Inside an airy, modern house near South Denver, there are large windows, hardwood floors and a bathroom the size of a bedroom. When it opens in January, as many as 14 women will be able to spend eight weeks there, getting healthy with vitamin infusions, neurofeedback and even someone to decorate the place to make it as soothing as it can be.

“We have a trauma-informed interior designer that's coming in to cultivate each of these spaces,” said Britney Higgs, the founder. “That's important for us too, that you walk in and it is a space that's curated for healing.”

It’s not a spa or a retreat, but Safe Places for Women, a new shelter in an undisclosed location south of Denver, that will open next month to provide immediate care and shelter to women pushed into performing sex acts so someone else can earn money.

“This home is the first step for a survivor after she exits trafficking,” said Higgs, founder and executive director of the HER Campaign, whose mission is to help sex trafficking survivors “heal, grow, and find purpose … through providing residential programs.” Higgs ran a similar program in Billings, Montana, and, because of the need in Colorado, decided to expand south after a rigorous accreditation process.

The program is intended to meet the immediate needs of someone who has recently escaped sex trafficking. “We do have some medical [care], and then we also incorporate functional medicine to help them stabilize mind, body, and soul so that they can make an informed decision about what they want to do for their long-term future,” Higgs said during a recent interview onsite.

Sex trafficking is a growing problem in Colorado, with 84 reported cases in 2023. That makes Colorado the state with the 10th most cases.

The opening of the emergency shelter, which will survive on donations, is one of several ways sex trafficking is being addressed in Colorado. Other efforts are coming from a 10-year-old sex trafficking council that recently made training for law enforcement mandatory.

Sex trafficking is a crime with a very specific definition distinguishing it from prostitution, according to Maria Trujillo, human trafficking program manager at the Colorado Department of Public Safety. While prostitution involves free will, sex trafficking does not.

“Sex trafficking of an adult involves force, fraud, or coercion of that individual into providing commercial sex acts,” she said.

Sex trafficking occurs in Colorado more often than in most states. In October 2024, Common Sense Institute Colorado, a nonprofit think tank focused on Colorado’s economy, published a nine-page report using data from the Colorado Bureau of Investigation and the FBI.

Its findings show:

- Colorado was 10th in the country for instances of reported sex trafficking in 2023, with 84 reported cases. States with higher numbers are Texas, with the most cases (528); Georgia; California; Nevada; Wisconsin; Minnesota; Arizona; Tennessee; and Indiana.

- Colorado ranked again in 10th place for human trafficking reports per 100,000 residents, which takes into account the population of the state. Colorado had 1.44 cases per 100,000 in 2023.

- Sex trafficking is increasing in Colorado: 84 cases in 2023 is the highest recorded number for the state, which is 28 times greater than the number of cases reported in 2014, which was 3. Before that, it was a rarely reported occurrence in the state: between 2008 and 2013, only three cases were reported. The 2023 number more than doubled from 2020, when there were 39 cases reported. In 2021, there were 77 cases, and in 2022 there were 62.

- Certain parts of Colorado have more instances of sex trafficking than others. The report states that “these offenses are concentrated in a handful of counties, in particular Adams County, El Paso County, and Denver County. In 2023, Adams, Boulder, and Denver counties were the locations of more than half the state’s human trafficking.”

DJ Summers, director of policy and research at the Common Sense Institute, said he couldn’t pinpoint the reason for the increase: “We are at a crossroads of two major intersections for highways. We are relatively adjacent to the southern border. Those two are frequently used as explanations for why we might have a lot of drug trade, and some of those are used for an explanation for why we have this level of human trafficking, but there really just is not one single explanation that law enforcement officials are able to point to.”

He said law enforcement’s awareness is another variable in the upswing in the data: “A lot of this is very difficult to track because law enforcement officials aren't yet universally aware of what might constitute a human trafficking charge, so there's a lot of play there between how much is human trafficking going up and how much is it simply being charged more than it used to be.”

Although the number of cases is increasing, experts say that it isn’t necessarily due to an increase in occurrence, but an increase in awareness.

“Human trafficking is kind of a growing crime area and that more people, more law enforcement officials and more prosecutors, judges are being made aware of it and expanding their prosecutions and arrests to include it than they used to,” Summers said. “And as that grows, there's always a little bit of murkiness with some of the data attached to it.”

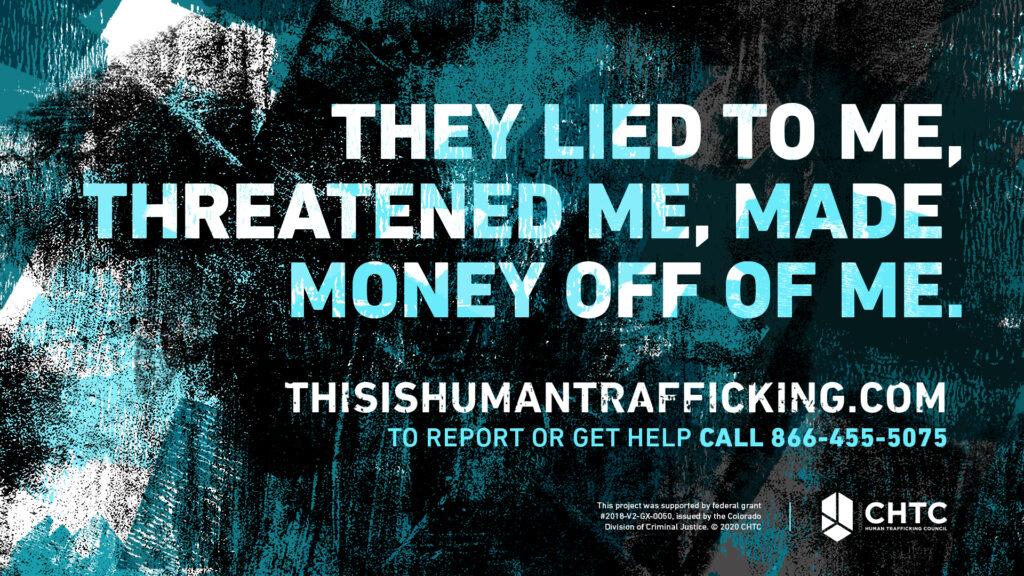

According to Trujillo, the state began a public awareness campaign on sex trafficking in 2020. The campaign was launched in part to “allow survivors to see themselves as a potential victim of human trafficking, and recognize that and maybe reach out for help and recognize that there is help to be given,” she said.

“As we’re able to push out the message more, we definitely see a direct correlation with that to more calls to the hotline and also more calls from survivors themselves,” Trujillo said.

The hotline, operated by the nonprofit Laboratory to Combat Human Trafficking, has 50 active anti-trafficking volunteers who respond to calls and texts to Colorado’s 24/7 Human Trafficking Hotline, collectively answering 5,000 calls and texts since 2018, according to its website.

In addition to the hotline, the state of Colorado has several laws related to sex trafficking. “In 2016, we helped pass legislation that allowed for child sex trafficking to be a form of child abuse and neglect,” Trujillo said. In April of this year, Colorado passed a state law that “makes the statute of limitations for human trafficking of an adult or a minor for the purpose of involuntary servitude and human trafficking of an adult for sexual servitude 20 years.”

Another change: now, members of law enforcement must complete training. The Colorado Human Trafficking Council created an online training called “Human Trafficking Investigations: An Introductory Course” as part of a law passed during the 2014 legislative session.

The online course takes about two hours to complete and starts with a pre-test to gauge knowledge on the topic prior to training, as well as online coursework about human trafficking laws, dynamics, identification, and investigations, followed by a post-test at the end.

According to Trujillo, now every officer in the state must take it.

“Just recently, actually last month, it did become mandatory training for all police academies ... It’s part of the police academy curriculum,” she said.

The new law also established the council. It has about three dozen members that include employees of law enforcement, nonprofit victim services organizations, and academia. Its purpose is to “bring together leadership from community-based and statewide anti-trafficking efforts; build and enhance collaboration among communities and counties within the state; establish and improve comprehensive services for victims and survivors of human trafficking; assist in the successful prosecution of human traffickers; and help prevent human trafficking in Colorado,” according to its website.

Even with the hotline, new police training, the council and the law, there will still be people who are sex trafficked, and for them, the shelter could be an option. Higgs said when it opens in January, law enforcement officers will likely suggest that sex trafficking survivors go there; victims may also find out about it themselves and ask to participate. Although she hopes women will begin and end the eight-week program as a cohort, a survivor could join at any time.

The shelter is intended to be a short-term therapeutic crashpad to stabilize sex trafficking survivors. Once a survivor completes eight weeks in the home, she could go on to a long-term shelter for sex trafficking survivors located on the same grounds that provides the opportunity for longer-term healing and planning for the future, Higgs said.

Before coming to Colorado, Higgs ran a similar shelter in Billings, Montana, and on nearly a dozen cases, worked with Andrew Yedinak, supervisory agent of the Human Trafficking Unit for the Montana Department of Justice.

In an interview, he said some sex trafficking survivors reach out, but the harder cases involve trafficking victims who don’t believe law enforcement wants to help them. He said sex trafficking victims are diverse in terms of socio-economic status, but scenarios he’s seen before involve women who are homeless and addicted to drugs, who are then told by a sex trafficker that he can provide her with a place to live and hook her up with the drugs she needs, but she’ll have to do some things in return.

When those things involve sex work in exchange for some stability, the trafficked person, often vulnerable already to manipulation, will believe the trafficker when told that she’ll be the one arrested if she goes to the police to get help. Coercive tactics keep the person victimized and unwilling to disclose their situation to law enforcement.

Yedinak, 40, who has worked in law enforcement for two decades, said the goal is to support the survivors, not arrest them.

He said he noticed that the repeated trauma a sex trafficking survivor is likely to undergo by the time she reaches a shelter often means they cannot provide a narrative of what they have been through.

“The sex work that they’re being forced to do, these people are essentially being raped time after time, but then they’re also being sexually abused by their trafficker, and they’re also being physically abused by their trafficker, being beaten for not being willing ... And when those things happen, we suppress those memories, and so that’s where, when we’re asking them to bring those memories back out so that we can investigate them, it’s very troubling for an individual.”

What Yedinak said has worked is to focus on the trafficking victim as a whole individual, give them the space and time to heal, and then gather their story to work on building a case against their trafficker. Sometimes, that cannot happen until the woman has regained some equilibrium.

And that’s what Higgs is preparing to do. To offer the short-term shelter service, Higgs first got certified, a process that is handled by the Virginia-based organization, the Safe House Project.

“We work alongside organizations who are either looking to launch a residential care program or expand services to make sure that they are using evidence-based and promising practices, and really establishing strong programs that really can help break the cycle of victimization for victims of human trafficking,” said Safe House Project CEO Brittany Dunn.

Having certified about 100 sex trafficking shelters around the country already, the organization looks at things like the potential population served, the programming that would be offered, and the goals for the people who use it. Dunn said Higgs’ HER Campaign, co-led by Higgs’ husband Sammy Higgs, received certification at the end of 2023. The team had set up a similar sex trafficking shelter certified through the same organization for short-term treatment in Billings, Mont., which will also re-launch in January.

“And so we're really excited to see them take all of the things that they have been successful within Montana and bring that to the Denver market where the HER Campaign really has been successful is serving those who have a wide variety of needs,” Dunn said. “They've really worked to bridge the gap to serve those who might have severe mental health needs or that also might need additional considerations … not only responding to the trafficking needs of an individual but really to that whole person.”

A pre-certification site visit included “a lived experience expert” – a person who had experienced both sex trafficking and some time in a shelter. That’s done “to make sure that we have that really infrared lens that a survivor gets to make sure that everything that should be happening is happening in the best way possible on the property,” Dunn said.

The holistic approach the HER Campaign will use to run the shelter can be seen throughout – right down to the free-standing bathtubs and the modern, sleek furnishings. The kitchen has both a breakfast nook and a large dining area so that community can be built among survivors around cooking and sharing meals. Although most bedrooms accommodate two survivors, there’s also a room specifically for people who have mental health concerns that might make it difficult for them to share spaces, Higgs said.

Also on the team is a registered nurse who pivoted from working in the labor and delivery arena to caring for people who, because of how they had been living, are likely low on nutrients.

“The functional medicine piece that we offer here became of high interest to me when thinking of the human body as a whole,” said registered nurse McKenzie Gibson, who will serve as program director. “And stabilizing the physical body as well as the mental health and the spiritual perspective together. So we'll do in-home IV infusions, brain neurofeedback, have sauna and a cold plunge, and a high emphasis on medical physiological stabilization here."

She said the intake of a blast of nutrients through IV vitamins helps people heal both physically and mentally. “A lot of times the presenting mental instability is not actually from a mental health disorder, it's from nutrition deficit,” Gibson said. “So if we can expedite that healing by meeting their needs in their body with vitamin C, vitamin Bs, magnesium stabilization nutrients, then it expedites their mental health healing journey.”

She said just eating healthy at the onset will probably not be enough to make up for the junk food and lack of sleep people who have been sex trafficked have likely experienced.

“Because when your body is so deficient, you can't just, through eating good, healthy food, you're not going to be able to get the deficit that's already happening. So those IVs just expedite it, and it just helps get your body stabilized so then you can eat healthy and it's going to be beneficial.”

Higgs said the program in Billings, Mont. offered an approach that was successful.

“What we saw was their anxiety went down and their PTSD went down, and then they were able to actually start on their healing journey and do some of the talk therapy and deeper inner work. But without that, they're just such in a stage of fight or flight that it's really hard for you to start to heal internally.”

Yedinak said he’s seen the effectiveness of the approach of emergency stabilization – without it, the survivor is often in a state of emotional disruption that would prevent her from describing what she’d been through, let alone picking up and starting a new life independent of her trafficker.

“People are suffering from things like drug-induced hysteria or hysteria that comes from trauma,” he said. So if he were to ask someone at that point to share it, “their moments in time can be all over the place. So trying to figure out, are they actually talking about last week, or are we talking about some point a year ago? … So not having those key facts can be very difficult. So what we find is when we serve the person first and get them stable with their mental health, those details start coming back.”

He said he tries to build a rapport with survivors, gain their trust, and then help them into a shelter like the HER Campaign, often with the assistance of a victim services coordinator who builds a bridge between law enforcement officers and survivors.

Higgs, who is looking forward to providing the services with the team that will include both the nurse Gibson, a social worker and others, said the short-term shelter will be one of the components available in Colorado to care for women who have been trafficked.

In Montana, the short-term model has been effective. When asked in how many instances he’s been able to see the impact of short-term care on survivors, Yedinak said: “Every single one of them.”

After feeling they can begin to trust those other than their traffickers, victims tend to see they have other choices. “And so having these shelters … they have this care that is a totality of all of the different traumas that exist amongst trafficking.”

The idea is to then give them the opportunity to make other choices once they are not being traumatized every day.

“Here we try not to do super deep behavioral or talk therapy. It's more about stabilization,” Higgs said of what will occur in the 7,000-square-foot, three-story house. “The goal is to have them go through the eight weeks and to graduate that, and to step into their next decision, whatever that is.”