Jason Van Tatenhove spent years as the media director for the Oath Keepers, a far-right militia group. He broke with the organization long before their involvement in the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol building and has since become a public face warning of the dangers of extremism.

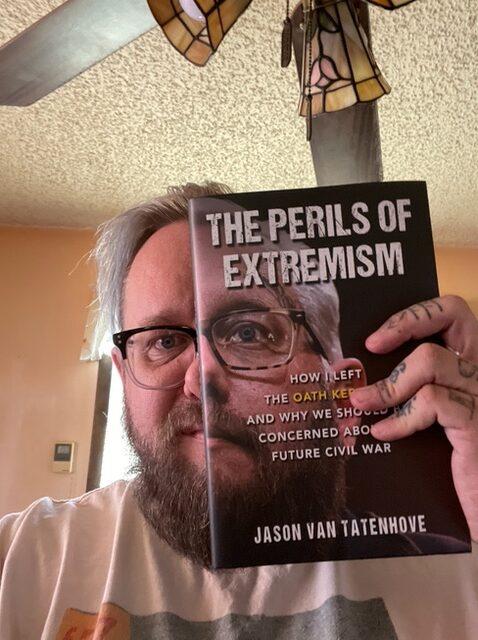

Van Tatenhove’s new book, “The Perils Of Extremism: How I Left the Oath Keepers and Why We Should Be Concerned About a Future Civil War” details how the organization evolved through the years.

He spoke with Colorado Matters host Ryan Warner.

Interview Transcript

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

RYAN WARNER: People may recognize your name because you testified before the January 6 Commission on the inner workings of the Oath Keepers and why you left. I want to start with some assumptions about your story. It would be really easy to see your book and your testimony before congress and think, this is a militia member who had abandoned his dreams of overthrowing the government and now seeks to repent. But that’s not at all the story of your time with the Oath Keepers, is it?

JASON VAN TATENHOVE: No, not really. I really felt it was important for my own personal journey to get the story out there, to write the book so that I could tell the story in my own words. And, it really is a slice of my family’s life during that period of time.

I kind of went into this misadventure with the notion to write a book. I had read a whole lot of Hunter S. Thompson. I had been moving through his omnibus. I had been very struck by his Hell’s Angels novel and thought that this might be an opportunity for me to write a similar novel that pertains to our generation.

RW: And so you call this a “misadventure.” So you began it as an adventure and it became a misadventure?

JVT: You know, it really kind of all started, when I had moved from the Fort Collins area to Butte, Montana about a year before Bundy Ranch had kicked off. And Bundy Ranch is kind of my first mile marker when it comes to this adventure.

RW: Let me just say that was the 2014 standoff in Nevada over cattle grazing permit fees, right?

JVT: Yes. It was 2014 in Bunkerville. That really is what kicked everything off because that's when we saw Cliven Bundy putting out messaging calling up all good patriots and good Americans to go join him in the desert of Nevada and square off against the federal government. I kind of started hearing this, I think it was originally on Fox News, but really where the big coverage was coming from was Alex Jones' Infowars. And I just remember thinking, something is happening. This is something big. Something in my gut was saying, ‘I want to get out there.’ And, you know, as a storyteller, as a writer, I feel the only way to truly figure out what's happening is you gotta go be there and figure out who the players are, see what the dynamics are and just see it with your own eyes and experience it. And, you know, I'm very influenced by participatory journalism. I think that it's just something that spoke to me in the stuff I was reading.

RW: But at a certain point you kind of become the media person for the Oath Keepers?

JVT: I do. And I don't want to gloss that over. I feel it's very important that I acknowledge that I began becoming radicalized myself over time. And, in some ways, I didn't even see it myself until we kind of hit some thresholds. You know, the lines I just couldn't cross. But I want to take responsibility for that. And the work I've been doing since then, I've really been trying to recognize the influence that I had and to try to make it right. In my own mind.

RW: You write in the book:

“I think that a lot of the people who are involved in the patriot movement are a little lost, looking for answers. And when the real world doesn't make much sense, they turn more and more to conspiracies.”

Connect that with Stewart Rhodes. Does he prey on that?

JVT: He does. He certainly uses it. And that's part of the formula. My original title for the book was not “The Perils of Extremism.” That was a decision made by the publisher — along with putting face on the cover, I would've never done that. But the original title was “The Propagandist,” because really what we were doing was creating propaganda.

I'll be the first to admit that I am a conspiracy-theory junkie. There's just something about it. From my early adulthood growing up in Fort Collins, I spent a lot of time around the CSU campus. I would ingest a lot of alternative documentaries that would come through the student center. Some of the ones that had a very profound impact were the documentaries revolving around the Waco incident and then Ruby Ridge.

And, part of the messaging that was being put out for Bundy Ranch was that there were sniper teams in the hills around the family ranch and that it was just a matter of time until we saw another Waco or Ruby Ridge happening there. You know, obviously, that was the messaging that was being put out.

But, as far as Stewart using that type of conspiracy theory and propaganda, that's a part of the formula. If you go back and look at the initial kind of mission statement of the Oath Keepers, it revolved around 10 orders that we would not obey. And, of course, the namesake of the Oath Keepers is the oath that law enforcement and military and politicians take swearing to uphold and protect the constitution from enemies foreign and domestic.

It really revolved around what was called the Jade Helm Conspiracy, which was a conspiracy during the Obama era that kind of took hold. It revolved around the notion that the UN was actively doing trainings with the U.S. Army and National Guard to round up right-wing conservatives, gun owners, and put them into some sort of concentration camp in decommissioned big box stores like Walmart. Really, we see this cyclical pattern where, you know, whatever the hot conspiracy theory of the day is, that's where they're going to insert themselves into that messaging and kind of weave themselves into these stories.

RW: That strikes me as opportunism, Jason.

JVT: Absolutely. That's exactly what it is. It's a good grift, you know, and these are formulas that are kind of laid out originally by a writer. He wrote the book "Propaganda," and it was Edward Bernays, who actually was a nephew of Sigmund Freud. It's a manual, basically, of how to create propaganda. You look for that strong emotional reaction — that low-hanging fruit is really anger and outrage. You find those really hot-button stories that people are having a strong emotional reaction to and then you rewrite those stories, inserting, in this case, the Oath Keepers’ name into them. That’s kind of like a commercial, where you get that strong emotional reaction and you associate a brand logo with it. It seems to have almost a short-circuiting effect on critical thinking skills.

RW: In some ways you didn't quite fit into this group. You write that you dressed differently, wearing a lot of punk rock shirts, acted differently. You say you identify as queer. Were you welcomed by this crowd?

JVT: Actually, I was. And you know, I come from a very left household. My grandfather was one of the abstract expressionists in New York City back in the ‘50s. I was kind of raised by the remnants of the beatniks of the New York City scene where it wasn't uncommon to rub elbows with militants. Originally, I think I kind of got radicalized because I do have a healthy distrust of the government. And, I think there's plenty of reason to distrust the government. There are many historical pieces of evidence that lead me to that. Now, obviously my views have evolved quite a bit.

And I was never one to bring a firearm to any of these things. I was bringing a microphone and a keyboard and a camera. But, I certainly became radicalized in that. And part of that was the media I was ingesting as my job.

I'll be honest with you, things weren't going so great for me, either. I was a bit lost. I had sold a successful tattoo shop I had in the Fort Collins area. I moved my family out there and with plans of using those funds to start another tattoo shop in the Butte area. But the economic realities and the cultural realities; it just wasn't the same place as Northern Colorado.

RW: You know, there's been this storyline that undergirds extremism. I think it has undergirded Trumpism as well, which is that economic unease is what drives these folks. There's also a lot of pushback against that, that it's racism and misogyny.

JVT: I think it all starts with poverty. And that's from my traveling around and in my own story. You gotta understand, specifically with the Oath keepers, we saw a creep toward the hard right. Before Bundy Ranch really happened and kicked off, it almost seemed more like an anarchist book club. There wasn't direct action. They weren't doing, you know, armed standoffs where they were pointing guns across at federal law enforcement agents. But once Bundy Ranch happened, I remember overhearing conversations that they had raised close to 30 to $40,000 in a week. I think that really changed Stewart's direction — that he saw an opportunity there and he also saw just how much camera attention nationally and internationally it garnered, which led to greater membership. It also led to greater donations. I think really, in Stewart's mind, it steered him toward standoff after standoff after standoff. In pretty quick succession we went from Bundy Ranch and then up to Josephine County, Oregon for what was called the Sugar Pine Mine standoff.

RW: It's fascinating because it does strike me as something of a traveling show, you know, like the opportunism I think that you reflect on.

JVT: I'll be honest with you, I had never traveled much previous to this. Part of the draw was I got to go all over the country and meet all kinds of people. I was flying to work some days on an old, Vietnam-era Huey that was piloted by a Vietnam-era pilot. There was kind of an adventure aspect to it.

RW: Is it a lot of guys who just kind of want to play GI Joe?

JVT: Yes and no. It certainly is a part of it. I think one of the reasons, you know, Stewart focused on the veteran community is because they're looking for that camaraderie again. And, let's face it, our veterans have not been treated well when they return home, historically. When someone like Stewart comes in and says, “We’re going to have this community, we're going to go out on missions again, and these missions are important to the future of our country” that resounds with a lot of people. Especially if things aren't going as they had planned, necessarily.

And this helps to, to foster that to an extent. Now, what I will say is, the membership that I had experience with largely did not have all that much combat experience. The guys that did have real combat experience are fairly squared away. They have a pretty short fuse when it comes to BS. They would come in and pretty quickly see this as a cult of personality.

But, there were also these cottage industries that kind of sprung up around the militia movement up there in the Pacific Northwest, specifically. So you had actual war fighters who were providing training, actual real military training to the more armchair warrior types.

RW: What do you think Stewart Rhodes saw in Donald Trump?

JVT: I think he saw opportunity, and that was not always the case at first. He was not very excited about Trump, actually. The day of the election, he wasn't even gonna go vote. I was actually the one that encouraged him, saying, “hey, you're the leader of this veteran political organization as you term it, and you need to get out there and vote.”

At first that was the case but over time he saw it as an opportunity. I think his dreams for the Oath Keepers was to create this kind of paramilitary force that, given the right political circumstances, could find authenticity and legitimacy. He pretty quickly saw a route to that with the Trump administration. That's evidenced by the security that was provided on January 5th and the January 6th events.

RW: We're recording this conversation just after a first in this country: the first time a former U.S. president has been indicted. The case involving former President Trump is separate from the January 6th siege. But, I do wonder how you see the indictment playing out in your former circles.

JVT: Well, you know, it's kind of a “wait and see” moment at this point in time. Part of what I talk about in the book is this kind of fringe element that kind of surrounds the more organized national groups. At one point, if actual Nazis and racists were to show up, they would kick them out. That's changing. Now, we're seeing this evolution where we have this creep to the hard right, where racism is becoming much more blatant and much more accepted. Christian nationalist views are being pushed out in the open. So, we're just coming to a more extreme place, a more extreme reality. It was very concerning for me to see Trump have his first official rally in Waco, Texas, because I think now he's speaking directly to those fringe groups that in my opinion are more apt to perpetrate violent actions.

RW: You eventually spoke in front of Congress about your time with the Oath Keepers, which I'll reiterate ended years before the January 6th siege. You explained the moment you left the organization about homophobia, anti-Semitism, racism, that in the end, you couldn't abide.

JVT: The straw that broke the camel's back really came when I walked into a grocery store. And we were living in the very remote town of Eureka, Montana. There was a group of core members of the group of the Oath Keepers and some associates, and they were having a conversation at that public area where they were talking about how the Holocaust was not real. And that was for me, something I just could not abide. And, you know, we were not wealthy people at all. We were barely surviving and it didn't matter. I went home to my wife and my kids and I told them that I've gotta walk away at this point. I don't know how we're gonna survive or where we're gonna go or what we're gonna do, but I just can no longer continue and put in my resignation.

RW: Say more about that instance. Why was that the straw that broke the camel's back for you?

JVT: It's easy to try to pigeonhole members of a community as being racist. And that's not always the case. As I had mentioned earlier, I could get behind kind of being somewhat anti-government or skeptical of the government, and that certainly became more extreme over time. But I've never been a racist person. I was not raised that way. I mean, I have letters of correspondence between Martin Luther King and my grandmother. I come from a blended family. My cousin and aunt are Jewish and we would have blended holidays growing up as a kid. My granddaughter these days is Latina. So for me, I just, that was not something that in my core being I could deal with.

RW: What did you do as a propagandist that you carry some shame around today?

JVT: Since January 6th and my testimony, I began doing work. I'm now a consultant with Georgetown Law’s ICAP, the Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection. I have another major university that I'll be working with as well. I do talks all over the country. I'm working with some of the people that are really asking some of these big questions: How do we avoid this in the future and try to get to a better place? So, you know, I realized that I played a part in this and it may have just been words that I was using, but I think those words actually can be more effective and more powerful than any bullets because, you know, ideas are something that take root and they grow.

And, you know, I certainly played a part in planting those seeds. So now I'm trying to replant a new crop of seeds because I really think a lot about the world my daughters are gonna inherit. January 6th, watching that in high definition, in real time on my couch with my daughters really was a gut punch for me. It made me feel physically ill because that was really the realization that I had some influence on the through line from Bundy Ranch to what we saw on January 6th, where there was an attempt to take apart our democracy. It was a failed coup in my opinion and I have to make right on that. I have to try to do better.

I'm really good at screwing up. I'm really good at it. I think a lot of us are. Part of that life experience is learning from those and trying to do better and trying to create a better future because no one's coming to save us. No one's coming to fix this for us. We have some really big issues that we're grappling with, whether that be climate change and political divide and violent extremism. The wheels seem to be falling off. You know, America's not perfect, but it's the best we got and we've made some real, real progress in the last 60 years or so. Right now, I think we're in danger of losing that progress that my grandparents contributed to, your grandparents contributed to. And we've gotta figure out how to keep that from happening and how to move forward again and get to a better place than we were. So that's on us. And, and you know, that's on me.