NewsCPR, email [email protected] or leave them in the comments below.