Colorado’s history can often be headline news. That includes things like the proposed renaming of Mt. Evans or the removal of a statue of a Civil War soldier. It prompted a listener to ask CPR’s Colorado Wonders a question: What Native American tribes lived in the area now known as Denver?

It came to CPR News from Darlene Graham, a retired Denver Public Schools teacher. She remembers learning about the Ute tribe but not much more.

“I think it's fifth grade where they study Native Americans in this area. It's just a fascinating subject,” she said. “I think it's sometimes kind of forgotten.”

Standing in downtown Denver, Ernest House Jr. would agree.

“We're sitting here on the banks of the confluence in downtown Denver and as I'm looking around, I saw people that were fishing, that were meditating, that were just walking their dogs,” said House, a member of the Ute Mountain Ute tribe from southwestern Colorado and a former executive director of the Colorado Commission of Indian Affairs.

“I go back in time and think about how our tribal nations had also utilized this area. Water's so important,” he said.

Water was the lifeblood, helping sustain people in this region for 12,000 years or more.

The Utes and other tribes lived on the mountain side of the South Platte. And, House said, on the other side lived “the Plains tribes, those tribes that were moving with buffalo, they were utilizing horses, large horse tribes like the Comanche, like the Sioux Nations, Cheyenne, Arapahoe, so on.”

They traveled and traded around this region and beyond.

“There was an I-25 corridor long before any type of concrete was laid down that these tribes, our tribal nations have always also been here but often are overlooked or the story's never told,” House said.

At least 48 other nations occupied this land in the last 500 years. Then, waves of Euro-American explorers, trappers, traders and eventually settlers pushed in, often violently.

Tribes, House says, were “forcibly removed by treaty or by gunpoint from what we call the state of Colorado over the last 150 to 200 years.”

Complicated, violent history

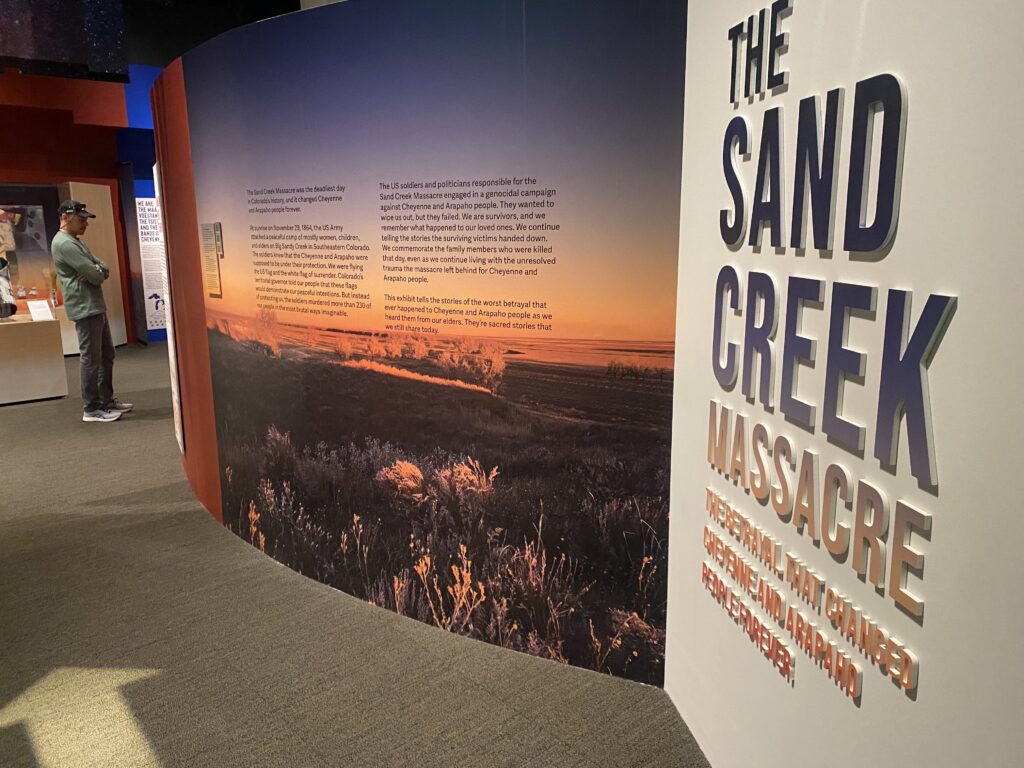

History Colorado, the museum in downtown Denver, has been grappling with this complicated, bloody story. Last fall, it opened a new exhibit on the Sand Creek Massacre, the deadliest day in Colorado history, which was developed in consultations with tribes.

“You can't understand the creation of Colorado without understanding both the Sand Creek Massacre and the Gold Rush. They're all connected,” said Sam Bock, publications director and lead exhibit developer for History Colorado.

Growing settlement on the land took off with the Gold Rush. Disease took the lives of many in tribal communities. Then in the 1860s, the U.S. used Colorado gold to help pay for the Civil War.

“The people coming to mine that gold were hostile to the Indigenous peoples who had been living here for hundreds of years,” said Bock.

To protect Denver and the mines, the U.S. sent troops. In 1864, the U.S. Army attacked a camp of mostly women, children, and elders on Big Sandy Creek in southeastern Colorado, as the exhibit documents. The soldiers murdered more than 230 peaceful Cheyenne and Arapahoe people.

“It's really one of the most important moments in Colorado history,” said Bock.

That moment came after a string of treaties were broken by the government, with John Evans, the second governor of the Colorado Territory from 1862-65, playing a central role.

“We were here defending our land,” said Richard Williams, executive director of a nonprofit called People of the Sacred Land, who is Oglala Lakota and Cheyenne. “There was not a single person who was in Colorado at that time that was here legally.”

Sand Creek also set the stage for more death and devastation.

“These people were pushed very far away from their homeland,” Bock said. “They were pushed into residential boarding schools where their children against their will were taken and, and oftentimes, sadly had their language and culture literally beaten from them.”

The Sand Creek Massacre is a key moment in the history of the entire hemisphere, Williams said.

“Our, my, ancestors were living in their homeland, and they were surviving in a very comfortable manner. And they were annihilated,” said Williams, an educator and former CEO of the American Indian College Fund. “Sand Creek, and the before and after of Sand Creek, from about 1861 to about 1869, is the worst case of genocide in the Americas.”

Reconciling the past with the present

Momentum is building to revisit the past with an eye toward restoration and reconciliation.

In February, hundreds gathered at the Denver Indian Center, an urban cultural gathering center for the American Indian and Alaska Native community, which makes up roughly 2 percent of Colorado’s population, according to the U.S. Census. They were there for the kickoff of an event aimed at sharing the history of Denver’s American Indian and Indigenous Peoples communities.

“I think that we need to be able to tell our own story,” said Williams, who gave an invocation.

Community members, surrounded by the flags of Native American nations that decorate the walls of the center, joined in a traditional round dance along with Seven Falls Indian Dancers.

Denver’s Landmark Preservation team and Office of Storytelling are developing a written study and a documentary. Community members are telling their stories.

The state too is working to bolster the historic record, including about the dozens of tribes with ties to the land here.

"History Colorado and the Colorado Commission of Indian Affairs held tribal consultations to make a list of these 48 Tribes that have ties to what is now known as the state of Colorado,” said spokesperson Melissa Dworkin in an email. That includes the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and Southern Ute Indian Tribe which have jurisdictions in Colorado.

An exhibit at History Colorado called Written on the Land documents the story of the Utes, Colorado’s longest continuous residents, told in their own voices.

Currently, there are over 200 Tribal Nations represented in American Indian/Alaska Native communities in the Denver metro area, according to Dworkin.

Williams said history also requires a hard, often painful look at how Colorado was formed.

“You only need to ask yourself one question. Why are there no Indian reservations on the front range or in eastern plains of Colorado? And it's a sad story.”

Williams hopes in better remembering, chronicling and understanding its history the people living in the land now known as Colorado can seek truth and chart a better future.

For him, the effort is long overdue.

“One hundred and fifty years,” Williams said.

So who's who?

Courtesy of History Colorado.

Many tribes have called this place home. At least 48 tribes have lived at times throughout the land we now call Colorado.

The Ancestral Puebloan People were farmers who lived in the southwest part of Colorado for thousands of years. They built homes, villages, and cliff dwellings. (In the recent past, they were incorrectly called “Anasazi”.) Their modern descendants are these federally-recognized nations:

- The Hopi Tribe, Arizona

- Kewa Pueblo (formerly the Pueblo of Santo Domingo), New Mexico

- Ohkay Owingeh (Pueblo of San Juan), New Mexico

- Pueblo of Acoma, New Mexico

- Pueblo de Cochiti, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Isleta, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Jemez, New Mexico)

- Pueblo of Laguna, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Nambe, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Picuris, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Pojoaque, New Mexico

- Pueblo of San Felipe, New Mexico

- Pueblo of San Ildefonso, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Sandia, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Santa Ana, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Santa Clara, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Taos, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Tesuque, New Mexico

- Pueblo of Zia, New Mexico

- Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, Texas

- Zuni Tribe of the Zuni Reservation, New Mexico

The Nuuciu, today known as the Ute, lived for generations in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico. They moved with the seasons to hunt and gather everything they needed and traded for horses. Today, the Utes are three tribes:

- Southern Ute Indian Tribe, Colorado

- Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, Colorado and Utah

- Ute Indian Tribe of the Uintah & Ouray Reservation, Utah

Southern Ute and Ute Mountain are the only two Indian Reservations in Colorado. Tribes of the Great Basin lived in what is now western Colorado, and developed ways to live in a challenging desert environment. Their modern descendants are part of these sovereign tribes:

- Navajo Nation, Arizona and New Mexico

- Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah

- San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe, Arizona

Many different tribes lived and moved through the Great Plains of eastern Colorado. Their lifeways centered on hunting bison, following a seasonal round, and trading for horses and other goods. Cheyenne and Arapaho people are today part of these tribal nations:

- Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma

- Northern Arapaho Tribe, Wind River, Wyoming

- Northern Cheyenne Tribe, Montana

Many tribes were closely connected to the Southeastern plains of Colorado, their descendants are part of these tribal nations:

- Apache Tribe of Oklahoma

- Fort Sill Apache Tribe, Oklahoma

- Jicarilla Apache Nation, New Mexico

- Mescalero Apache Tribe, New Mexico

- Comanche Nation, Oklahoma

- Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma

- Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma

- Osage Nation, Oklahoma

- Wichita & Affiliated Tribes, Oklahoma

Many tribes were closely connected to the Northeastern plains of Colorado, their descendants are part of these tribal nations:

- Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, South Dakota

- Crow Creek Sioux Tribe, South Dakota

- Oglala Sioux Tribe, South Dakota

- Rosebud Sioux Tribe, South Dakota

- Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, North Dakota

- Three Affiliated Tribes Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation, North Dakota

- Crow Tribe, Montana

- Eastern Shoshone Tribe, Wind River Reservation, Wyoming

- Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, Idaho

Funding for public media is at stake. Stand up and support what you value today.