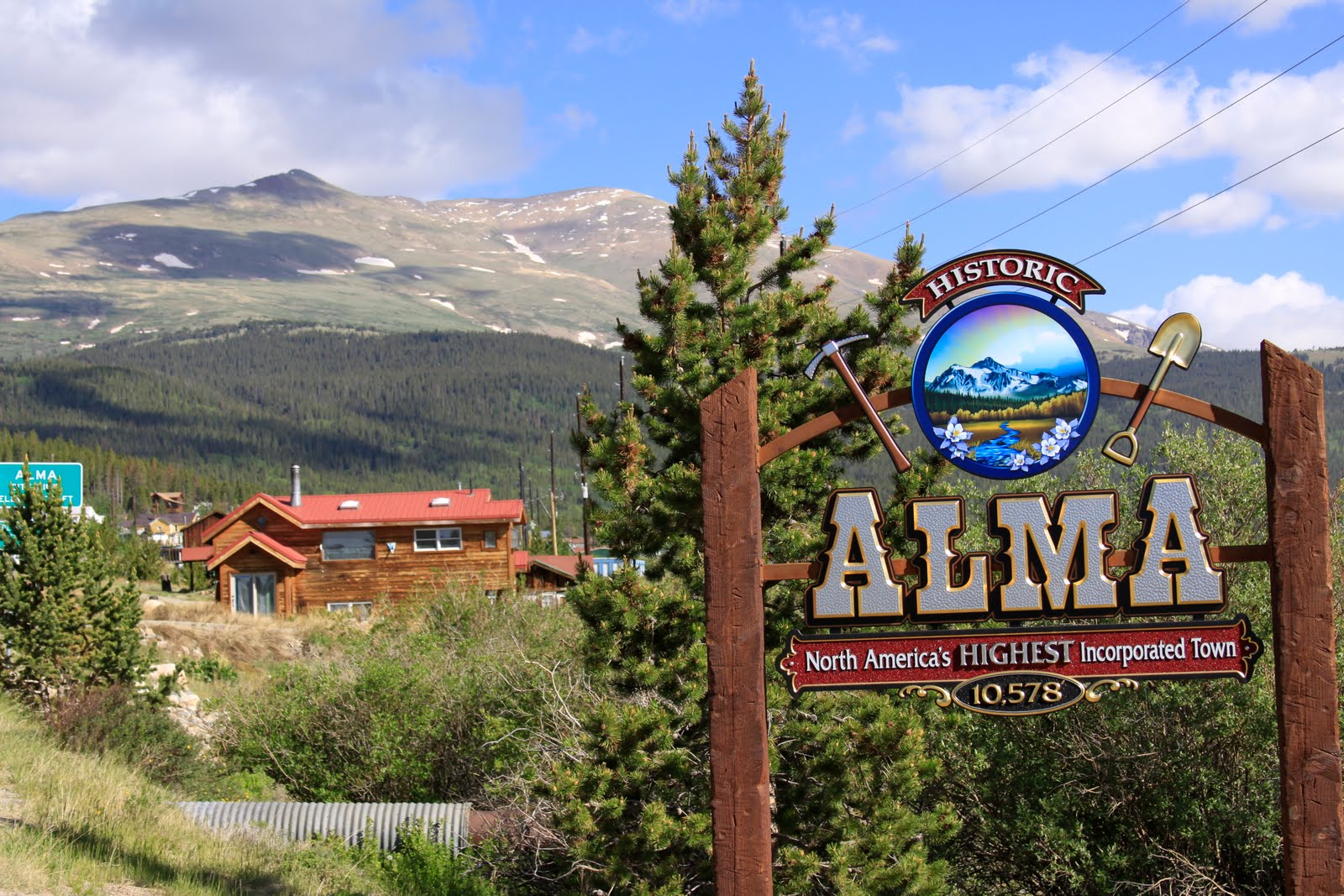

The town of Alma, about 90 miles southwest of Denver, held its first town meeting in the 1870s. Measuring a mile long, it now has a population of between 250 and 300. And it has a feature no place else in the US can boast: the mining community is the highest incorporated town or city in all of North America, at a towering 10,578 feet.

Twelve years ago, the town found a way to show off its altitude – by purchasing signs to demarcate the town and featuring that elevation number on the bottom.

Grounded with two wooden staffs, the sign has a curved wooden arch upon which an image is mounted. It shows the mountains with a rainbow in the background and flowers in the foreground. On either side are mining tools – a pick and a shovel. In 2012, the town installed two such signs about a mile apart – at the start and end of the town.

“The new ones have our new logo on them, which is gorgeous,” said town Administrator Gary Goettelman.

“I think they’re some of the most beautiful town signs I’ve seen around. It has a river and some columbines, and it’s kind of a whole mining-based theme, which is our entire town,” he said. “We just made it nice and big and there’s mining artifacts and everything ... they truly do have real gold and silver in the paint within the sign as well.”

Alma’s wooden arched signs with mining tools on top – noting just the town’s name and elevation – are larger, pricier and fancier versions of what Colorado usually provides towns by way of identification signage.

That’s what some research turned up while responding to a CPR audience member’s query, which said: “I am curious to hear if there is an interesting backstory that explains how Colorado towns decided to publish the elevation on their signs.”

In Alma, it was for the bragging rights: those coming through town tend to take note.

“People stop and take pictures by the signs constantly,” said Goettelman, who was mayor when the signs were made.

But the Centennial State doesn’t generally just go around creating the detailed, stylized signs the town of Alma made – which city funds paid for – but they do take care of the cost of basic signs that feature just the elevation on them. And it turns out the backstory of why and when this began is in fact interesting.

“OK, so the way it works is signs generally just have the elevation,” said Bob Wilson, spokesperson for the Colorado Department of Transportation. “Generally they don’t have the population. . . . the reason for that is because since the population can change and usually does change in most locations, the cost of replacing signs would be prohibitive. . . .whereas elevation – that doesn’t change.”

Another reason: there are rules. Colorado’s Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, which includes signs, considers it standard to provide “only as much information to the road user as necessary to promote the safe and efficient operation of streets and highways,” Wilson pointed out in an email, adding a bit of text from the manual:

“Sign clutter can result from the overuse of MUTCD-compliant signs and/or signs that display information unrelated to traffic operation, navigation, or transportation information. Examples of such signs would include, but are not limited to, those displaying the birthplace or home of a noted person, local sports team accomplishments, population information, and self-described qualities of a community such as ‘friendly’ or ‘open for business.’”

That led to the question, isn’t the elevation of a town or city – of which Colorado has 273 – considered information unrelated to traffic operation, navigation, or transportation information?

On the contrary, it is information related to navigation. That’s because people are advised to navigate their trip into or through the state with Colorado’s atypically high elevation in mind, because as one goes higher in elevation, the amount of available oxygen decreases, which can cause altitude illness.

Wilson provided a link to the CDC’s guidelines for traveling in high altitudes as an explanation for the need for the information on signs. The guideline sheet begins with the warning: “If you plan to travel to an elevation higher than 8,000 feet above sea level . . . you may be at risk for altitude illness, which is caused by low oxygen levels in the air.”

The guidelines describe three levels of altitude sickness: The mildest form is called acute mountain sickness; its symptoms include headaches, tiredness, lack of appetite, nausea and vomiting. The second-most serious form is called high-altitude cerebral edema, which can cause confusion and loss of coordination as well as drowsiness. The most serious variety is called high-altitude pulmonary edema, which can be life-threatening; its symptoms include shortness of breath, weakness, and cough, according to the guidelines.

Some of its tips include a gradual ascent, no drinking alcohol or doing heavy exercise for the first two days after arrival and sleeping at elevations lower than the elevation of the day’s activities.

San Lee, who has served for 21 years as Colorado’s traffic engineer, sees the value in the elevation of signs, which he calls “super-important strong communication tools that we use across the state.”

“Elevation is associated with certain medical conditions through the CDC,” he said, “so we want to make sure that we’re giving information that’s critical for the public when they’re traveling.”

He said he had a friend visit from Florida who was confronted with altitude sickness. “She has to monitor those elevations to make sure she doesn’t exceed certain elevations ... or she uses supplemental oxygen when she hits certain elevations,” he said.

He said the signs, made of aluminum with durable retro-reflective sheeting, cost about $2,500 each and usually last about 10 years before they are damaged by weather or a collision with a vehicle. The cost includes materials, labor and installation.

When asked what would happen if a town requested something other than the elevation on its state-supplied sign, he said CDOT would accommodate the request – as a one-time thing.

Lee said in an email that the only known request came from Grand Junction, which asked for both elevation and population on its sign; the state complied. He added that Colorado towns that don’t have a state road or highway running through them are responsible for taking care of their own signs, so it’s possible other towns came up with their own self-funded signage, like Alma did, and the state wouldn’t necessarily know about it.

In creating its signs in 2012, Alma didn’t ask for state funds – they used their own dollars to order their unique signs – and they weren't cheap. “I want to say that they were in the realm of five, six grand apiece,” said Goettelman.

“It was a pretty significant investment for the town and coming up with the artwork and changing that logo and everything else ... but I think it branded the town very nicely, and we certainly will never have to go through and do that again,” he said.

The backstory on elevation signs began nearly three-quarters of a century ago. It seems it was the media that urged the state to consider having signs featuring elevation. A newspaper called the Craig Empire Courier, in a Sept. 7, 1949 story, suggested making signs more interesting by putting some information on them besides the name of the town.

“... it is plain that the highway department could easily enhance the interest tourists would have in our state after we asked ‘em to come and see us,” the story states.

“One of the first things any visitor, especially one from them [sic] coast or plain states asks is what is the elevation. That is usually followed by an inquiry as to what is the population of the town or city. This information could be easily added to the sign when the highway department has at each city limit,” the article continues.

“Then, to go just a step further, a line could be added to the signs in which the principal industries of the community would be enumerated … possibly only three words allowed in this line and the information in this line to be furnished by some reliable organization in the city.”

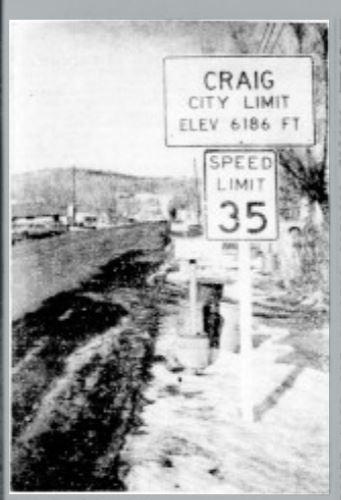

The publication was helpful enough to offer an example of what the sign would look like for Craig, in Moffat County. Its population is now about 9,000, but back then, there were about 4,200 people living there.

The Craig Empire Courier created and published a mock-up of a sign that would work for Craig, writing above it: “If we should do this, a city limits sign would look something like this.” Below that is a white sign with black letters. In the top left corner, the elevation of 6,200 would be noted; at the top right would be the population, then 4,231. In the center would be the name of the town or city, above the words “City Limit,” and running right to left along the bottom would be the town’s main industries: for Craig, that would be Sheep, Cattle and Oil, per the prototype.

It appears that the state took the suggestion seriously – at least the first part – about 15 years later. The picture on the front page of the January 31, 1964 edition of a newspaper called Yampa Valley Flashes, is of a street sign that reads “Craig City Limit Elevation 6,186.” It appears on a post above a sign with a speed limit of 35 miles per hour.

If the elevation signage was truly because of the newspaper’s suggestion, the state used some discretion: the transportation department went along with the paper’s tip about putting the elevation on signs, but said no thank you to the suggestion of also adding the town’s population and primary industries – that would go against the regulations in the manual from which Wilson had quoted.

Whether or not the state’s impetus to put elevation on signs was influenced by the newspaper’s suggestion isn’t clear, but it is clear to San Lee that the information serves a purpose: “Standards and specs and signs were one of my favorite parts of my job because you can help improve safety through signs, and help people get where they want to go,” he said. “When we have recreational activities, when we have job interviews, they help us get where we’re going.”

In Alma, town administrator Goettelman thinks the information on his town’s signs is sufficient without the key industries or the population – which jumped from 297 to 325 in recent years, he said, citing 2020 census data.

That, he said, is a relatively unimportant factor to point out, when compared to the elevation factor.

“No, I just think they need to know how high we are. Nobody else lives at 10,578 feet in North America, do they? We call it leading by example from above, is what we do up here.”

CPR News Transportation reporter Nathaniel Minor contributed to the research for this report.