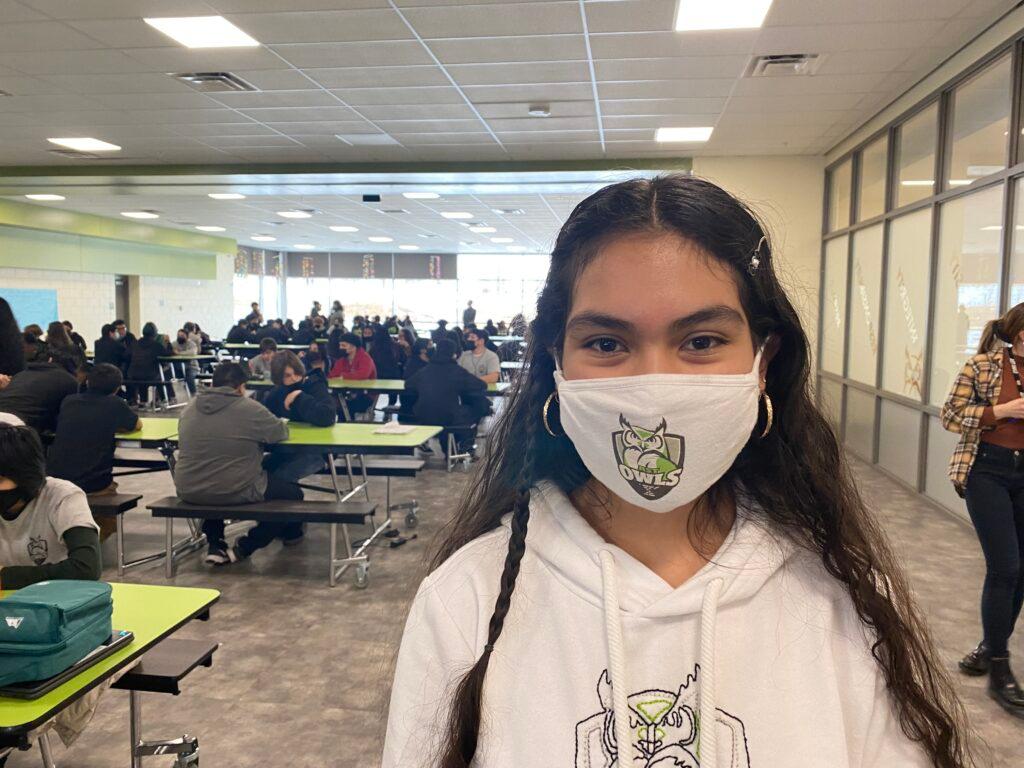

It’s lunch at Aurora Science and Technology Middle School, and student Fatima Najar reflects on life in pandemic times. “Yeah, it's been pretty hard, pretty difficult,” she said.

Last year, the virus cost her and her classmates many months of learning in person. This year is better. Everyone is back and wearing masks.

“It's different, I think, than any other middle school experience. But we're pushing through COVID,” Najar said.

Pushing through COVID-19 is the new focus for many people in Colorado, let alone these students. As the pandemic enters its third year, which one could call COVID-22, the “new normal” — at least so far — involves figuring out how to live alongside this virus.

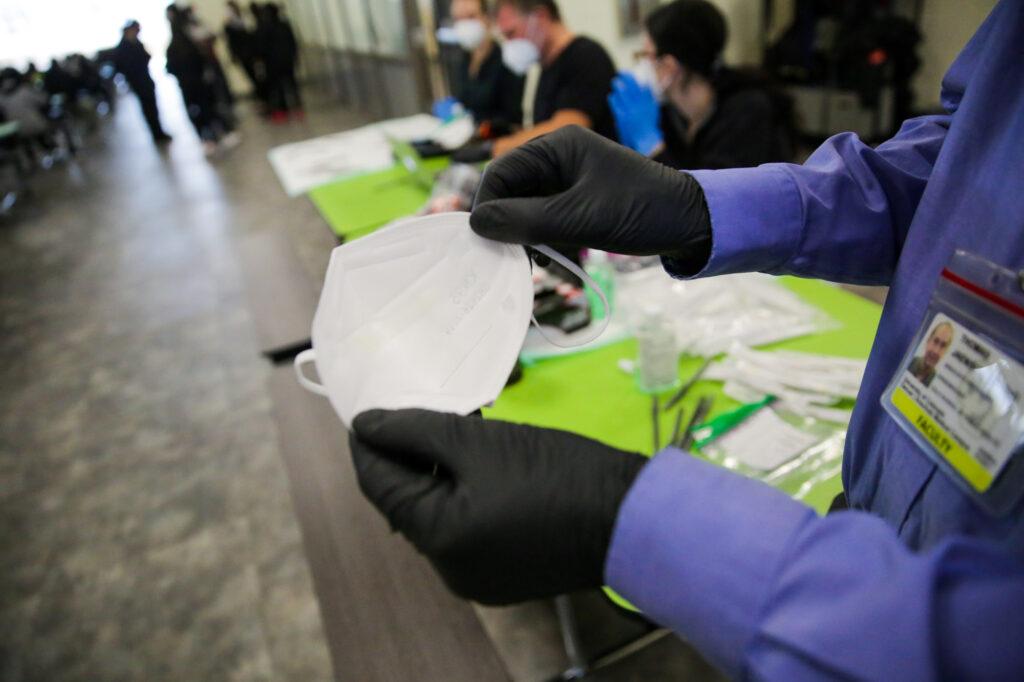

And for this school, living with COVID-19 now includes something new. Najar is one of dozens of students who volunteered for a pilot project. On their lunch break, they visit tables in the corner of the school’s lunchroom, where researchers do nasal swabs on the students and enter information into laptops.

The month-long program offers the 435 kids at this school weekly diagnostic PCR testing, through COVIDCheck Colorado and a partner company, Summit Biolabs. It gives them and their parents a much quicker turnaround time on results, usually a day or so.

School director Rebecca Bloch said it gives peace of mind to staff and families.

“Knowing that there's testing at school helps keep that layer of safety,” Bloch said, who added that “almost all of the people who we have identified as testing positive have been asymptomatic.”

To track all kinds of cases, researchers are also studying another innovation: new poly-vinyl alcohol strips that fit inside masks. The strips trap kids’ exhaled breath and can then be tested, says CU Anschutz Dr. Thomas Jaenisch.

“Maybe there will be a rapid test where you can stick the mask strip into a tube and then shake it. And then it turns green or red. And then you can base a decision on that,” Jaenisch said. “We are far from that, but that's our vision.”

Dealing with the 'ups and downs'

Helping people know their status more easily and quickly will be one key to dealing with COVID-19 in the third year, said epidemiologist and clinical professor May Chu from the Colorado School of Public Health.

She said the coming phase will involve “learning to deal with the ups and downs of transmission in the community because another variant will come.”

Even as scientists keep learning more, the state government is preparing to pivot to the next phase, whatever that may be.

“It has obviously been an incredibly difficult two years, and we all want to move on with our lives,” said Scott Bookman, the state’s incident commander. The state has put out an RFP, a request for proposal, to plan a transition from pandemic to endemic.

“We are looking at short term and longer-term scenarios, and starting to do some planning around how do you live with this virus in more of an endemic environment,” Bookman said.

The proposal, which anticipates the contract starting as soon as Feb. 15, asks a series of questions, for example these regarding public health: What are the triggers for an emergency response should it be necessary to protect hospital capacity in the future and what does that look like? Are workforce gaps going to hamper our ability to move to an endemic response this summer? (e.g. local public health, hospital and medical, long-term care facilities, etc.) What functions are currently done by local public health that they will no longer continue?

Planning ahead now, for a next big wave, makes a lot of sense, said Chu.

“Cautious optimism, that we can use this period to better prepare for the next wave, is I think the right message,” she said.

But she said a disease outbreak won’t become endemic until it becomes predictable. And until society achieves much lower transmission levels, that won’t happen.

“We’re not there yet,” Chu said.

That shift from pandemic to endemic, she said, hopefully, comes with community immunity provided by vaccines and prior infections.

“True definition of endemic is that it's predictable and repeatable and cyclical or seasonal, in that sense. And you expect it at a certain time,” she said. “We're far from that at this point.”

On the horizon, in the short run: more immune population and calls to prepare

The staggering speed and spread of the super-infectious omicron variant scrambled the outlook of the pandemic, at least for now, both nationally and in Colorado.

“I think we're all adjusting,” said Dr. John Swartzberg, a clinical professor emeritus and expert in infectious diseases at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health.

The omicron wave started to slam Colorado around Christmas, right on the heels of the delta variant, which hit hard in late fall.

On Jan. 11, the positivity rate, the rate of positive tests, a reliable gauge of transmission, nearly blew through 30 percent in the state. It was a pandemic record and about five times what it was about a month earlier. Daily cases nearly hit almost 20,000 on Jan, 6; that was about triple the previous pandemic high number for a single day. Hospitalizations of confirmed COVID-19 patients from the omicron wave peaked at 1,676 on Jan. 18, within 200 of the all-time coronavirus high about two years earlier. In January, those infections resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Coloradans.

Hospitals faced the wave just as a chronic staffing shortage and tight intensive care capacity grew worse.

But the wave has fallen just as fast as it had spiked. By this week, metrics were still relatively high but much improved. The positivity rate Wednesday dropped below 11 percent and confirmed COVID-19 hospitalizations declined to 861, still elevated almost half what they were three weeks earlier.

The improving situation is one of the reasons given by local officials for counties lifting both indoor mask mandates and mandates in schools.

No one is making predictions, but with the falling number of cases driving infections, combined with folks who are already vaccinated, may provide a bit of a breather, at least in the short run.

“It’s actually not all bad news,” said Swartzberg. “We're going to have a much more immune population by the spring, actually by March, a much more immune population. And that's gonna make a difference when a new variant comes along.”

He said other advances are anticipated, like ramped up production of monoclonal antibodies treatments and oral medications that work against existing virus strains.

The hope is that those fully vaccinated and boosted will be well protected, and the unvaccinated who get severely sick will have access to life-saving treatments.

“The pandemic's gonna look very different to us in a much better way in late spring and summer,” he said. “That’s my guess.”

Planning ahead for whatever comes next

If a break of sorts is on the horizon, now is the time to be planning ahead for the next troubling variant, through all sorts of prevention measures, including the already familiar ones, vaccination, masking, distancing ventilation, surveillance, testing and more.

“If people really are serious about having an endemic relationship with SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) that's gonna require investment in infrastructure. It's gonna require investment in testing and public health,” said Samuel Scarpino, a complex systems scientist and the Managing Director of Pathogen Surveillance at The Rockefeller Foundation. “Otherwise what we're saying is that we're just gonna accept 500,000 deaths a year. I'm not willing to do that.”

He said federal and state lawmakers need to prepare and now.

“It's time for them to act and to move money around, to prepare for what we know will come in the future,”Scarpino said.

Even with omicron now waning, the virus is still out there, spreading and mutating and spinning off new variants, making for an uncertain future, he said. “We need to invest for the next one that's coming.”

And that planning means figuring out how to bolster a battered health care workforce.

Last week, UCHealth, one of Colorado’s biggest systems, with 27,000 employees, launched a new $35-$50 million dollar program to help with staffing shortages by funding educational opportunities for its workers.

Health care workers, especially in hospitals and long-term care, are beyond exhausted and that needs to be addressed, said Colleen Casper, executive director of the Colorado Nurses Association. For weeks, about half the state hospitals said they anticipated a staffing shortage, a situation that’s only now starting to improve slightly.

“Imagine you're at the bedside every day for the last two years, three, four, five days a weeks,” said Casper. “They're worn out, and their capacity to deliver care is compromised on every level.”

The new phase, with a focus on schools

Chu said in this new phase of the pandemic, learning how to detect cases and keep kids in schools is important, since they are critical vectors for spread. That’s why the U.S. government started a school Test to Stay program, which Colorado is now rolling out too.

Angel Avery likes the project at her son’s school.

“He’s here, I don't have to go out of my way to get” him tested, she said. “It's just kind of being proactive because we have asymptomatic people running around. I was asymptomatic.”

Avery’s husband and others at the car repair shop where he works all tested positive around Thanksgiving. His case was mild. Then she tested positive. Their two kids didn’t catch it. Avery’s son, Dane, a basketball-loving seventh-grader, volunteered for the school’s testing program.

“If it comes back negative, then I know that I won't will most likely not be spreading it to anybody else,” Dane said.

That includes his friends “especially one of my other friends, that I think one of the siblings has something with their immune system.”

Eight-grader Fatima Najar agreed with that sentiment. Plus she said, “I actually really enjoy it because I feel way safer.”

Far from a burden, Najar sees it as just what needs to be done for now, another chapter of coping with COVID-19.

What to know about COVID, testing, masks and more in Colorado right now:

- BIG PICTURE: Omicron COVID cases are falling in Colorado. What that means for hospitals, masking and life

- J&J VACCINES: If you got the Johnson & Johnson vaccine, you should get a booster shot. Here’s why

- COLLEGE BOOSTERS: These are the Colorado colleges and universities requiring booster shots for faculty, students and staff

- HOW TO USE AT-HOME TESTS: At home rapid COVID tests: how to use them and why they may mislead you if you don’t have symptoms

- REPORTING AT-HOME TESTS: If you take an at-home COVID test and it’s positive, you’re supposed to report it to Colorado officials. Here’s how

- WHERE TO GET A BOOSTER: Here’s where you can get a COVID booster shot and test in Colorado