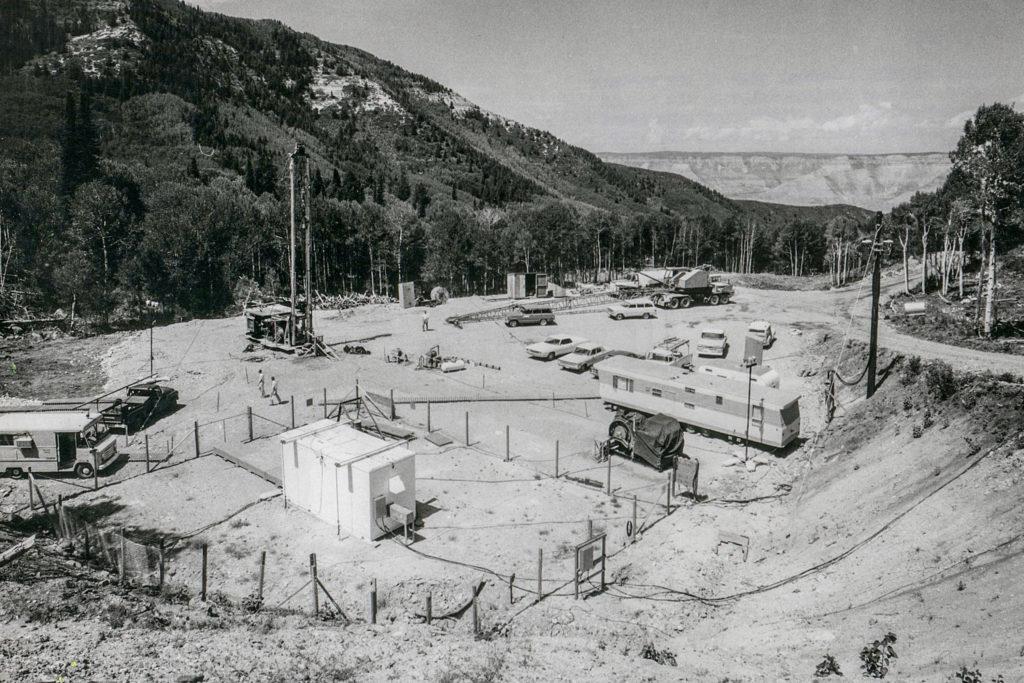

Fifty years ago, scientists detonated a nuclear bomb underground with Project Rulison, an effort designed to unlock natural gas trapped in stubborn shale. The goal sounds familiar: launch an economic boom fueled by oil and gas. The tool they used was not.

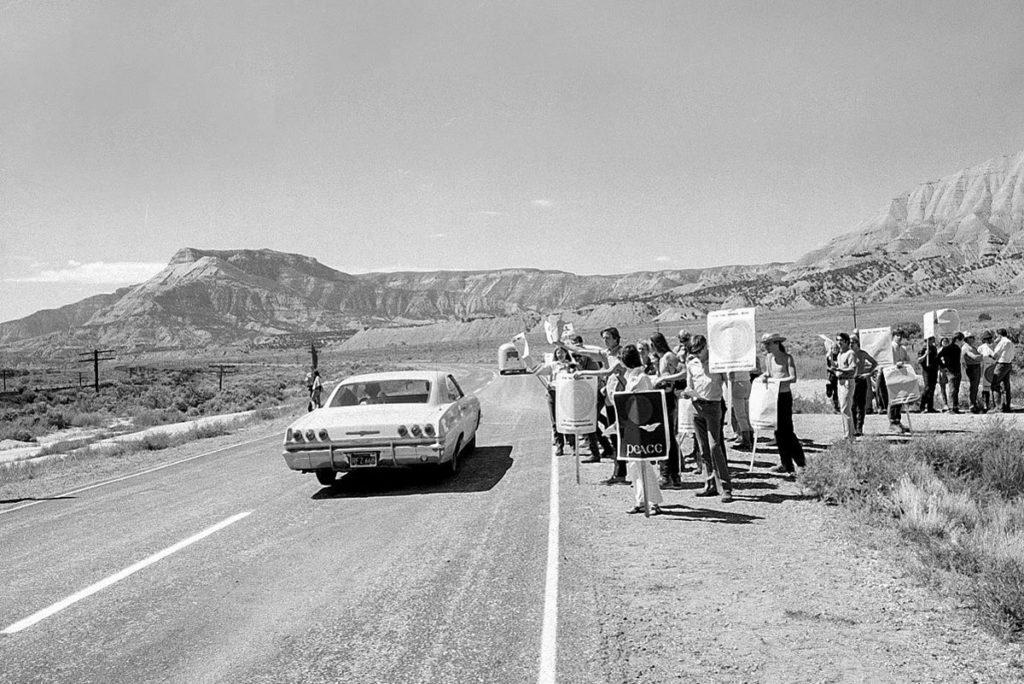

During the summer of 1969, activists from Denver and Boulder organized to stop the Sept. 10 detonation. They had concerns about radioactive contamination. They also worried about what the future would hold if federal scientists had their way.

They couldn’t convince the courts to act, so they first turned to direct action.

“It pushed the buttons of a lot of people,” remembers Chester McQueary, who hiked into the Project Rulison blast exclusion zone all those years ago in an attempt to stop the experiment.

A larger group of 12 environmentalists split into smaller groups of three or four. As the detonation time approached (a minute-by-minute update was broadcast on a local radio station), McQueary’s group set off a smoke flare to let Atomic Energy Commission scientists know they were 2 miles from the blast zone.

Helicopters suddenly appeared to try to clear them out.

“They were yelling at us,” he remembered. “But with the intense noise, we couldn't understand a word they were saying.”

McQueary ran away with his group to find a clearing and rode out the blast — they didn’t stop it. The noise sounded like the loudest freight train he had ever heard rumbling underneath.

“We were lifted six to eight inches in the air when the shockwave hit us,” McQueary said. “This was to be a test, but they said openly at the time that if it was successful then they planned in the 20 mile stretch between the towns of Rifle and Parachute they would set off between 100 or 200 of these nuclear blasts to fully develop the gas field.”

The industrial sponsors of the project, Texas-based Austral Oil Co., had high expectations in the early post-detonation results. So much so, that a company assistant vice president, Miles Reynolds Jr., told The Denver Post in 1970 that serious consideration was due for additional developments using smaller nuclear devices.

“Everything so far exceeds our expectations — gas volumes, rates of flows, corresponding pressures, even the low levels of radioactivity,” Reynolds said in a Post report, 13 months after the blast.

The Rulison nuclear detonation did not release radioactive elements into the atmosphere. However, subsequent venting tests of the natural gas in 1970 and 1971 did release small amounts of radioactivity. Rulison was just successful enough that federal scientists followed up as part of their larger Plowshare Program to do more. In 1973, they detonated three bigger nuclear bombs underground in Rio Blanco County.

Both tests pushed environmentalists like McQueary into a new tactic: Limit nuclear tests with a statewide ballot initiative. Measure 10, the Colorado Detonation of Nuclear Devices Amendment, prohibits the detonation of nuclear explosives in Colorado unless voters approve it.

“[Scientists] had their devices, and they had their grand scheme of creating 300 trillion-plus of natural gas supply,” McQueary said.” They were not going to be deterred by some stupid protesters trying to disrupt their plan.”

But a state constitutional amendment did slow down the scientists. The 58 percent share of the popular vote was largely fueled by voters in the Denver metro. Even voters in Rio Blanco and Garfield counties approved the measure. One of the few outliers of the time was nearby Mesa County, which went against the amendment.

The federal government shut the Plowshare Program down in 1975. In the end, not a cubic foot of natural gas was ever sold from the Rulison well due to radiation and the Rio Blanco test was considered a failure.

Every now and again, the idea of using atomic weapons to solve a problem in the natural world rears its head. Some scientists wondered if a nuke could stop the BP well gushing into the Gulf of Mexico. Axios reported that President Donald Trump wondered whether a nuclear bomb could stop Hurricane Dorian. The president has denied the story.

“Something that concerns me is the possibility that Plowshares could come back,” said Scott Kaufman, author of a history book on Projects Rulison, Rio Blanco and other Plowshare efforts.

Kaufman notes that fourth-generation nuclear power promises to be cleaner compared to previous efforts. But he warns the country would be wise to learn from this chapter in history.

“What kind of shaking will [the explosions] cause? Can we guarantee that the blast will be clean, or will it release some radioactivity? We just don’t know answers to that,” Kaufman said.