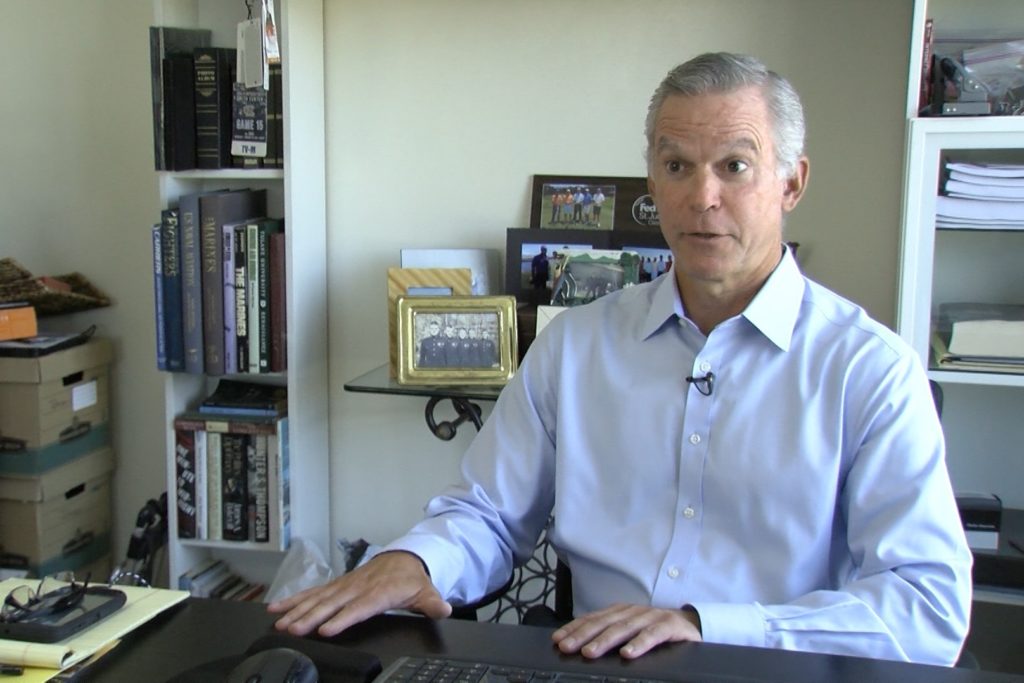

Mark Coast spent 20 years as a special agent with the Drug Enforcement Administration. Before he retired last year, Coast also spent 30 years in the Marines, most of that time in the reserves.

Coast served four tours in Iraq as a Marine reserve officer while on leave from the DEA. He's now part of a lawsuit with 15 other DEA agents from San Diego who allege the agency discriminated against agents serving in the military.

"Never in my wildest dreams did I or any of my colleagues assume that we would get the most grief from our office," Coast said. "That was the most incredible thing I experienced as a result of the wars."

In their lawsuit, Coast and the other agents say they were denied promotions after returning from military service. One agent was moved to an office hours away from his home. The agents contend that supervisors made it clear that they believed military service was taking too much time away from the agents' full-time jobs.

Coast says one of his supervisors came up to him in the mailroom after he came back from his first tour in Iraq.

"He was asking me about my experiences," Coast said. "I said yeah, it was pretty hard fighting up to Baghdad. I got wounded at one point. And he said, 'You know, if you hadn't stayed in the reserves, this wouldn't have happened, so you pretty much deserve everything you get.'"

The DEA won't comment on ongoing litigation.

Congress passed the Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act in 1994. The number of cases filed under the law remained relatively small in the 1990s. That changed after the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan required military leaders to use thousands of guard and reserve troops.

Though the number of reservists being called to active duty has dropped since the height of the conflicts, the level has never gone back to what it was prior to the Sept. 11 attacks, said Patrick Boulay, director of USERRA enforcement for the U.S. Office of Special Counsel.

"This law helps keep our military all-volunteer by giving people employment protection and protections against discrimination when they're trying to get a civilian job," Boulay said.

The law specifically says that the federal government should be a model employer, but statistics from the Department of Labor show that over the last decade, about 17 percent of all cases under the law have been filed against the federal government. The worst offenders are agencies most closely tied to the military. The civilian side of the Department of Defense saw the most cases filed against it - nearly 497 - followed by the Departments of Veterans Affairs and Homeland Security.

"One could argue that it's because they employ a lot of veterans and service members, but of course we also want these agencies to do their best not to violate the law," Boulay said.

One problem is that USERRA is designed to get relief for individuals, Boulay said. His office has been able to work out agreements with agencies to ensure the law is applied properly in particular cases, but he said he can't force an agency to change its policies toward reservists, so similar problems keep cropping up.

The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled in February 2018 on the amount of paid leave federal reservists are allowed. Brian Lawler, a retired Marine reserve aviator and a lawyer in San Diego, has filed essentially the same lawsuit over and over to force federal agencies to follow that ruling.

"Every other week, an agency will say, 'We don't agree with that decision,' which they can say, but I know how it's going to turn out in the end," he said.

The Department of Labor only tracks cases filed through its office, not cases filed by outside attorneys such as Lawler. Most of his clients are reservists, and half of his cases involve federal employers.

"We represent a gentleman who is a senior officer in the Army reserve and a senior civilian employee working for the exact same command, who is being denied benefits of his reserve service by the exact same command he works for as a civilian," Lawler said.

The legal process can take years. At the moment, the process is especially slow. The Merit Systems Protection Board, which oversees appeals by federal workers, hasn't met in more than a year. The Trump administration was slow to make appointments to the board, and the Senate hasn't confirmed any new members.

The board has a backlog of 2,300 cases waiting for review, according to a statement released by William Spencer, the board's acting executive director.

This story was produced by the American Homefront Project, a public media collaboration that reports on American military life and veterans. Funding comes from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Copyright 2019 North Carolina Public Radio – WUNC. To see more, visit North Carolina Public Radio – WUNC.9(MDEyMDcxNjYwMDEzNzc2MTQzNDNiY2I3ZA004))