Nine months of the pandemic had passed before a Durango area nursing home diagnosed its first case of COVID-19 last November.

It took just a couple of hours until it had its second.

From there the outbreak at Four Corners Health Care Center moved with astonishing speed.

There were 46 positive residents just more than a week later. Then 84 total cases the next.

Deaths followed. So many that La Plata County Coroner Jann Smith had to deploy a freezer truck to hold the bodies.

“We were going over there two, three, four times a day there for a little while,” she said. It was more bodies in a day than Smith would typically handle in a week.

By the time the COVID outbreak was over at Four Corners, 24 residents were dead.

The speed and severity of the COVID-19 spread at Four Corners was typical of the 189 outbreaks that swept through Colorado nursing homes between mid-October and early January.

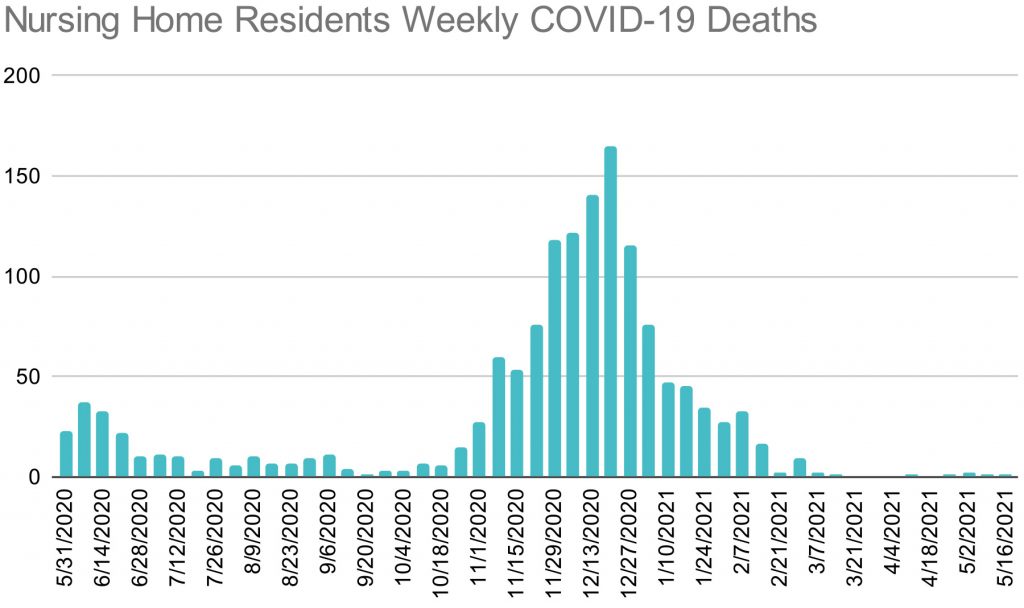

Colorado nursing homes reported 1,118 COVID-19 deaths between November and January to the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Between Thanksgiving and Christmas, Colorado had the worst rate of death per occupied nursing home bed in the U.S. It was twice the rate of death as the national average, according to the federal data.

Those deaths were driven by an inability to keep the virus out of nursing homes after the state’s system for testing and contact tracing in the homes collapsed.

Gov. Jared Polis and the leader of the state’s health department never revealed to the public that the state’s lab was overwhelmed or that the state’s nursing homes had become, however briefly, the deadliest in the nation.

They maintained that any shortcomings in the state’s performance against the virus resulted from personal choices made by Coloradans.

“We've worked very hard to put the right policies in place,” Polis said at an Oct. 6 press conference. “It's really up to people's behavior to maintain this progress in the coming weeks and months, we've surged our testing capacity … We've also implemented a world-class contact tracing ability.”

Within weeks, deficiencies in Colorado’s response were exposed by the third wave of the disease caused by the coronavirus. The systems Polis called “world class” left nursing home residents in what were perhaps the deadliest conditions in the nation.

Photo: The North Shore Health and Rehab Facility in Loveland, March 23, 2021.

Everyone who worked long hours for months at the state and local health departments did so with the intention of providing the best protection possible to Coloradans. The history of Colorado’s response to the global pandemic is not a story of widespread malfeasance or corruption.

It is instead a story of a lack of planning and preparation forcing difficult choices that went wrong. Even as vaccines have allowed millions to move beyond the pandemic, nursing home infections and deaths are back on the rise again in Colorado. As variants of the coronavirus proliferate, there remains a risk that one of them may mutate beyond the reach of current vaccines.

Knowing how Colorado fared compared to other states, and where the response fell short, can serve as a guide to preparations for a fourth wave if, or when, it arrives.

CPR reviewed thousands of pages of emails, documents and call transcripts, spoke with dozens of public health experts, and obtained video of meetings not open to the public to assemble a picture of the state’s preparations for and response to the third wave of COVID-19.

Among the findings:

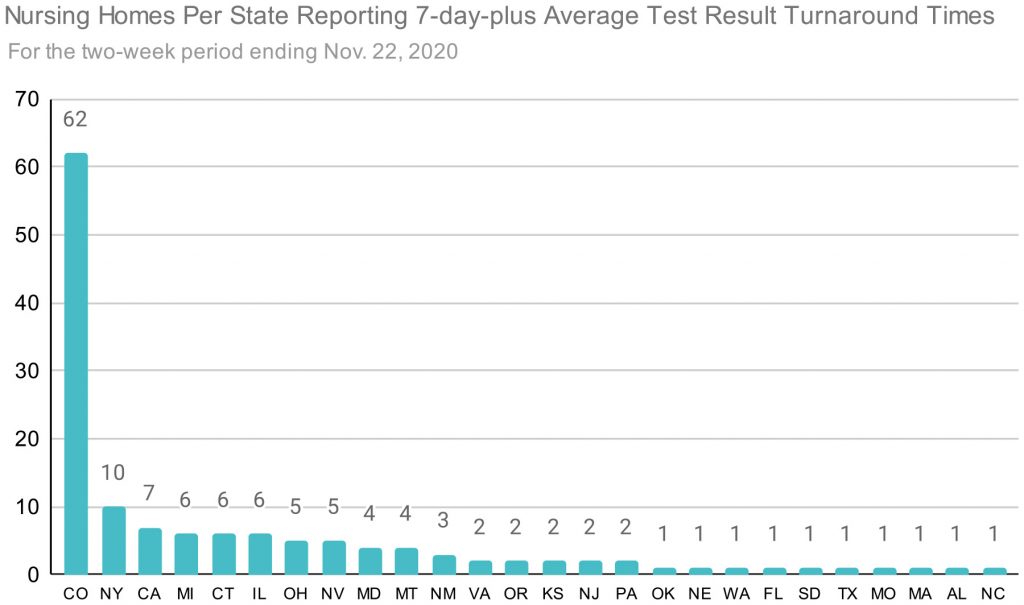

- Colorado’s state lab, run by CDPHE, was “largely maxed out” by Oct. 28, weeks before COVID cases would peak. The state lab handled testing for almost all Colorado nursing homes, and the state would go on to lead the nation, by far, in the number of nursing homes reporting seven-plus day test turnaround times.

- CDPHE reported that contact tracing was overwhelmed one week later on a call with county health agencies. That meant the state couldn’t properly warn contacts of those who were COVID positive.

- As these systems started to break down, county public health agencies begged Polis and CDPHE to order counties into stay-at-home. CDPHE was pushing for “gradual implementation of restrictions” even as the virus was spreading out of control. The state waited 15 days before increasing COVID restrictions, and outbreaks at nursing homes doubled in that time.

- Once the virus made it into nursing homes, the state’s “strike force” to combat nursing home outbreaks turned out to not be a strike force at all. It was a policy committee, with only one full time employee as of Oct. 21. The rest of the positions were vacant going into the deadliest phase of the pandemic. The strike force could only provide some limited staffing help for homes.

- In a desperate attempt to relieve pressure on the state lab, CDPHE entered into a no-bid contract with a start-up testing company called Curative, then began using it “off-label” to test even nursing home workers and residents without symptoms. The only cited evidence that gamble might pay off: a sampling of 14 test subjects by the company. The state eventually paid Curative nearly $90 million, but finally abandoned the test in January after two chaotic months.

Polis, through his press office, refused three separate requests from CPR News for an interview for this report.

In response to the last request, in mid-May, Polis’s communications director, Maria De Cambra, wrote that the governor would have little to add by answering questions about the state’s response to COVID-19 in nursing homes.

“We have made available all of the administration’s staff and leadership involved in Curative and our efforts to support nursing homes, I do not believe the governor would be able to provide any new information,” De Cambra wrote, offering to send a prepared quote rather than allowing the governor to be interviewed. “I hope you understand that we are still very much dealing with a pandemic and the Governor’s schedule is busy.”

CDPHE director Jill Hunsaker Ryan insisted that Colorado's handling of COVID has been a success.

“We think that we've been successful when you compare us to the United States on a whole,” said Ryan. “Our death rate compared to the U.S. … we've really knocked that down, and feel like we've been successful.”

Colorado’s rate of 117 deaths per 100,000 residents since the start of the pandemic does rank among the best 10 in the nation, well below the U.S. rate of 180, and far better than neighboring Arizona’s 244 or New Mexico’s 206, but worse than Utah’s 72, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It’s a considerable improvement from the first wave of the virus in the spring of 2020 when Colorado’s death rate ranked in the nation’s worst 15.

But where Colorado fell short is in its protection of nursing home residents. With little public attention, and no public acknowledgement by the state’s leaders, federal nursing home statistics show residents died in breathtaking numbers here throughout November, December and January.

November: 345

December: 543

January: 230

The deaths touched nearly every nursing home, large and small, and regardless of ownership. Nursing homes for military veterans mostly run by the state Department of Human Services had so many deaths that the state auditor has opened an investigation to determine why.

In an interview, Ryan said the state was not responsible. Though other states had managed to do a better job in protecting the vulnerable, in Colorado, the damage from the virus, in her view, was uncontrollable and could not be foreseen.

“Every nursing home death, every death from COVID-19, is tragic,” said Ryan. “We hadn't seen community transmission like this, not even in March. Like we hadn't envisioned that it could, the level could be that high.”

Many experts, however, had warned that levels of respiratory virus transmission would rise in cold weather. And the state had months to prepare throughout a relatively quiet summer. CDPHE received about $1.2 billion in federal funding last year for COVID response. More than half was spent on hiring contact tracers, staff for the state lab and making payments to testing contractors.

Polis boasted that Colorado was a “national model” when, on Nov. 2, he accepted a commendation from AARP Colorado for the state’s protection of nursing home residents. Bob Murphy, who gave Polis the recognition, was surprised by CPR’s findings.

“I may need to take a moment or two and recover from all of this that I've heard,” said Murphy.

Photo: Gov. Jared Polis provides updates on the state's coronavirus response efforts on Wednesday, March 11, 2020.

On Oct. 1, Lee Gonzales saw her husband of 40 years for the last time. Leo Gonzales was living at the Four Corners Health Care Center, a nursing home in Durango.

“In October, on my birthday, that's the last time I got to touch my husband and kissed him bye,” said Lee, becoming emotional.

She said the nursing home was mistreating him, and she didn’t like him being there, but she had no other options. Lee, who had her own health issues, couldn’t care for him anymore. Both of Leo’s legs had been amputated, because of complications from diabetes.

She had no idea just how dangerous it would be to stay in the facility.

Photo: Lillian "Lee" Gonzales holds one of her late husband's four accordions on Wednesday, May 26, 2021, at her home in Durango. Gonzales' husband, Leocario J. Gonzales, passed away while staying at the Four Corners Health Care Center.

Polis appeared to have no idea what was coming either. On Oct. 6, at his regular press conference he gave an update on the fires burning in Colorado’s mountains, then switched to coronavirus, where he made the boast about the state’s virus containment systems being “world class.”

“More of this is behind us than ahead of us,” Polis said at the time.

In fact, a wave of deaths was just around the corner. The weather was getting cooler, pushing people indoors, and cases were rising quickly.

About two weeks after Polis’s press conference, on Oct. 21, the Colorado School of Public Health wrote in a modeling report, “We are at a critical moment.” The next day Denver and Summit County tipped over an important benchmark: more than 350 COVID-19 cases per 100,000 people.

Four days later, on Oct. 25, the White House Coronavirus Task Force sent a status report to the Governor’s office, a service they provided to every state.

“At this point, the rapid increase in cases and test positivity in multiple counties and the severe situation in several adjoining states indicates that increasing mitigation measures should be done expeditiously to avoid falling behind the rapid spread,” reads the report.

Neither Polis, nor other state or local health officials, acted on the warning.

It was already too late for the state lab anyway. On Oct. 28, CDPHE held its regular conference call with local officials. In the last seven minutes of the meeting, CDPHE stunned the county health directors.

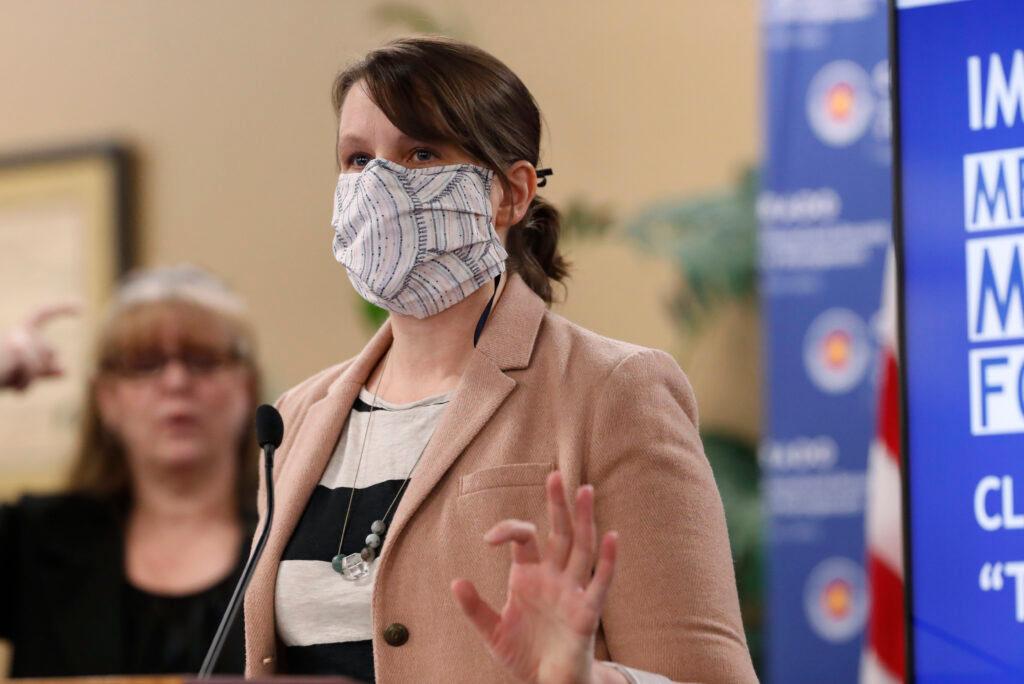

“We believe that we have largely maxed out our nasal swab, NP swab, PCR capacity,” said Sarah Tuneberg, the former testing and containment lead at CDPHE, according to a transcript of the call. She was describing various testing methods. (CPR’s attorney obtained the transcript after the state originally denied a request for the video recording.)

Tuneberg, who is no longer with CDPHE, said that they would prioritize high risk outbreaks at long-term care facilities, like nursing homes. But the state lab couldn’t handle anything else for the time being.

“It’s just sort of the way that this cookie’s going to crumble,” she told the county public health leaders. “I think we're in a place of like, ‘oh my God, so many people have COVID and so many people need testing.’ ”

Local public health directors were panicked.

On a separate conference call later that day, just between county public health directors, they were disturbed by all they had heard, the worst of which was crammed into the end of a long meeting.

“I'll just say that for me personally, I'm worried for our state,” said Joni Reynolds, the Gunnison County Public Health director. “I’m worried about how decisions are being made and what process is being used to make those decisions.”

Reynolds, who had appeared at press conferences with Ryan and was viewed as an ally at the state health department, complained that the state and local public health were still, eight months into the pandemic, not operating as a system.

“And frankly, I'm concerned about whether they have the leadership capacity to think in a solid way to make the best decisions for our state.”

Photo: Gov. Jared Polis speaks during a press conference May 20, 2020.

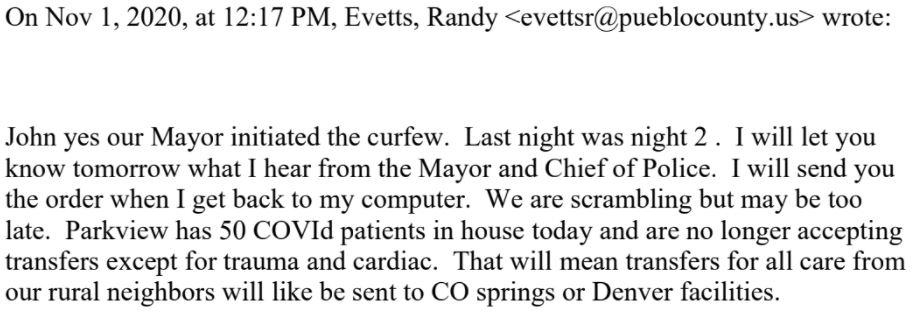

Meanwhile, the virus continued to spread across Colorado, and local public health directors were grasping for answers, short of issuing their own stay-at-home orders. The county directors considered that step to be politically impossible. On Nov. 1, Dr. John Douglas, the director of Tri-County Public Health, asked his colleague in Pueblo how the city curfew was working.

“We are scrambling but may be too late,” Randy Evetts, the Pueblo County Public Health director, responded. “Parkview [Medical Center] has 50 COVId [sic] patients in house today and are no longer accepting transfers except for trauma and cardiac.”

Three days later, CDPHE held its regular Wednesday meeting with local public health, where the state relayed more alarming news.

“We have exceeded our contact tracing capacity in the state,” State Epidemiologist Rachel Herlihy said, according to a transcript of the Nov. 4 call. “We're probably reaching about half of our cases right now with contact tracing, meaning that a number of those individuals who've had contact with a case may not realize because they're not being notified by public health they had a potential exposure and need to be in quarantine.”

That same day, CDPHE sent a letter, signed by Ryan, to Jefferson County officials -- one that many large counties received around this time -- telling them the county qualified for a stay-at-home order, or the so-called “red” level on the state’s COVID restriction dial.

But instead of imposing such an order, Ryan wrote, "we have decided that a gradual implementation of restrictions is suitable at this time.”

The next day, on Nov. 5, Colorado’s county public health directors sent a letter to Polis’s office and CDPHE asking them to move counties into red level restrictions now.

CPR was first to report the letter back in November. But emails from county directors to the state that day show just how concerned local directors were.

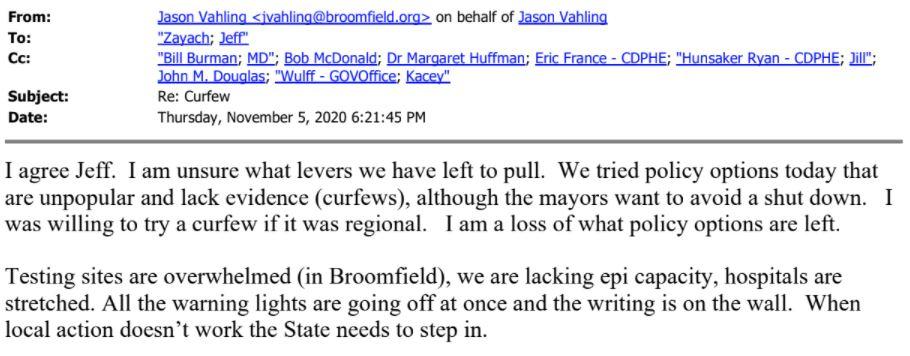

Jeff Zayach in Boulder wrote, “I think we have lost control of the virus.”

“We will need to have CDPHE use the Dial to put our counties into Stay at Home if we don’t want to see our rates get to North Dakota levels in a few weeks,” added Douglas at Tri-County.

“All the warning lights are going off at once and the writing is on the wall,” wrote Jason Vahling, the Broomfield County public health director. “When local action doesn’t work the State needs to step in.”

However, 15 days would pass until Nov. 20, when Polis put 15 counties into what they called "red-plus" level restrictions. In that time the governor’s office and CDPHE had created a new color on the dial, called "purple," that was the new shutdown color. "Red-plus" would close things like indoor dining, which studies show is among the largest spreaders of COVID-19.

Photo: A sign on Berthoud Pass reminds travelers to please wear a face mask on Thursday, Oct. 22, 2020.

Ryan, the CDPHE director, told CPR that Polis was concerned about the economic impact of moving counties into “stay-at-home.”

“The Governor was very concerned about level red and it being a stay-at-home order,” said Ryan. “So we were trying to figure out how do you avoid just social and economic calamity?”

Evaluating the effectiveness of pandemic restrictions is difficult. Some of the places with the highest death rates per 100,000 residents, like New York and New Jersey, were also some of the first to institute strict “stay-at-home” orders or mask requirements. But they are also among the most densely populated states.

Some of the less-populated places with top 10 high death rates during the pandemic, like Mississippi, Alabama and South Dakota, were resistant to instituting strict social distancing measures.

Though research continues, experts in public health say shutdown policies have been proven to work in extreme cases. Colorado was in an extreme situation. And not shutting down sooner allowed the virus to spread, creating fear, which also hurt the economy.

“You’ve got to do this in order to save lives,” said Tamara Konetzka, professor at the University of Chicago in public health sciences. “And I don't know why they didn't do it. This part of it to me in terms of explaining more nursing home cases and deaths is actually much more important than the testing, despite the problems with those policies. This is really the key.”

In an interview, Douglas acknowledged that shutting down the economy again would have been painful. As a society we’ve never had the discussion about how many deaths are worth how much economic fallout, he added.

“But yes, I think if we'd moved to red (level) sooner, we would have had fewer people get sick and fewer people getting sick means fewer people die,” Douglas said.

In the days while Polis waited to act, the number of outbreaks at nursing homes nearly doubled from 38 active outbreaks on Nov. 4 to 71 on Nov. 25.

And by the week ending Nov. 22, Colorado’s nursing homes led the nation in a dubious category: the state had, by far, the largest number of nursing homes in the U.S. waiting more than seven days to get test results, according to data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

The slow turnaround times meant that infected people tested by the state lab, including those working in nursing homes, could spread the virus for days before knowing they had COVID-19. Many of those people worked shifts at multiple nursing homes, further creating the opportunity for the virus to spread while waiting for results.

Still, red-plus level worked. Cases began to decline. But it was too late to prevent spread through dozens of nursing homes - and for the governor himself.

Five days after moving counties, on Nov. 25, Polis went into quarantine because he was exposed to someone who was COVID-positive. Three days later, on Nov. 28, his office confirmed that he and his partner Marlon Reis had contracted COVID-19.

Photo: Closed businesses in downtown Greeley, Dec. 21, 2020.

The state lab also had an outbreak of COVID-19 among its staff. The long turnaround times for test results rendered the tests meaningless. So, exercising emergency authority to select vendors without competitive bidding, CDPHE switched nursing home testing to Curative, a Southern California-based company that had started operations only months prior.

It is run by a 20-something-year-old college dropout and had been focused on sepsis testing until the pandemic presented a global need for COVID-19 testing. Unlike most other COVID-19 tests using the best technology, it is saliva-based, which theoretically should make it easier to administer. But within weeks of the Curative rollout, complaints began arriving at CDPHE about the accuracy of the tests.

On Nov. 27, just a few days into Curative testing, Joyce Humiston, who runs seven nursing homes across southern Colorado, said the tests were returning false positive results.

“We are seeing a troubling trend with the new state mandated Curative testing system,” Humiston wrote to a group of nursing homes, associations, local public health and CDPHE. “We have now had staff who tested positive up to 4 weeks ago in 3 different facilities who has since tested negative several times with us .....coming back positive with Curative.

“I think something is flawed with the Curative system.”

Three days after Humiston raised concerns about Curative, Tuneberg, the head of testing at CDPHE, wrote back, on Nov. 30, that Curative is not required by the state (they could use a different lab if they wanted to pay for it themselves), and “Curative uses the gold standard PCR processing and we have not observed anything funky to date.”

Curative, like the state lab, was provided to nursing homes free of charge, and so only a few homes used a different lab.

Tuneberg wrote the test had emergency use authorization (EUA) from FDA, but that was only half true. The FDA had only approved Curative for testing of people showing symptoms of COVID-19 like fever or cough. State Epidemiologist Herlihy authorized nursing homes to use Curative “off-label” on asymptomatic nursing home patients and employees.

Curative had provided data on 14 asymptomatic patients at the time of the decision.

“But even with that 14, felt comfortable moving ahead with use of Curative in asymptomatic individuals,” said Herlihy back on Oct. 28, during a conference call with local public health officials.

In an interview, Herlihy disputed that the decision was based on just 14 patients.

“So we received additional information from Curative after that,” said Herlihy. “They provided that additional information to us where they had a broader set of data that I think was data, an evaluation they had done, I want to say in San Antonio, Texas. So it was additional data. It wasn't just 14 patients.”

Still, it’s clear from the transcripts that Herlihy and CDPHE had made their initial decision based on 14 patients. Experts think this was a bad idea. Professor Konetzka said: “I don't know that anybody wants to do anything based on 14 patients. Right?”

Dr. Gregory Gahm, the top doctor at Vivage Senior Living, the largest chain of homes in Colorado, was also concerned, and tried to get state leaders to change course. “I mean, to me, the biggest red flag was the EUA didn't cover what we were doing,” Gahm said in an interview.

“I know that I was carrying the banner saying, ‘we shouldn't be here. This is just wrong,’” said Gahm, who tried for weeks to arrange a call with CDPHE officials to discuss the problems. “And that kept getting put off for weeks and weeks and weeks. And in the middle, [CDPHE’s] answer was to call Curative. And they said, ‘Oh, trust us. It works.’”

Curative would not agree to an interview.

Tuneberg also wrote to Humiston on Nov. 30 that Curative is a “well respected national lab,” though many public health experts had never heard of them, they were not included in a list of vendors vetted by the national nursing home association, and Curative had only started testing on a large scale eight months earlier.

Email discussions around this time between Tuneberg and Herlihy and Emily Travanty, the state lab director, were heavily redacted by the state before they were provided to CPR News.

But the emails show that Herlihy and others at CDPHE were aware nursing homes were having problems with false positives.

One official who did not appear to know was CDPHE executive director Ryan.

“False positives are much, much less common … we didn't hear reports of that, but I don't think we would refute if nursing homes said they did,” said Ryan in an interview.

And Ryan and the state’s chief medical officer Eric France were not involved in selecting Curative in the first place, according to Tuneberg.

“I would say that it was a three-way decision between me, Dr. Travanty and Dr. Herlihy. And the three of us together did very robust evaluations of a ton of vendors.”

Photo: Workers set up for the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment first community testing center for COVID-19 at the state lab on March 11, 2020 in Denver.

Emails reviewed by CPR News make clear that, even after months of being deluged by offers from companies selling tests, treatments and personal protective equipment, the state did not have a formalized process for vetting Curative’s offer even as they negotiated a multi-million-dollar contract with the company.

Herlihy, a medical doctor with responsibility for tracking the virus and its evolution in the state, was making calls herself to people who had used Curative and were suggested as references by the company.

“Of particular value are their rapid turn-around time…” wrote Alexander Lazar, a professor of pathology at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, in an email that was forwarded to Herlihy. Lazar wrote that he “helped to oversee and medically authorize over 1 million COVID PCR tests in Texas.” He said Curative was a “solid partner.”

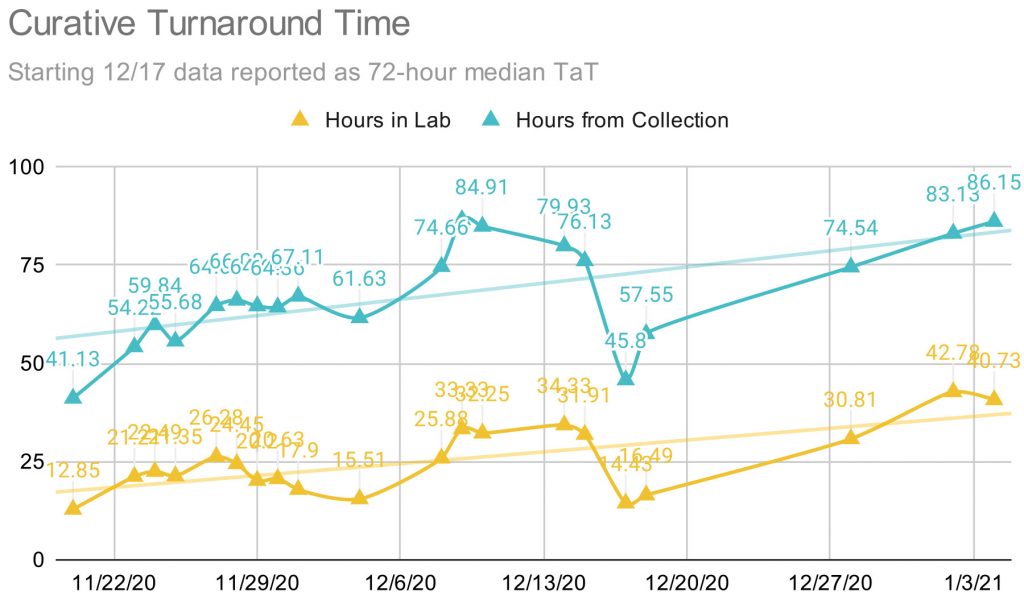

Curative’s contract in Colorado called for 48-hour turnaround times. “To ensure successful expansion and execution of community testing efforts, the contractor agrees to, in good faith, allocate processing capacity daily for the State to achieve a 48-hour turnaround to results notification at a performance rate no less than 90%.”

But the company appears to have met that goal on only a couple of days, according to a slide in a CDPHE presentation.

The state was made aware of the long processing times as early as Dec. 6, when CDPHE received an email from Four Corners nursing home concerned by the slow turnaround.

“Our tests from Friday were delivered on Saturday but have yet to be checked in for testing. At this rate we may not get them back before we test again Tuesday. I'm sure Curative is being hammered, but just wanted to let you know,” wrote Christy Bradley, the administrator at Four Corners to CDPHE and the local public health authority.

On Dec. 9, Tuneberg acknowledged the long turnaround times in an email: “Curative is swiftly increasing their personal [sic] and capacity at labs, and also investing in automation solutions to improve efficiency and processing times. It is anticipated that turnaround times will be reduced in the near future to more acceptable levels.”

Two days later, on Dec. 11, Peter Myers, who runs CDPHE’s strike force for nursing homes, said in a presentation to long-term care facilities, that “Curative has snagged here recently...it's certainly not acceptable for that to happen, and we need that information as quickly as we can absolutely get it,” said Myers. “They're using, I think, some additional robots to help do some of these things. In order to get those turnaround times down.”

Whatever Curative did worked, but only for about a week. Turnaround times briefly fell to less than 48 hours in mid-December, but then quickly grew again, almost doubling by January.

After weeks of tamping down concerns about Curative, the state was rocked by a new development.

Photo: Colorado State Epidemiologist Dr. Rachel Herlihy arrives at a press conference in March led by Gov. Jared Polis, where he addressed the state’s progress in combating the spread of the coronavirus.

On Jan. 4, the FDA issued a warning that Curative, used off-label for asymptomatic testing, as Colorado was doing, ran the risk of producing false negative results.

“Risks to a patient of a false negative result include: delayed or lack of supportive treatment, lack of monitoring of infected individuals and their household or other close contacts for symptoms resulting in increased risk of spread of COVID-19 within the community, or other unintended adverse events,” reads the safety communication.

Now, in addition to slow processing times that allowed workers or residents with COVID-19 to continue spreading it through the facility, and complaints about false-positive test results that required nursing homes to quarantine healthy workers, resulting in staff shortages, there was also reason to worry that nursing home workers who tested negative, actually carried COVID-19.

On Jan. 8, Dr. Gahm, with Vivage Senior Living, wrote to CDPHE leaders that he knew they were now “working feverishly to do everything we can to move forward and quickly distance ourselves from Curative Labs…Curative sold us a bill of goods.”

The state continued to use the test.

“The initial report is that this issue is related to collection techniques and not necessarily to the test itself,” said CDPHE’s Myers, on a Jan. 8 webinar presentation to long-term care facilities. “So I'm not a scientist, but I'll give a general layperson's description of what's going on: the thought is that there's simply not enough material on the swab when it is sent in. So if there is a positive test, there's not enough material to then trigger that as a positive test. And so it comes back negative.”

“Nothing changes with Curative in the meantime, continue to test as you're instructed,” added Myers.

Gahm wasn’t buying it, and he sent a follow up email the next week, with reporting he’d done on numerous instances of false positive results across nursing homes, making a case for the state to drop the company.

He included an email from a doctor at Columbine Health Systems, that runs a number of long-term care facilities:

“After reviewing some charts, I also have examples of what were likely false positive residents,” wrote Dr. Rebecca Jackson in the email. “This of course is more concerning as they are transferred to the COVID units. It is devastating to think of the morbidity, and potentially mortality, occurring across the state because we were told to trust the test and that a ‘positive is a positive’”

Finally on Jan. 21, 17 days after the FDA warned about Curative, Tuneberg wrote in a mass email, “based on guidance from FDA, CDPHE is discontinuing Curative testing for residential care facilities and other congregate settings. We are working with all residential care facilities and other congregate care settings that are currently using Curative to transition to other labs. We do not anticipate any gaps in testing access.”

Later that day, she resigned her full-time role, though she would remain for a time in a part-time position.

The state paid Curative a total of $89,265,675.

Did the switch to Curative have any bearing on an increase in infections in nursing homes? It is impossible to independently track. Contact tracing had collapsed under the weight of the increase in cases, and, because of patient confidentiality, the source of individual nursing home infections remains unknown.

After an initial interview for this story in February, CDPHE assembled statistics showing that in the early parts of the third wave, nursing homes that didn’t use Curative had an even higher rate of infections and deaths than those that did. That flipped in January, but the reasons are not known, and the state declined to provide the data they relied upon to CPR News.

Even the exact number of nursing home residents who died in the third wave is unknown. Relying on reports directly from nursing homes -- which CPR found overcounted deaths in some homes -- the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reports 1,118 nursing home residents in Colorado died between November and January.

CDPHE, however, reports that 951 died in outbreaks that started between October and January. CDPHE doesn’t report the exact date when residents died, just the total number and when the outbreak started and ended. CPR also found CDPHE’s data was at odds with the federal data, undercounting and overcounting deaths in some facilities as compared to the nursing home reports.

Death certificates are confidential in Colorado, making it impossible to independently determine which is correct.

What is known is that the loss of the state lab, followed by the introduction and then loss of Curative, left nursing homes in the lurch. In many cases it was weeks before other labs could pick up testing.

Curative would not agree to an interview, but the company sent a statement:

“In the Safety Communication, the FDA reiterated the need to use Curative’s kit strictly in accordance with its label instructions and test people within 14 days of symptoms onset. The test performance and labeling, however, have not changed, nor has the company observed any changes in test performance. [emphasis added by Curative] We have been working with the agency to address their concerns and these limitations, and we will continue to work interactively with FDA...”

Six months later, the FDA has not changed its position on Curative.

“No further information has been published regarding the Curative SARS-Cov-2 Assay real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test, so it appears that the safety communication Risk of False Results with the Curative SARS-Cov-2 Test for COVID-19: FDA Safety Communication is still in effect,” the agency wrote in response to questions from CPR News. “The FDA will keep the public informed if significant new information becomes available.”

Polis and state public health leaders had assured Coloradans that everything possible was being done to help nursing homes once the virus was inside. In a Nov. 2 press release, Polis promoted the state’s “strike force” as a “national model.”

As soon as an outbreak was confirmed by Four Corners, the local public health authority connected the nursing home with CDPHE, so the publicized “strike force” could go into the nursing home and take charge of a rapidly deteriorating situation.

“And then every day the numbers just kept going up,” said Liane Jollon, the executive director for San Juan Basin Public Health. Her team was in tears as the outbreak grew. It was the first at a nursing home for them. Durango is a small city, and many people in the public health department had some personal connection to the facility.

“Finally, it was like, ‘Hey, help me to understand why are these numbers going up so fast when they have every resource available to them?’ And then the answers were ‘well, no, they don't have that resource.’”

Because it didn’t exist, at least not in the way many in public health envisioned it as an infection control SWAT team that would put boots on the ground to help nursing homes in crisis, without issuing citations and seeking fines.

According to email records, the best the nursing home was going to get from CDPHE was a trio of low level epidemiologists with minimal experience in outbreaks.

They held virtual meetings with the facility, but more was needed.

“I was trying to understand by asking the team, you know, call back CDPHE, get an explanation of the strike force,” said Jollon. “Why isn't it on the ground yet? Why haven't we stemmed infection? Why is infection still spreading?

“So there was a lot of confusion, there was a lot of chaos,” said Jollon. “Cases were rising fast. We were as a team working through nine other outbreaks at that time.”

That’s about the time Jollon and her team came to the realization that there was no rapid response strike force. CDPHE told them that the strike force can help, but only in supplying some additional staffing, but the nursing home said they didn’t need it.

Peter Myers, the strike force lead for CDPHE, left a voicemail with Jollon’s team on Dec. 10 saying they have already contacted the nursing home about staffing. “Looks like they're in pretty good shape as of now,” said Myers.

Photo: Gov. Jared Polis watches as Denver Mayor Michael Hancock provides an update on coronavirus in Colorado on Tuesday, Nov. 17, 2020.

The “force” in strike force implies more than one person, but Myers was listed as the only staffer of the strike force, according to an Oct. 21 organization chart.

Myers told CPR News that others from CDPHE and the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy & Financing were contributing to the strike force throughout this time, but he was busy hiring the rest of the positions as the state was swamped with cases.

“We were bringing on additional staff, which is, you know, challenging for me personally, getting new staff up and running while continuing to do the work,” said Myers. “But I think we made it through pretty well.”

And he was clear that the strike force wasn’t really a strike force.

“The strike team’s more of a policy group than that kind of rapid response, with the exception of staffing, we do have resources for facilities for staffing,” Myers said.

That was not what the local public health believed it to be. “We 100 percent thought it was a rapid response team,” said Jollon.

That’s because that is how it was portrayed.

“We assembled the residential care strike team in late April,” said Polis at a July 23 press conference. “It's hard work. It's hands-on work. It's taxing mentally and physically. We know it's hard on everybody, but it's really important work. And I want to thank those that are doing it.”

The name alone was confusing.

“Nothing in that name sounds like a policy group. This is sort of tracking right back to the heartbreak that we all felt every day in December,” said Jollon.

Other states did it differently.

After Massachusetts nursing homes endured a horrific death rate in the first wave of the pandemic, elected leaders there demanded changes. A task force was formed to determine what went wrong and how to prevent it from happening again.

The state created a $130 million incentive last April for nursing homes to improve infection control and staffing. They gave the homes money to hire their own testing services to prevent the virus from getting into the homes again. Nursing home directors there credit the state with working in partnership to make the homes better, rather than issuing fines to achieve compliance.

Nursing homes “are threatened by anybody walking in with a pad and a pencil, taking notes on what's wrong,” said Dr. Lew Lipsitz, with Hebrew SeniorLife in Massachusetts.

Massachusetts created a true strike force, providing boots-on-the-ground experts to go into nursing homes and help teach and make changes without fear of fines or closure.

“So it was very important that these consultants come in, in such a way, that they were aligned with the nursing facility, they were there to help,” Lipsitz said. “They were not going to report this to anybody else. They really had to develop very quickly this kind of collaborative feeling of trust.”

The difference between the two states’ performance in the third wave is dramatic. Massachusetts homes had just 25 percent of the death rate of Colorado homes in December.

Maryland also created a true strike force, said a representative of SavaSeniorCare, which owns the Four Corners nursing home in Durango. SavaSeniorCare runs facilities across the U.S.

“I know in the state of Maryland they had a strike team and we used them the way they should have been used … a real strike team,” said Annaliese Impink, a vice president ot SavaSeniorCare.

Maryland had a COVID-19 death rate in nursing homes less than half Colorado’s at the worst of the third wave in December.

The nursing home industry in Colorado said the state supplied only $14.7 million in COVID relief money for infection control and prevention as their bed census was falling and costs for things like personal protective equipment was rising.

Colorado then fined nursing homes $4.7 million for infractions such as a staff member wearing a mask below their nose.

The punitive approach was not welcomed by nursing home operators.

“The state takes pride in saying they collected $5 million in fines,” said Jay Moskowitz, CEO of Vivage Senior Living, the largest nursing home operator in Colorado. “That's an embarrassment because the truth of the matter is, you know what? We were begging for more education, more training, more oversight, helping us don't come in and cite us because the mask is below the nose.”

And the punitive approach clearly didn’t reduce the death rate in Colorado facilities.

On Dec. 15, Lee Gonzales got a call out of the blue from a nurse at Four Corners.

“And he told me, ‘Mrs. Gonzales, um, Leo just passed away,’ and I go, what?! I cannot. What!? I mean, I was in shock.”

Leo was among 24 people who died in the outbreak. SavaSeniorCare, which owns the home, wouldn’t share details surrounding how Leo got COVID, or the circumstances of how he died, with CPR. Lee Gonzales doesn’t know either.

“I have no idea,” said Gonzales. “I just have a grim bleak picture of how he died.”

Photo: The ashes of Lillian "Lee" Gonzales' husband, Leocario J Gonzales, sit on a shelf in her home in Durango, Colorado, on Wednesday, May 26, 2021.

Is Colorado ready for a fourth wave?

In May, blues singer/songwriter Nathaniel Rateliff was recruited by the governor’s office to present an award to the state workers who led the state’s nursing home “strike force” strategy.

“It is my great pleasure to introduce the winners of the 2020 outstanding innovation in government award to the leaders of the residential care strike team,” Rateliff said in a video posted to Polis’s Facebook page. “Their management of complex, multi-department cooperation serves as a national model of effective governing practices.”

The award coincided with yet another increase in the rates of both infections and deaths among Colorado nursing home residents. The numbers remain small, but in May of this year they were double the national average and they make clear that the pandemic is not over for unvaccinated Colorado seniors.

The problem, according to statistics compiled by AARP, is the large number of infections among nursing home staff. Last month, there were 2.4 confirmed COVID-19 cases among nursing home staff for every 100 residents. That’s three times the national average.

Staffer infections could also be contributing to Colorado’s above-average rate of nursing homes reporting staff shortages, which stood at 28.9 percent in May, the most recent figures available.

No state has been perfect in its response to the still-evolving coronavirus, but from the start, Colorado’s effort has regularly stumbled and been riddled with inconsistencies.

Ryan was slow to recognize the seriousness of the virus even before the first case was diagnosed here, telling the state board of public health that she expected it would be like a “bad seasonal flu.” Little was done to prepare for the arrival of the virus, leading to a shortage of personal protective equipment in hospitals and nursing homes and regular communication breakdowns between the counties and the state.

In May, 2020, Colorado was the only state that ranked in the nation’s bottom 15 in population density to appear in the top 15 in the rate of COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 residents.

The state lab was a constant source of frustration in the early days of the pandemic, with turnaround times of up to 10 days, rendering test results useless. But when Polis sought to fix it, he initially brought in a well-intentioned email entrepreneur to scale up testing, even though the entrepreneur acknowledged publicly “I don’t know what the f--- I’m doing.”

Polis, who took credit for slowing the first wave in the state by closing bars just before St. Patrick’s Day in 2020, waited weeks to take any action that could harm the economy in the fall as local public health directors implored him to re-institute restrictions.

Though the state has never acknowledged shortcomings in its COVID-19 response and Polis refused to answer questions about why he believed a contact tracing program on the brink of collapse was “world class” or an unstaffed policy program mislabeled as a strike force was a “national model,” there are small signs that the state is preparing this time in case of a surge by a coronavirus variant.

The state department of Health Care Policy & Financing recently announced that nursing homes would soon receive another $16 million “to support continued infection prevention efforts and rising costs of direct care staffing.”

The “strike force” now has employees, and the state lab has a new director. CDPHE has added daily antigen testing of unvaccinated nursing home staff in addition to twice weekly PCR testing.

Mako Medical, a North Carolina company founded in 2014 which has contracts with the CDC and states across the nation, now has the contract to do nursing home testing in Colorado.

But the deaths in the third wave were likely preventable, said Bob Murphy of AARP, who awarded Polis the commendation for the state’s protection of nursing home residents last fall just before the dam burst and the state led the nation in resident deaths.

That was before Murphy knew how badly the state’s seniors would fare in the third wave. Murphy said that by fall of last year the way the virus spreads was well known and prevention strategies had been proven.

“It's tragic and somebody needs to be accountable,” Murphy said.

This story has been updated to correct the amount Colorado provided nursing homes for infection control and prevention to $14.7 million. An initial version of the story contained a larger figure. The story has also been edited to clarify that Sarah Tuneberg left her full-time position with the state on Jan. 21 but remained in a part-time role for a time after that date.

"How Colorado Caught COVID" is brought to you by Colorado Public Radio's Investigations Team. Help make more accountability journalism projects possible with a gift today.