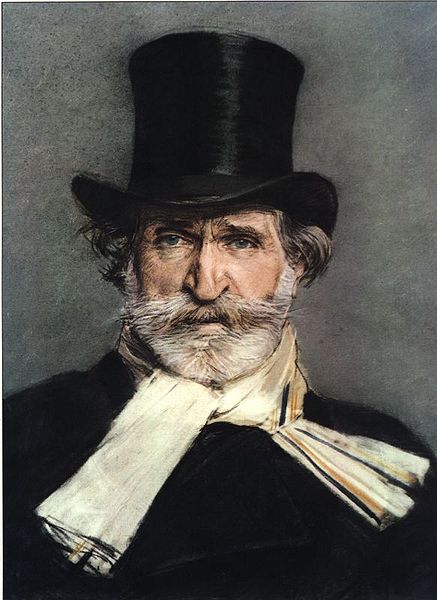

Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901): Requiem I. Introit (Requiem aeternam) & Kyrie II. Sequence (Dies irae) Tuba mirum Liber scriptus Quid sum miser Rex tremendae Recordare Ingemisco Confutatis Lacrymosa III. Offertory (Domine Jesu) IV. Sanctus V. Agnus Dei VI. Communion (Lux aeterna) VII. Responsory (Libera me, Domine)

The death of Rossini in Paris on November 13, 1868 prompted Verdi to propose a novel idea. Italy's leading composers would contribute one movement each to a composite Requiem Mass in Rossini's memory. Verdi finished his part of the scheme, the “Libera Me,” and the other parts were assigned to musicians named Buzzolla, Bazzini, Pedrotti, Cagnoni, Ricci, Nini, Coccia, Gaspari, Platania, Petrella, and Mabellini. Somehow, the scheduled performance never took place.

When a conductor suggested that Verdi finish the Requiem on his own, he replied: “I have no love for useless things--Requiem Masses exist in plenty, plenty, plenty! It is useless to add one more to their number.” But Verdi changed his mind on hearing of the death of his idol, the novelist Alessandro Manzoni, on May 22, 1873. “I have not heart enough to be present at his funeral,” he wrote to his publisher. “I shall come soon to see his grave, alone and without being seen, and perhaps...propose something to honor his memory.”

What Verdi had in mind was adding the other movements to a revision of his original “Libera Me” of five years before. He wrote to the Mayor of Milan: “It is a heart-felt impulse, or rather necessity, that prompts me to do honor as best I can to that Great One whom I so much admired as a writer and venerated as a man.” By April 16, 1874, he reported: “That devil of a Mass is finally finished.”

The first performance of Verdi's Requiem took place in St. Mark's Church in Milan on the first anniversary of Manzoni's death, May 22, 1874. One critic praised all the sections of the work, especially the “Dies Irae,” “a poem full of things terrifying and at the same time moving and pathetic.” Three days later, Verdi conducted the work at La Scala. According to one account, “the applause changed to roars which, though stifled, even broke out during the actual performance, so irresistible was the inspiration of the music.” Afterwards, Verdi was given a silver crown.

Not everyone shared the enthusiasm of La Scala's patrons. Cosima Wagner noted in her diary: “In the evening Verdi's Requiem; it is decidedly best to pass over that thing in silence.” Hans von Bülow dismissed the music as Verdi's “latest opera in ecclesiastical garb.” Johannes Brahms had a different view: “Bülow blundered; this is the work of genius.” Indeed, Bülow later apologised to Verdi. Verdi's wife Giuseppina wrote: “Posterity will place it, with wings outspread, in domination of all the music of mourning ever conceived by the human brain.”

Traditionally the Roman Catholic Requiem Mass is said on All Soul's Day (November 2), or at a funeral or anniversary of someone's death. A tradition of setting certain sections of the Mass arose in the Requiems of Mozart, Cherubini, Berlioz and others. After the “Requiem” and “Kyrie” comes the central section, “Dies Irae” (Day of Wrath), a medieval poem by St. Francis of Assisi's friend, Thomas of Celano. In Verdi's setting, writes George Martin, “Verdi knocks the world apart with the violence of his music. Four cracks of doom from the orchestra, and the voices begin the dizzy slide into blackness. No one can possibly not pay attention.” To the usual Requiem movements--”Offertory,” “Sanctus,” “Agnus Dei” and “Lux Aeterna”--Verdi added the “Libera Me.”

In his biography of Verdi, Francis Toye writes: “Verdi here produced a work that may leave something to be desired as a expression in music of ecclesiasticism or even of spirituality, but that, as an interpretation of the hopes and fears of mortal men, could scarcely be more poignant and certainly not more sincere.”