The radio version of this story originally aired on NPR's Here and Now.

Grant Johnson’s dream is to have tens of thousands of people yelling and cursing at him every day.

Right now, he only has a few people yelling and cursing at him.

“I can’t imagine what it would be like once the stands are filled and to have all those people yelling at you,” says Johnson, as he stands along the third base line of Coors Field, flush with a dreamy grin as his eyes circle the ballpark.

The 20-year-old Johnson umpires high school baseball games in his hometown of Little Rock, Arkansas. But his dream is to work in the big leagues.

“It’s what I want to do for my job every day is to be out on these fields. I would love to do that,” Johnson said. “And you have not just a couple parents with their kids, you would have grown adults yelling at you and thousands of other grown adults. It’s gonna be completely different, but I'm excited for it!”

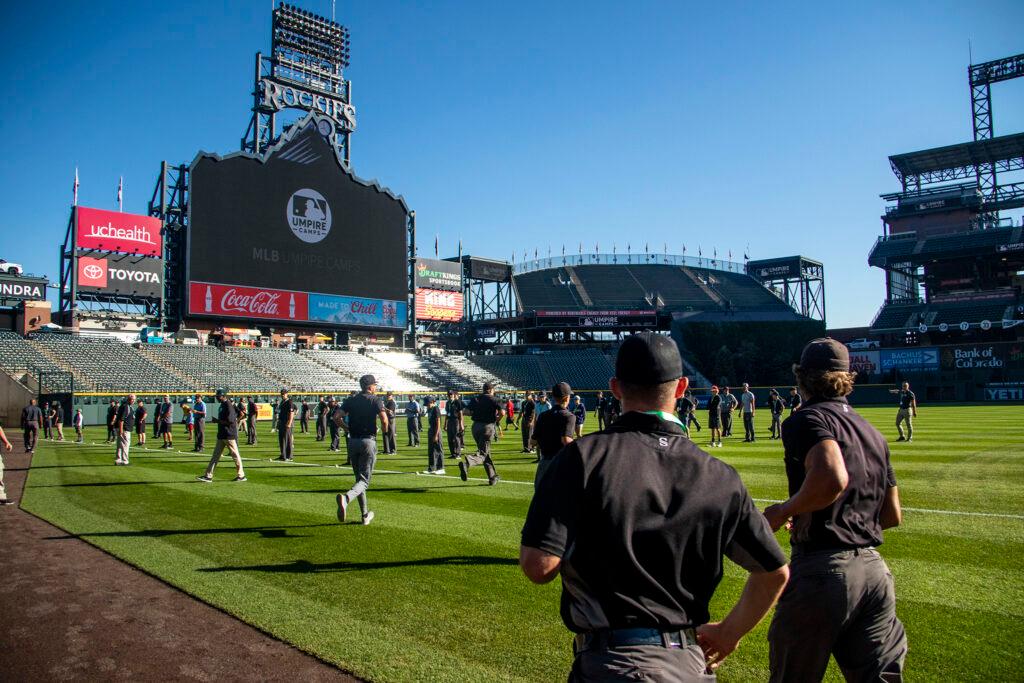

Johnson, along with more than a hundred other would-be Major League Baseball umpires, were in Denver recently for a league-backed clinic, where they received free training from former MLB umpires. The league holds a handful of events like these every summer to try to get more amateur umpires on the professional baseball path.

But, gosh, being an umpire is a tough job.

At the big league level, umpires work alongside some of the most rich and famous athletes in the world – but no one is lining up to get their autograph. They work long hours in the hot summer sun, often while getting booed and yelled at. They’re baseball fans’ favorite punching bags.

And like any job, you don’t start at the top. To get there, you likely have to start working Little League and high school games – where fan behavior can be … the worst.

“Parents yell at you, call you whatever they want because they don’t care,” Johnson said. “At the end of the day, they’re not gonna see you. They let their mind free and their tongue loose and just say what they want.”

Johnson recalled an incident where a parent was cursing at him over some of his calls — in a game being played by 11-year-old kids. Johnson ejected the parent, which led to more cursing.

“It's tough hearing it, but over time, I've learned how to just take it,” he said. “It’s just as if someone was talking mean to me online: It's not gonna affect me; don't lose any sleep. So I just let it go.”

Youth baseball umpires say parents are at the top of the list when it comes to bad behavior during games.

“There seems to be a flaw within the actual understanding of the rules of the game,” said Scott Altman of Morrison, a youth baseball umpire. “Most people see a lot of calls made on TV, which may not apply to Little League the same way they’re applied to Major League Baseball.”

And when coaches, parents and fans don’t like a call, they’re not shy about voicing their discontent, which is totally understandable, umpires say. But that discontent crosses a line when it leads to verbal abuse and violence.

And bad behavior makes headlines. A few years ago in Lakewood, a fight broke out among parents who were angry over a call made by a 13-year-old umpire, in a game where the players were just 7 years old. And earlier this year in Abilene, Texas, an umpire had to go to the hospital after a coach shoved him to the ground during a game.

“I just think we’ve become a brasher, louder, less-civil society, and it plays out at sporting events,” said Barry Mano, president of the National Association of Sports Officials. “I mean, we are getting a report at the NASO, a report of a physical assault almost daily. That was unheard of before.”

Mano says sports leagues across the country were already dealing with a referee/umpire shortage even before the pandemic, as many baseball umpires and football and basketball referees were quitting over low pay and bad treatment by coaches and fans. Now, as games have returned after a pandemic pause, Mano says about 25 percent of the officials who were working before the pause have not returned.

“And it just takes away from the joy of these kids trying to play a friggin’ game,” said Dale Scott, a retired Major League Baseball umpire. “And one of the reasons we’re so short on officials is the older guys are retiring. Leaving the field, and we are not getting that recruitment of younger officials because they quit, they can't handle it.”

And when coaches and fans act in an unruly manner, it takes a toll on the players who witness it.

“I mean, come on, these guys are not getting paid much to help us out,” said Giulino Panelli, who plays baseball for Legacy High School in Broomfield. “And we wouldn't be playing without them. Everybody makes mistakes with calls. It’s why they're there, to get better.”

That’s something Scott, who umpired in the majors from 1986 to 2017, tries to remind fans: Your kids are just starting out in this game and so are the umpires.

“You have little Johnny playing a game, he’s got some talent, but he’s learning the game of baseball. And they expect Division 1 college umpires to be there or something?” he said. “Umpires have to start out too.”

Major League Baseball holds a few free clinics at ballparks across the country every year for anyone interested in umpiring who might want to work games in the big leagues someday. Veteran umpires work the clinics to try to spot good candidates for umpire school, the pathway through which umpires make it to the pros. Participants not only receive situational training, but also advice on how to handle those moments where tempers are running high.

Former MLB umpire Rich Rieker, the league’s director of umpire development, says a good umpire will have sound judgment and good temperament.

“You know you're gonna get booed, it's part of the job,” he said. “Just know that they’re booing the umpire’s uniform, not the umpire, because nobody knows these people personally, really.”

It’s also important for the umpire to have fun while doing their job. It's a game, after all.

“If you start treating it like a game and having fun, your judgment, your reactions, are gonna be a lot better than if you think it’s a life or death situation,” said Ed Rapuano, who supervises umpires for Major League Baseball.

Grant Johnson, the umpire from Arkansas, refuses to let a few bad experiences with fans and parents take away from his dream of becoming a big league umpire.

“I’ve been playing since I was four years old,” he said. “People can say whatever they want to me, that's fine with me, it won’t change my love for the game.”

Eighteen-year-old Xai Menke of Greeley also umpires youth baseball games. He says it’s tough to do the job when “you have a parent yapping in your ear all the time.” But, like Johnson, his love for the game of baseball outweighs the negatives.

“I got diagnosed with Crohn's disease about three years ago and I haven't been able to play baseball that much,” he said. “And I felt like umpiring would keep me in the game and feel like I can still contribute to it.”

“Being on this field already, Coors Field, I've already smiled, I’ve secretly taken pictures already,” he said. “I guess a goal of mine would be to umpire a game here at Coors Field, just to get to the majors one day. I don’t care if it’s just for one game, just get to the majors at one point.”

So, maybe parents, coaches and fans can give umpires like Menke a break when they’re on the field, doing the best they can under challenging circumstances.

And maybe that anger over an umpire’s call is misguided anyway.

“I feel like it’s cruel, like maybe you're taking your team’s loss out on (the umpire) when really it's not his fault,” Panelli said. “Maybe your team just kind of sucks. I mean I'm a Giants fan. We’re not too good right now.”

More sports features

- Avalanche fans celebrate Stanley Cup championship run — and a job well done

- Love it or hate it, The Wave is wooing crowds all over the Colorado Rockies’ Coors Field

- Colorado’s Muslim community stands with Naz — an Avalanche player — after racist threats

- For a guy named Bones, a winding road to the NBA has him ready to show what he’s made of — and where he comes from

- Once Upstaged By A Taco Bell Quesarito, Now MVP, Denver Nuggets’ Nikola Jokic Has Come A Long Way