Trucks come and go from the EVRAZ Rocky Mountain Steel mill, a massive facility south of Pueblo. One of the main products workers make here are casings used for oil and gas wells in Texas and North Dakota.

Production of the casings stopped last spring when the coronavirus pandemic and low oil prices halted new drilling. About 200 people were suddenly out of work, said Patrick Waldron, communications director for EVRAZ North America.

“We were essential workers,” said Renee Johnson, 63. “We had to be there every day, every day, every day and then all of a sudden we weren't, and now we've been off 10 months.”

Although Johnson is used to the boom-and-bust cycle of the oil and gas industry, she sees this extended furlough as part of a bigger shift: The country is moving away from fossil fuels.

As President Joe Biden acts on his promise to tackle climate change, all eyes are on the emissions created by the oil and gas industry.

Biden halted construction of the Keystone XL pipeline, suspended oil and gas leasing on federal lands and said he intends to ask Congress to stop subsidizing the fossil fuel industry. He is not alone: Car manufacturers have also pledged to stop making vehicles that run on gas.

Communities in transition

Caught in the middle are more than 30,000 Coloradans who work directly in the oil and gas sector and others in related fields, according to a recent report by the BlueGreen Alliance, an organization bridging labor unions and environmental organizations.

Experts predict a long decline for those fossil fuels, but workers in the industry want to ensure they are protected if their jobs are one day put at risk.

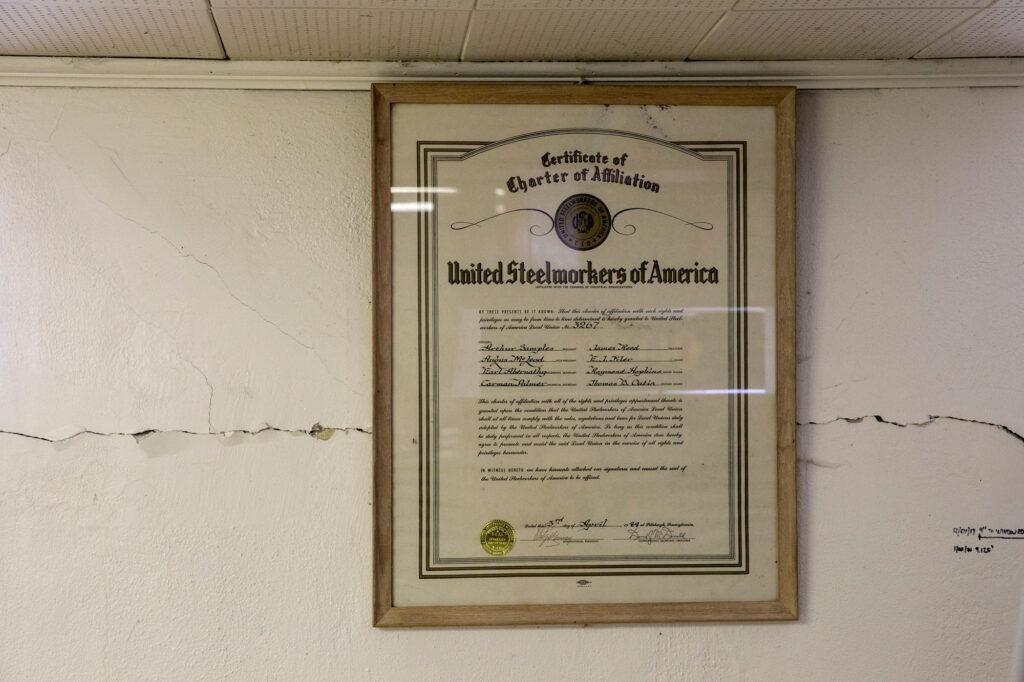

Charles Perko, an inspector at the steel mill and president of Steel Workers Local 3267, said it’s time for the state and federal government to think about transition plans for communities dependent on revenues from oil and gas production.

“There will come a time when something's going to affect the business where we won't come back,” Perko said. “And so we need to work very, very hard before the end to make sure those types of programs are in place.”

State legislators recently undertook a similar effort for coal workers as companies began to shut down mines and power plants. The Colorado Office of Just Transition was created in 2019, with legislators saying they had a “moral commitment to assist the workers and communities that have powered Colorado for generations.”

However, the office can’t expand to include oil and gas workers under the current legislation. Lawmakers and union leaders also say the office is underfunded, with about $160,000 allocated in last year’s budget.

“I don't think the Just Transition Office that we currently have is funded well enough, is in the right place to really make this commitment,” said Democratic state Sen. Kerry Donovan, who co-sponsored the bill that created the office.

The first step, Donovan said, is to talk to oil and gas workers to learn how such a transition would look. They could ask for job training centers, tourism destinations that bring in revenue, or broadband and rail to attract new industries.

Any solution would likely be expensive, said Gary Arnold, the business manager for Denver Pipefitters Local 208, who also sits on the state’s Air Quality Control Commission.

“All these programs are going to take resources, whether it be time or whether it be money,” he said. “In Colorado, I think our biggest challenge is we just don't have a lot of those additional resources available.”

Crisis and assistance

While Biden has promised millions of jobs would be created as the clean-energy sector expands, Arnold said they currently don’t pay as well as oil and gas jobs.

The federal government, Perko said, should help fund those changes through grants or other programs. It could help provide early retirement assistance or some form of additional income.

Biden says steps to curb climate change would include “helping revitalize the economies of coal, oil, and gas, and power plant communities.” His administration would look for grants and other programs to help, according to an executive order signed last month.

Given the severity of the climate crisis, there isn’t much time to waste, Perko said.

“This is a global emergency, it's something that needs to be done very, very soon,” he said. “If we can get a start on this today or tomorrow, really, to make sure that when it comes to the point where we can't wait anymore, that we have something else in place and ready to go.”

The steel mill should start to make oil-field well casings again in April, he said. Johnson said she is eager to get back to work after a year of being unemployed.

Oil and gas jobs won’t disappear before she retires, she said. But drilling also means work for Coloradans like her son, who also works at the steel mill. She thinks those younger workers will be able to make steel products for a new industry — or find different jobs.

“You hope it hangs in there for another 10 years or so, you know, for other people,” she said. “You don't want people to be out of jobs.”

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Joe Mazzocco's name in a photo caption.