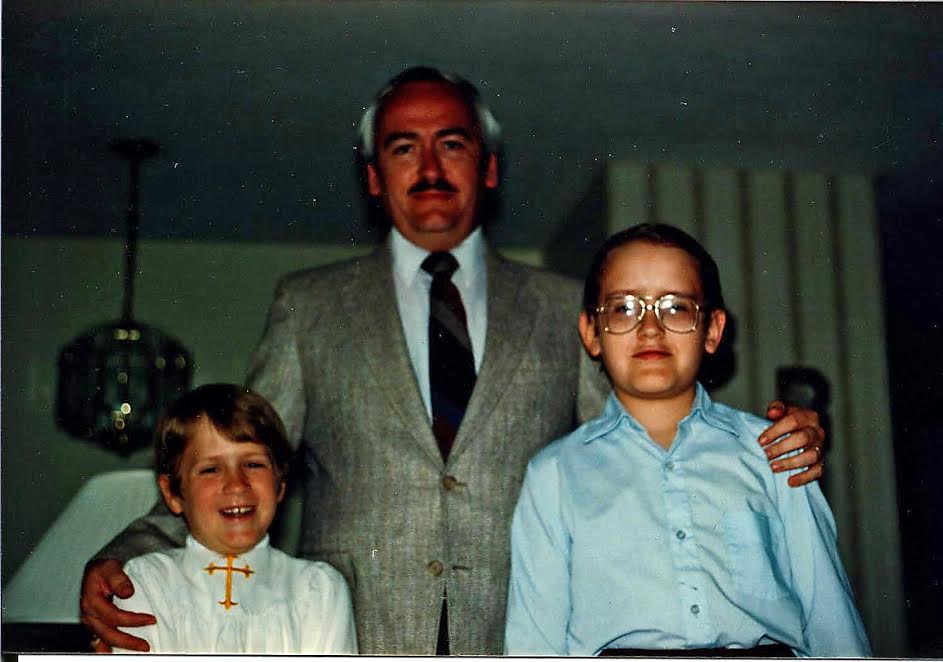

Ben Roy was 7-years-old when the abuse first took place at his Catholic summer camp.

He didn't tell his parents until years later. But no action was taken — until now.

Roy, a Denver comedian, spoke with CPR in 2018 about the abuse he endured at a New Hampshire summer camp run by the Diocese of Manchester called Camp Fatima.

He's part of a wave of survivors demanding acknowledgment in some form from the church of the abuse they endured.

For some survivors in Colorado, that means financial reparations. The state’s Catholic Church has paid out about a million dollars to nine survivors of abuse since the Jan. 31 deadline to submit claims.

The reparations are one of the few ways abuse survivors can pursue justice in Colorado if their abuse happened before the '90s, when the statute of limitations was much more limited.

But for survivors like Roy whose abuse occurred in other states, the windows are left open for decades, allowing criminal cases to be made.

Since his initial interview, Roy was contacted by the New Hampshire Attorney General and an investigation was opened.

He returned to Colorado Matters to talk about what it’s like to pursue legal action decades after abuse, and how the results might not be what survivors expect.

Interview Highlights

On what changed his mind about pursuing legal action:

“I think after talking to my wife and to a therapist and just looking at where we're at in the world right now, and this conversation is everywhere, that I think I felt like it was time to stand up for myself. That as we had talked about with my father on the initial interview, they, for reasons as we had discussed, not done anything about it. I felt that I've always had this feeling as if someone didn't stick up for me, and I felt like perhaps it was time that I was that person for myself.”

On what the first steps of an investigation look like for survivors:

“The investigator for the Attorney General put me in touch with Gilmanton PD. They reached out to me and set up a time for me to come in and give a statement of what had happened...They had me meet at a child advocacy center, which apparently is common. If the incident occurred when you were a child, they'll have you do your interview at a child advocacy center.

That's the hardest problem with being the victim of abuse as a child. Your anger is often pointed at yourself because of what you can't remember. I remember the events very vividly. They're seared in my brain. As far as names, that's difficult. There are parts of it that ended in blackness. There's no way. It just cuts off. There's no amount of saying it over and over again is going to bring some memory back.”

On how the process can be emotionally challenging:

“What I did not count on with that interview was the amount of emotion that poured out of me. I thought I would be fine. In fact, I didn't bring anybody with me. My mom wanted to come along as emotional support, and I was like, ‘No, no, no. I got this. I've told the story a number of times.’

I mean, even now everything tenses up. It gets into the pit of your stomach. Like tears well up in my eyes. I don't know why. It just is an emotion that comes out. It's anger, it's fear. I hadn't been that afraid in a long time.”

On the fear of coming forward:

“I mean part of it is I'm afraid, again, they're not going to believe me. I was afraid that no one else would come forward. I was afraid people would think that I'm doing this for attention. It's a huge step anytime you see somebody with a badge and with guns, and there's people from the Attorney General's office. They're watching in another room on closed-circuit TV.”

On where his case stands now

“The people that I was dealing with were extremely kind and heartfelt and listened to me and, I believe, took my concerns and my fears seriously. I think they're doing their due diligence. I think this is another story, once again, of time being the Catholic church's best friend. They are fully aware that the longer they draw this out on a lot of these situations, the harder and harder it gets for anybody to be able to receive absolution.”

On what will advance his case:

“I mean, the biggest roadblock that they've run into at this point is the fact that a lot of the kids that attended that camp were from out of state or out of the country, because Canada is so close. So they're just having trouble tracking them down with the lack of records.”

On why coming forward was so important:

“I'm trying to remind myself that I pursued this knowing full well that this was a very uphill battle and telling myself that, regardless of the outcome, at least I stood up for myself. And I would tell anybody out there that even if it's been a long time, to do it for yourself, to be the arms that you wrapped around yourself. You know what I mean? To stand up and to put yourself first when somebody may not have in the past. You can be that for yourself.”