Imagine the following scenarios at a high school.

A student can’t find her dad, who is experiencing homelessness, so she can't get an appointment to go to the doctor. He has all her IDs.

A student experiencing homelessness can’t concentrate in class because of daily pain from a toothache.

A student's dad works in the oilfields, so she can’t get a ride to a doctor’s appointment.

A student who would rather die than disappoint or embarrass his parents by asking for mental health help.

These obstacles to medical, dental and mental health care are a daily occurrence in schools without their own health clinic, according to Lori Plantiko, a school counselor at Grand Junction High School.

“These are just a small sample of what obstacles affect grades, attendance, graduation rates and quality of life here at Grand Junction High School,” she told the Mesa Valley School District 51 school board at a meeting last week. She was speaking in support of a plan to build a school-based health center inside the new Grand Junction High School, expected to open next year.

But whether high school students should have easy access to health care has become a bitterly contested issue. Some city residents are pushing back. There’s an age divide. Nearly everyone who testified against the project at last week’s board meeting was older or retired, while high school students unanimously argued for it.

What are school-based health centers?

They are health care clinics located inside a school or on school grounds operated by a healthcare provider. Colorado has 70, eight of them on the Western Slope, according to Youth Healthcare Alliance, formerly the Colorado Association for School-Based Health Care. They offer students wellness checks, sports exams, strep tests, care for chronic conditions like diabetes, mental and sexual health care – and some offer dental screenings. They often serve underserved children and youth who have limited access to health care. More than 40 percent of Grand Junction High’s students are eligible for free and reduced-price lunch and a third are students of color.

Multiple national studies show higher grades and graduation rates for students who have access to school-based clinics, while absenteeism goes down. Other research has shown that school-based health clinics can reduce student hospitalizations, emergency department visits and overall health care costs.

“Parents can take less time off work, and students don’t have to take as much time from the class to be able to access health care because it’s right there at the school,” said Aubrey Hill, executive director of the Youth Healthcare Alliance. “The care is high quality, comprehensive, and it’s available regardless of insurance or ability to pay.”

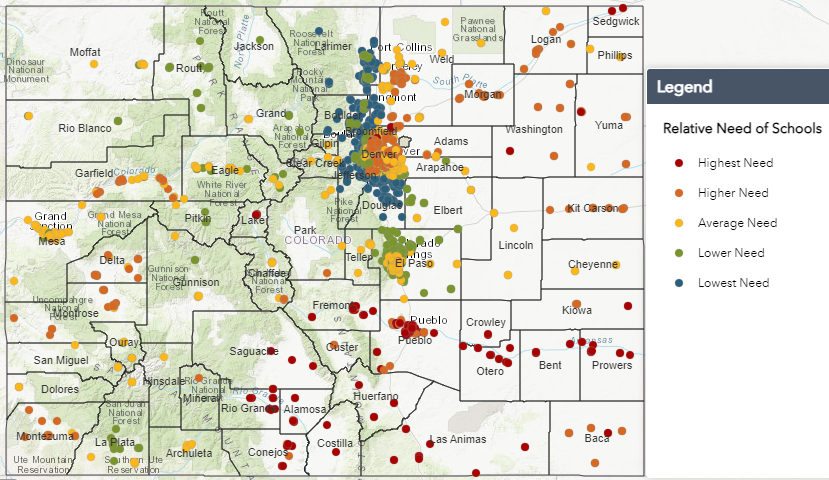

The Colorado Health Institute published a report in 2021 that identified 50 schools where students struggled with health issues. Three were in D51 schools. The report found schools with high numbers of students of color have significant health needs. It found schools in rural Colorado, particularly the San Luis Valley and southeast Colorado, had relatively limited access to school-based health centers. It found stark disparities in urban Colorado, with high need for clinics in Pueblo and Adams counties.

Central High School student Kenya Contreras recalls when she sunk into a bad depression last fall.

“I was unmotivated and at times all I did was cry in my bed for hours,” she told the school board at a recent meeting.

The champion wrestler said at her first match of the season she spent all her time sobbing. She decided to get help. Central High, another Grand Junction high school, has a clinic. She saw the free therapist at her school. He gave her strategies to help get through the season and through everyday life.

“From then on I’ve forever been grateful for the wellness center at Central,” she said. “It is simply a safe place for students to be treated as people for any need they have and to exclude other students from that experience, I believe, is simply unfair."

A parade of Central High students went to bat for their Grand Junction High peers at last week’s board meeting.

Karami Lyle told the board she knows they come from a different generation but said mental illness is widespread and severe in her generation. Lyle has anxiety-induced seizures. She’s gotten mental health care inside and outside of school. She said she’s lucky she has a supportive mom.

“But other kids have parents who disagree strongly with therapy, and those kids without clinics are unable to go because of needing a ride or payment method,” she said.

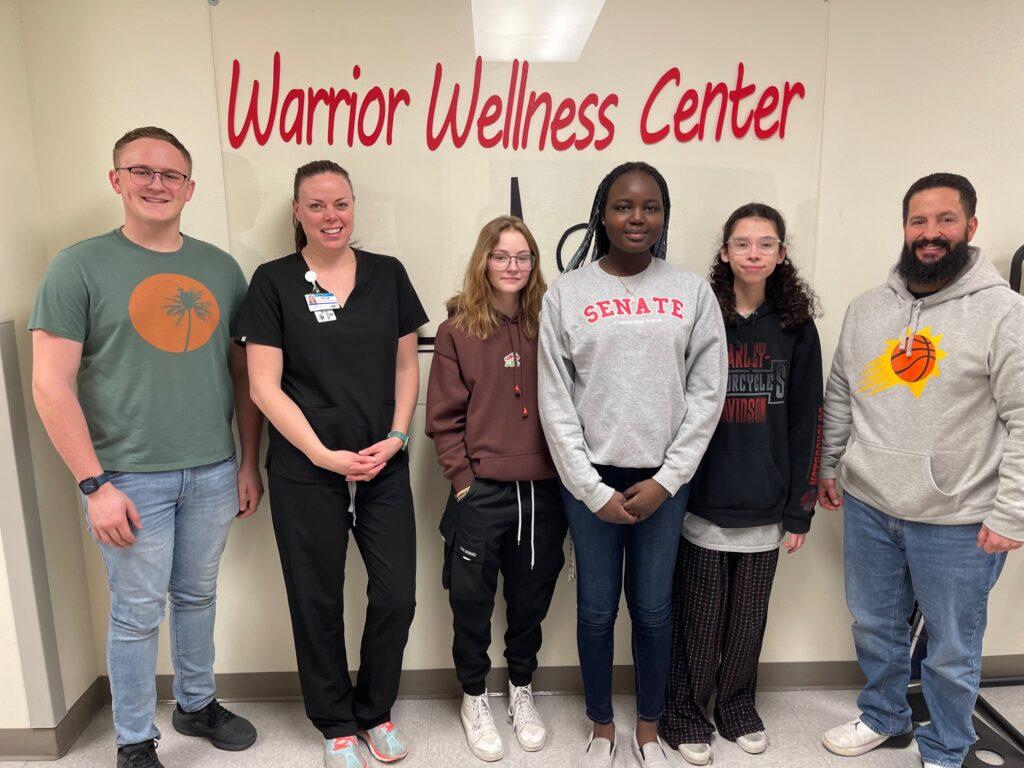

She and other youth noted that Central High has not had a suicide since the clinic came to the school in 2020, which she attributes to the help clinic staff Rosa Gardner and Steven Martinez have given youth.

“As someone who has lost multiple friends and my father by suicide and getting close myself, we need this wellness center. We need Steven. We need Rosa. And they need a Rosa. They need a Steven.”

The impetus for Central’s clinic began in 2017 when the community was rocked by opioid overdoses and several teen suicides. Since the clinic opened, the top five medical diagnoses have been sports physicals, acute cough, sore throat, headache and COVID-19 screenings. On the behavioral health side, it’s been depression, anxiety, stress from home, social anxiety and relationship problems, according to MarillacHealth.

‘There are citizens who feel betrayed by what is happening.’

On the other side of the debate were many older residents and some parents who oppose the project. Resident Jay Hosberg, who said he has not had children or grandchildren in the district, said when voters in 2021 overwhelmingly approved a bond to build a new high school it didn’t specify that a school-based health clinic would be part of it.

“There are citizens who feel betrayed by what is happening,” he said. “Bottom line, I now regret having voted for this project.”

Resident Anna Elliot said the ballot measure approved by voters should have specifically delineated a health care clinic.

“Do not ignore your taxpayers or invite legal challenges,” she said. “Future funding requests will be difficult to secure if you do.”

Some parents worry about being kept in the loop about their children’s health care, and some worried that students can access contraceptives in the clinic.

Retired nurse Connie McDowell called the proposed clinic an injustice to the doctor-patient relationship.

“We should not diminish or bypass the pediatrician or the family doctor visits when seeking care for physical, emotional or mental health concerns,” she said. “It's vital to preserve the child, patient, doctor relationships here in our community.”

Cindy Ficklan has a son at Grand Junction High.

“A school district itself cannot be all things to all people, and the district does not need to insert itself in between parents and students,” she said.

But many residents weren’t aware of rules surrounding school-based health clinics and Colorado law.

Parental consent is needed for most medical services at a clinic, including vaccinations. There are exceptions. Colorado law allows minors access to reproductive services like STI testing and treatment and substance use counseling without parental consent at any clinic or pediatrician's office in the state. Colorado law allows minors 12 and over to access mental health services on their own.

For the period of August to December 2022, the vast majority of medical visits to Central High’s clinic involved parental consent. Mental health visits were evenly split between minor and parental consent.

Just a tiny fraction of thousands of clinic visits over the past two and a half years at Central were for contraceptive services.

Rosa Gardner, a physician assistant who provides care to students at the Central High clinic, said the staff encourages students to involve parents as much as possible.

“We are not in the business of creating divides between parents and children,” she said.

Most of her work consists of sprained ankles, sports physicals, concussion evaluations and strep tests. But other visits are more urgent. The clinic helped a student who was missing school because of chronic stomach pain get a formal diagnosis. A surgery to correct the problem was scheduled. In the meantime, the student is back in class because they learned techniques to manage triggers for their pain.

“Imagine how much easier it is to learn when you're not in constant pain,” Gardner said.

A student stopped taking their medication because their psychiatrist moved away. Their hallucinations came back at school. The clinic connected the student to a new outside psychiatrist and the student resumed taking their medicine.

In all cases, Gardner said parents were involved and grateful for the help their child received. That’s true especially for low-income youth.

“They come to us at the clinic because they can’t go anywhere else,” she said.

The fact of the matter is, even for parents who have close relationships with their teen children, youth don’t tell their parents everything.

That’s what Dr. Laura Campbell, a family practice physician who will have a freshman at Grand Junction High School next year, told the school board.

“Having another trusted adult in those children’s lives is critical,” said Campbell. “I would want to make sure that there is another trusted adult in the life of my kids if I can’t provide all they need.”

That’s all the more important when teen mental health is at crisis levels. A recent CDC report finds unprecedented levels of hopelessness and suicidal thoughts among U.S. high school students. Nearly three in five teen girls said they felt “persistently sad or hopeless."

“We need this medical clinic. We need help,” said Grand Junction High teacher Justin Whitehead.

Board chair Andrea Haitz said some community members asked if the clinic could be next to the school but said MeriallacHealth said that plan wouldn’t work. The health care provider would fund the clinic, operating in the school rent-free, with the district paying a one-time fee of $247,000.

“It’s unfortunate because we’re trying to figure out a way to have a ‘happy medium’ on both sets of concerns on this issue,” Haitz said.

Board member Kari Sholtes said another factor is student safety. Modern school buildings limit student access to and from the building.

“It’s not just about what Marillac can accomplish in a school-based health center but also: how do we keep our kids safe? That also does play a large role in where that facility can be located.”

The board is expected to vote on whether there will be a clinic at Grand Junction High School next Tuesday.