It was just 11 days into the coronavirus crisis and Colorado’s testing labs were overwhelmed. Gov. Jared Polis needed help.

“We are doing our best to be one of the leading states, if not the leading state for testing,” Polis said on March 16. “But scaling that up has been very frustrating.”

Just before that news conference, Polis forwarded a memo detailing “mass testing limitations” to the former CEO of an email marketing company in New York City, asking him to come to Colorado and help solve the testing riddle.

“That’s a long list of bottlenecks,” Matt Blumberg wrote back while preparing to travel to Denver. “No tests, no one to test, and no lab to process results.”

Polis responded: “Yeah but other than that, it’s easy-peezy.”

There was one other problem: Blumberg had no experience in public health.

“I don’t know what the f--- I’m doing,” Blumberg texted to Brad Feld, a Boulder venture capitalist who connected Blumberg and Polis. “Fortunately, I never have, and that’s usually OK.”

Not this time.

Today Colorado ranks at or near the bottom of states in testing for COVID-19. Even as Texas and California have experienced resurgences of the virus, Colorado also still has the third-highest rate of COVID-19 deaths among states west of the Mississippi.

The lack of testing has made it difficult or impossible to track the progression of the disease in Colorado and to protect vulnerable populations, like nursing home residents, by requiring widespread testing of caregivers and other front-line workers.

It began with a failure at the federal level to produce enough test kits in the early days of the pandemic. That was followed by a decision by the White House to push responsibility for testing and protective supplies on to the states. That put Polis at the center of a fast-moving crisis with difficult questions and few answers.

Rather than relying solely on the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, or the nation’s public health infrastructure, where experts have been researching, discussing and training to respond to a pandemic for years, Polis turned to people outside of government, from his familiar worlds of technology and entrepreneurship.

At the same time Polis turned to Blumberg, who volunteered his time and paid his expenses, Colorado’s statewide public health agency was losing key staff and leaving critical positions unfilled, or turning to people with limited public health experience.

In addition to reviewing emails obtained in response to open records requests from CPR News and Columbia University's Brown Institute for Media Innovation, CPR News conducted more than two dozen interviews of state and county public health directors and other experts in public health to understand what was happening inside Colorado's early response to COVID-19.

An Exodus Of Expertise

CDPHE leadership has been partially hollowed out by a series of high-level departures, forcing those left behind to take on new and unfamiliar responsibilities, replacing people with years of experience.

The agency has lost its former interim director, who ran the massive organization for months before current executive director Jill Hunsaker Ryan was hired. The state lab lost its experienced full-time director. The disaster response division lost its logistics expert. Trained epidemiologists, including CDPHE’s highest-ranking physician, left. The points of contact between the state and county health departments were gone.

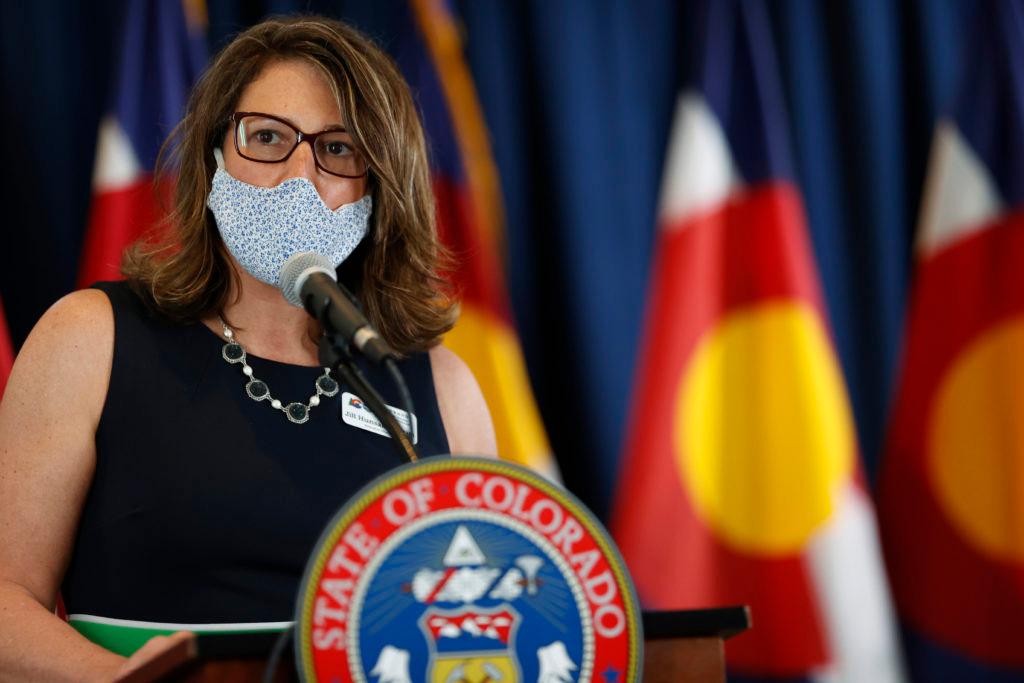

“I would say in general our response to the epidemic has not been affected by some people leaving the department,” said Ryan in an interview with CPR News. “The proof's really in the pudding. Colorado has one of the lower incidence rates in the nation. And I think that's because of good advice, using data, and being really methodical both in our initial policies and in relaxing our restrictions.”

A week later, Polis said at a press conference that “We are losing right now in Colorado.”

Since then, Polis has declared the state to be “on the knife’s edge” with a growing number of infections and hospitalizations along with an increasing rate of positive tests. He issued a mandatory statewide mask order he had previously declined to impose, saying it was preferable to closing the economy again.

Polis’ communications office declined multiple requests from CPR News over the course of a month to interview the governor for this story.

Ryan minimized the impact of the departures at CDPHE, saying she was unfamiliar with some of the names on a list of ex-employees provided to her by CPR News, though all of them were in positions of responsibility within her department.

“A lot of the people on this list that have the name ‘epidemiologist’ behind them, I don't know them and I don't know why they left,” Ryan said.

Personnel issues had been building since shortly after Ryan was appointed executive director of CDPHE. The former Eagle County Public Health director, and county commissioner, had initially been appointed by Polis to a transition committee to find a new CDPHE head. Then he offered her the job.

Nine months into her tenure, Polis’s administration was alerted to trouble at the department through an anonymous email on Nov. 18, 2019.

The warning was signed by “A concerned group of CDPHE employees” and outlined in detail a “brain drain” underway at the state’s health department.

“We have some grave concerns with our current Executive Director, Jill Ryan. She had very little management or true executive-level experience prior to coming to CDPHE, and is quite clearly overwhelmed in her role,” reads the email sent to Polis’ chief of staff Lisa Kaufmann and Tony Gherardini, then the governor’s director of operations and cabinet affairs.

“She seems unable to absorb the vast amounts of information required in this role … The agency has reached a point of paralysis, where staff are confused and directionless, and partners are often left hanging.”

The email details the departure of three key staffers, all in the months before COVID-19: Tista Ghosh, a nationally recognized epidemiologist, an expert in vaccine delivery, and the state’s chief medical officer; Erin Ulric, interim director of the Prevention Services Division; and Anne-Marie Braga, a 14-year veteran of the department and the chief point of contact with county public health directors.

The governor’s office briefly looked into the claims in the email but was satisfied that it was probably from a disgruntled employee upset about financial reforms Ryan was pushing in the disease division.

The exodus would only get worse.

CPR News has learned of at least nine other high-level departures from CDPHE, many with disease and disaster response experience, in the months before, and after, the first case of COVID-19 was announced on March 5. Five of the public health leaders have left in the last six weeks, including Tony Cappello, the former head of CDPHE’s disease control and public health response division and the original COVID-19 incident commander. Cappello claims in a recently filed lawsuit against the department that he was pushed out.

All were contacted by CPR News. Of those who responded, only Cappello would comment.

“It’s a difficult time,” said Cappello in an interview with CPR News. “There’s really good staff at CDPHE. There are a lot of people who really have a passion for what they do, that’s why we go into public health. This is what we live for, situations like this, so it is a shame.”

Cappello was shown the email that warned Ryan was unqualified and micromanages the agency, leading to a brain drain.

“I think it's fair … this is the sentiment that we've heard amongst my staff when I was there,” said Cappello. He said it’s not fair, however, to lay the blame for everything at Ryan’s feet, but “the responsibility is always with the executive director.”

“And when you have such high-level epidemiologists who are not there, I think it's difficult to ensure that protection for the community,” Cappello said.

Ryan said there were inaccuracies in the email, but didn’t elaborate. She also said that one of the people listed in the brain drain got a promotion to a job elsewhere and that Ryan wrote the letter of recommendation.

“Of course I'm always disappointed to hear negative feedback. And I take feedback very seriously,” she said. “But as you say, it is an anonymous email.”

Polis’ office declined repeated requests for an interview with the governor, who has appeared alone at most of the state’s briefings as the public face of Colorado’s response. In answering written questions from CPR News, a spokesman said the departures have made no difference.

“CDPHE has over 1,400 employees, so 12 employees represents less than one percent of the workforce,” said Polis spokesman Conor Cahill. “Turnover, after a new administration is elected, is not only expected, it’s often healthy for the organization to have a fresh start.”

Six of the 12 have left just since the first case of COVID-19 was diagnosed in Colorado, and these positions were near the highest levels in the department.

The departures were bound to create challenges for the state’s response to the disease, said Glen Mays, professor and chair at the Colorado School of Public Health.

“Just the sheer number of senior positions, and the kinds of specialized expertise they bring to bear, it's a definite loss for the agency in terms of overall immunological expertise and experience in managing large scale public health emergencies,” Mays said. “It's significant to lose this kind of expertise in a single state agency in a relatively brief time period in the midst of continued response,” he added.

County public health directors have felt the departures. Dr. John Douglas, the director of Tri-County Public Health said “the state has not had enough bandwidth to help respond to the public health epidemic” and that’s “undoubtedly” related to the loss of leadership at CDPHE.

But Douglas added that the problems at the state are magnified by an “abdication of federal leadership that led the state having to carry the load. I think it was further exacerbated by the politicization of so much of the epidemic, and I lay a lot of that at the feet of the federal government.”

The departure of Cappello, then CDPHE’s top epidemiologist, was particularly acrimonious.

Cappello claims in his lawsuit in state court that he was the victim of “retaliation” for trying to clean up “unlawful” expenditures in the agency’s STI/HIV branch, which manages infectious diseases.

His lawsuit against CDPHE and Bob Bongiovanni, who had been the deputy of the STI/HIV branch chief, alleges that Bongiovanni used his “personal relationship” with Ryan to leverage attacks against Cappello because Cappello had raised concerns about Bongiovanni’s spending of HIV prevention funds.

“CDPHE, with the active encouragement and involvement of Mr. Bongiovanni, retaliated against Dr. Cappello by methodically stripping away his responsibilities and eventually terminating his employment,” reads the lawsuit.

Bongiovanni retired from the state in 2017. He now operates a small business called Keota Consulting, which he said consults with states on best practices.

“The claims made against me are completely inaccurate. I've dedicated my life to doing the right thing for the HIV community,” wrote Bongiovanni in a statement to CPR News.

As the pandemic spread in those first weeks of March, according to Cappello’s lawsuit, “CDPHE began excluding Dr. Cappello — its highest ranking epidemiologist — from critical functions associated with the COVID-19 Pandemic Response on account of his disclosure of information.”

“That's simply not true,” said Ryan. She insisted that Cappello made the decision to move Scott Bookman into the COVID-19 incident command role before leaving the agency. “And I have text messages from Tony when he told me that he had provided the incident command role to Bookman. I would dispute those claims, and I can't talk about specifics of the litigation.”

By June, Cappello had been fired, according to his lawsuit.

Cappello’s deputy in the disease division, Dan Shodell, also left the department in June.

“Events over the past year have created a hostile work environment that seems destined to result in Dr. Shodell’s resignation or termination,” according to a demand letter from Shodell’s attorney addressed to Ryan at CDPHE on Feb 10. “The principle perpetrator of these events is former Department employee and current outside consultant Bob Bongiovanni, who has received both explicit and implicit support from Department leadership.”

Shodell settled with the state and signed a non-disclosure, non-disparagement agreement. He said in a statement that he left the agency in June. He received a payment from the state of $47,655 “which represents disputed wages” plus a $5,000 payment to his legal counsel, according to the agreement.

An internal audit of the branch was released in late May. It identified $4.58 million in “questionable costs,” (though the audit report said the amount was likely higher) and made 56 recommendations for changes to record-keeping and fiscal management. “Overall we found that oversight was inadequate and that some funds were not expended appropriately.”

As Cappello and Shodell were on their way out, Bookman, the director of the state lab at CDPHE and a former paramedic, was put in charge of managing the global pandemic for the agency.

Bookman is well-regarded at CDPHE and with some in local public health. He was formerly the chief paramedic for Denver Health.

But Bookman is not a disease expert, a doctor nor an epidemiologist. And his promotion would leave the state lab facing a transition in its day-to-day management just as the nationwide competition for testing supplies and lab capacity ballooned in the early days of the crisis.

Ryan argued that Bookman was a logical choice for incident command since he held a “master’s degree in incident command and homeland security.”

In a statement, Bookman said the lab has continued to run smoothly and he has been able to manage both it and the overall state response.

“The state lab has an incredibly dedicated staff and incredible leadership team,” Bookman said. “As I moved into the incident commander role, I had a clear line of sight to the lab and was able to work with my team there to build our testing program despite numerous challenges associated with the way in which COVID testing was rolled out by the CDC and FDA and the crippling supply chain shortages.”

“He’s an entrepreneur”

By March 15, ten days after the first case, the state lab was overwhelmed and Ryan emailed a memo to Polis detailing the problems.

“Subject: Memo Regarding Mass Testing Limitations at the State Lab…” It listed among other things: problems with CDC kits, a lack of supplies and a lack of testing equipment.

Private labs weren’t doing much better. “Lab Corp recently put a hold on processing more lab tests. CDPHE has not been able to find any other labs in the nation to take the backlog of tests,” Ryan wrote Polis.

A day later, on March 16, Polis forwarded that email to Blumberg, the tech executive. “We need a strategy in each area,” Polis added.

“That's definitely concerning,” said Mays, from the Colorado School of Public Health, in an interview with CPR News. “I think it partly reflects an overly optimistic view of what technology alone can give us without the requisite expertise and experience about how to apply it.”

Ryan was not copied on the emails between Polis and Blumberg, inviting him to Colorado. But she said in an interview that Polis was trying anything to improve the state’s performance.

“He's an entrepreneur and he wanted to surround himself with innovators and people with business minds,” Ryan said of Polis’s decision to bring in Blumberg. “I think that he just wanted to make sure he left no stone unturned in mounting this response.”

Blumberg was between jobs when he agreed to helm the Innovation Response Team. He had recently left the company he founded 20 years ago, Return Path. It specializes in email marketing, and Blumberg wrote a book on startups. He doesn’t have any medical or public health or disaster response experience.

But within days of his arrival, after he was recommended to Polis by fellow Boulder tech entrepreneur Brad Feld, there was Blumberg, standing behind Polis at a press conference.

Blumberg, a New Yorker, wrote a half a dozen blog posts about his time in Colorado. He wrote on March 17, his first day, that it was still unclear what exactly he was doing there. “My charter and structure are a little fuzzy, guess that’s why I’m here to figure that out.”

He wrote in his blog about just how disorienting it was to be thrust into the state’s emergency operations center. His first day on the job, he reported getting “Lots of ‘Sorry, who are you and why are you here?’”

In a later interview with CPR News Blumberg said: “Our marching order on day one was really two things: figure out how to scale testing programs.” And “provide services to people who are in some form of isolation or quarantine.”

The same day Blumberg was meeting everyone in the state emergency operations center for the first time, hospitals were in full-blown crisis because of a lack of testing, and Polis was resisting calls to shut down the economy and order Coloradans to stay at home.

Elizabeth Concordia, president and CEO of UCHealth, wrote an email to Polis on behalf of Colorado’s major hospital providers.

“I am writing to ask for very specific and needed help for all of these front-line providers — we have the same urgent issues,” she wrote on March 17.

The problem was getting test results: “We are waiting days for these results. We are wasting personal protective equipment (PPE) because we have to treat all of these patients as though they are COVID-19 positive when, in fact, many may not be.”

Concordia concluded her email asking for help in procuring testing reagents and more PPE. “Our staffs are exhausted and should not need to worry that we cannot protect them or that they have to reuse equipment. This is not right and certainly not fair to our front-line workers,” she wrote.

In addition to helping conserve needed protective equipment, testing also gives health officials and epidemiologists an idea of how much the virus is spreading through a community, and where. Polis has regularly lamented the lack of data available to him in making decisions about whether to open or close the state’s economy.

Though Polis was quick to bring Blumberg on board and charge him with building a mass testing program, Colorado, while facing the same problems with the federal government like every other state, has struggled more than others to get enough test equipment and to make testing as widely accessible to residents.

Comparing state testing efforts is tricky. There is no federal requirement for standardized reporting. Some states, like Colorado, report the number of people tested by a diagnostic test designed to uncover active infections. Others include the number of tests administered — not people — and tests for antibodies, not infections, have to be teased out of the data to get an accurate comparison.

CPR News examined available data from all 50 states and the District of Columbia to arrive at the best possible comparison. As of the numbers available Sunday morning, Colorado ranks last — 21st of 21 — in the number of people tested per 100,000 residents among all states and the District of Columbia that report tests the same way Colorado does.

Colorado recently also started reporting the total number of tests administered, which accounts for people who have received multiple tests. The state testing effort fares slightly better by that measurement. As of Sunday morning’s reports, Colorado ranks 27th of 31 states using that reporting method.

By any measure, Colorado has fallen behind.

For example, Wisconsin, which has a similar population to Colorado and counts its number of tests administered just as CDPHE does, has, as of Sunday morning, tested 369,163 more people than Colorado.

That difference gives Wisconsin a more accurate picture of the virus’ spread and allows them to better prepare for a possible second wave.

As of late last week, Wisconsin’s lab capacity for daily tests is 24,156. On Colorado’s best single testing day, July 24, the state reported almost 8,000 fewer than that.

Wisconsin tested more than 14,000 people in a day three times last week. Colorado just crossed that threshold for the first time Friday.

The governor’s office said that Blumberg had other responsibilities besides testing, and was also in charge of procuring testing supplies.

“To be clear, Matt Blumberg was not solely in charge of testing,” wrote the governor’s office in a written response to CPR News’ questions. “[CDPHE incident commander] Scott Bookman, in fact, is responsible for the trailblazing work that was done in the early days of the pandemic standing up the first in the nation drive through testing sites, that ultimately had to be curtailed due to ongoing supply issues.”

The statement from the governor’s office continues: “Colorado has been aggressive in our efforts to scale up testing, acquire supplies in the globally competitive market and to stand up testing sites across our state.”

Today, cases are up, hospitalizations have grown, it can take a week or more to get test results and Colorado remains well behind other states in tests administered each day, not closing the gap.

“The turnaround time on the testing samples is taking way too long,” said Jeff Zayak, director of Boulder County Public Health. “It makes it much more difficult to do effective and timely contact tracing and follow up. And that is not something that we can control at the local level.”

He added that results need to get out in one to two days to be effective.

Still, Colorado has so far managed to keep the rate of infections well below that in some neighboring states, and the number of deaths per day has dropped from a peak of 37 per day on three days in April, to an average of three per day in July.

Despite a methodical approach some county health officials find frustrating, public health officials give Polis credit for emphasizing the benefits of masks early in the pandemic compared to some other governors and for ordering the closure of bars just before St. Patrick’s Day and July 4, likely reducing some spread of the virus in crowds.

The number of tests administered each day has been growing in July, and Polis said last week that testing volume will continue to improve with more supplies on the way.

But it’s not likely to be fast enough to catch up to other states.

Harvard researchers recommend states conduct at least 45 tests per month for every 1,000 residents. That works out to 8,700 per day in Colorado, a figure Polis said Colorado would be able to hit routinely in June. Colorado has only met that goal on 16 distinct days — all in July — in the nearly five months since the pandemic began.

Nothing Blumberg or, his replacement, Sarah Tuneberg, have tried compared to the widely available, fast, free drive-through and walk-up testing available in some other states. Colorado’s drive-through sites were popular but of limited scale. The National Guard was brought in to test at nursing homes and in some other sites, but that effort was widely scattered.

The state’s busiest testing site is run not by CDPHE, but by the City and County of Denver. At times, the single site, which offers up to 2,000 tests per day, has been responsible for as much as a third of the tests administered in the state on any given day. The state has provided about five days’ worth of testing materials, but the site is run by Denver.

It could close as soon as of the end of July, though Denver is in talks with the state to find a way to keep it open.

As he waited in his sweltering car recently to get tested, Armando Geneyro, a freelance photographer, was surprised that Colorado would have less per capita testing than Wyoming and Alaska.

“I feel like we need to step it up, no?” he said. “We definitely need to step it up.”

That’s not how Blumberg felt as he left his volunteer effort in Colorado on March 27.

“Deep deep dive on Mass Testing — so good to spend that time,” he wrote in his blog. “Pretty much got the strategy right — shocking we could get that close with so little public health experience.”

Read Part 2: As a potential second wave of infections approaches, state and county public health officials remain at odds over roles and approach