This story was produced as part of the Colorado Capitol News Alliance. It first appeared at kunc.org.

By Chas Sisk, KUNC

Fifteen years ago, the state crime lab in Connecticut was in disarray.

A high-profile, Yale University murder case had been postponed while lawyers awaited DNA and other evidence. A serial rapist had been allowed to roam because of testing delays, and more than 10,000 DNA samples taken from convicted offenders had not been recorded in a national database.

The situation was bad enough, the lab would lose its accreditation.

“Once we started digging down into why that happened, it was pretty clear there were all kinds of problems with the lab,” said Michael Lawlor, Connecticut’s former undersecretary for criminal justice policy and planning. “It was just not competent leadership, basically. ... Somebody had to step in there and figure it out, and fortunately, we were able to put together a team that could do that.”

Today, the Connecticut Forensic Science Lab produces results that leaders in Colorado dream of, especially when it comes to investigating sexual assaults. Leaders in Colorado are studying it as they try to move on from a testing scandal and consider ways to solve test result wait times that are often over a year long.

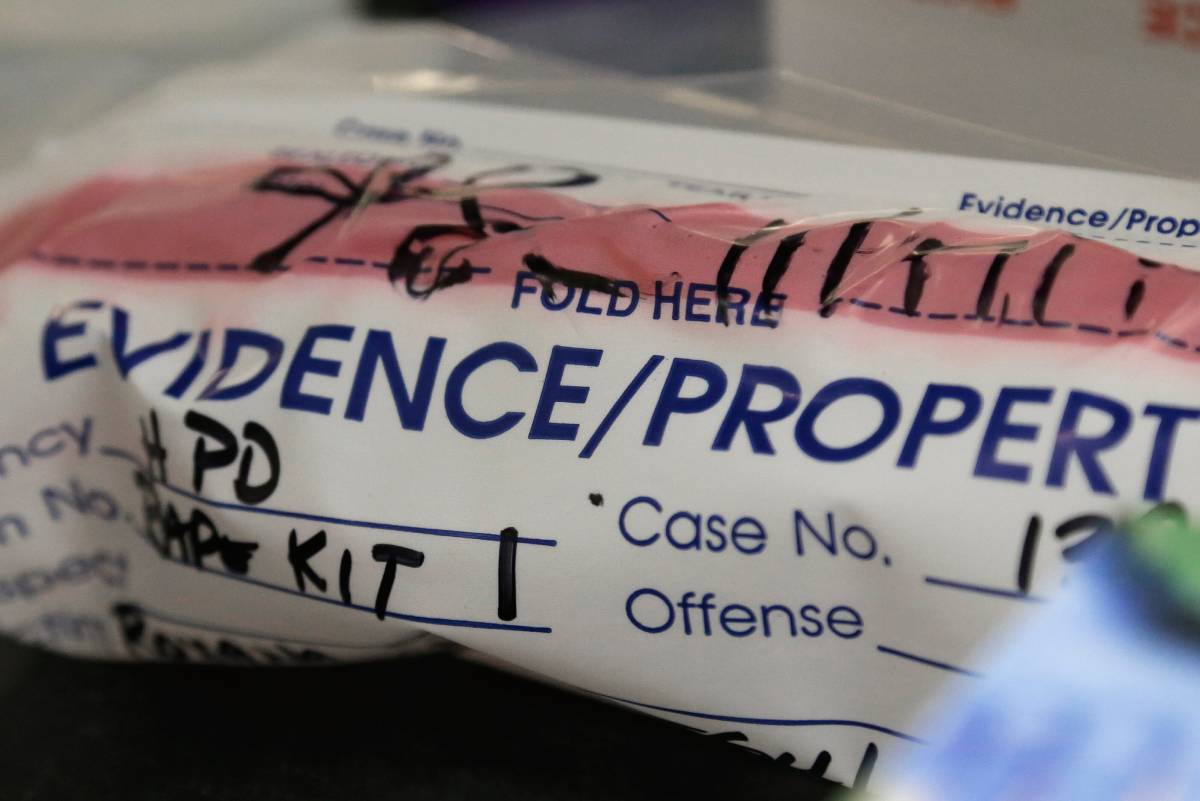

Sexual assault has been a focal point for labs nationwide since the revelation in the 2010s that tens of thousands of testing kits were moldering in police station vaults. Under Connecticut law, results from sexual assault kits must be returned within 60 days, but for the better part of a decade, its turnaround time has been 30 days or less.

Meanwhile, victims of sexual violence in Colorado routinely wait 18 months for results. That wait has delayed prosecutions and denied victims the closure and clarity that a forensic examination can provide.

“It, frankly, rips you up,” said state Sen. Mike Weissman, an Aurora Democrat who has sponsored several measures to address the testing backlog. “This offense wrecks lives. It splits souls.”

The wait in Colorado is unusually long, but the circumstances behind it are not unique. Experts say that crime labs all over the country are struggling with staggering workloads and a shortage of workers.

Shortages have led to setbacks in the decade-long effort to speed up testing of sexual assault kits. At the same time, officials in Colorado were learning of the backlog here, law enforcement in Oregon announced the wait time for results there had climbed to eight months.

And the wait for sexual assault kits may just be the most visible part of a deeper problem. To clear sexual assault kit backlogs, labs often delay or suspend testing in non-violent crimes.

Demand for DNA testing is also high in homicide investigations. The appetite from prosecutors and law enforcement to link suspects to homicides through forensics may lengthen investigations and produce longer waits for other results.

“We are asking too much of laboratories without providing resources to do what they are asking them to do at the level they're asking them to do it,” said Dr. Laura Gaydosh Combs, an associate professor of forensic science at the University of New Haven. “And so something has to give.”

$320 million spent on testing

The reemergence of sexual assault kit backlogs has caught public officials by surprise. They come 10 years after many states, including Colorado, took comprehensive inventories of the kits held by local police departments and sheriff’s offices.

Some of those cases dated back three decades or more, not long after evidence collection in sexual assault cases was first standardized. Whether because law enforcement was indifferent toward victims or the technology wasn’t advanced enough then to link samples to suspects, those kits had been ignored and their discovery led to a nationwide push to get them tested – and to vows that every victim going forward would see results.

The U.S. Department of Justice supported those efforts with a series of grants. It launched the Sexual Assault Kit Initiative, which since 2015 has sent $320 million to state and local labs. That has resulted in more than 100,000 tests and more than 1,500 convictions.

Many states also passed new laws establishing mandatory turnaround times for sexual assault kits and a requirement that all kits be tested, unless the victim asks otherwise. Experts say that has not been matched by increases in staffing or funding for labs.

“It's actually created this huge problem,” said Jennifer Doleac, executive vice president of the criminal justice program at the nonprofit Arnold Ventures, “because they don't have any more resources than they did before.”

The Colorado Bureau of Investigation says its backlog was caused by a combination of factors. One is short staffing, caused by a wave of state crime lab employees taking leave or other jobs.

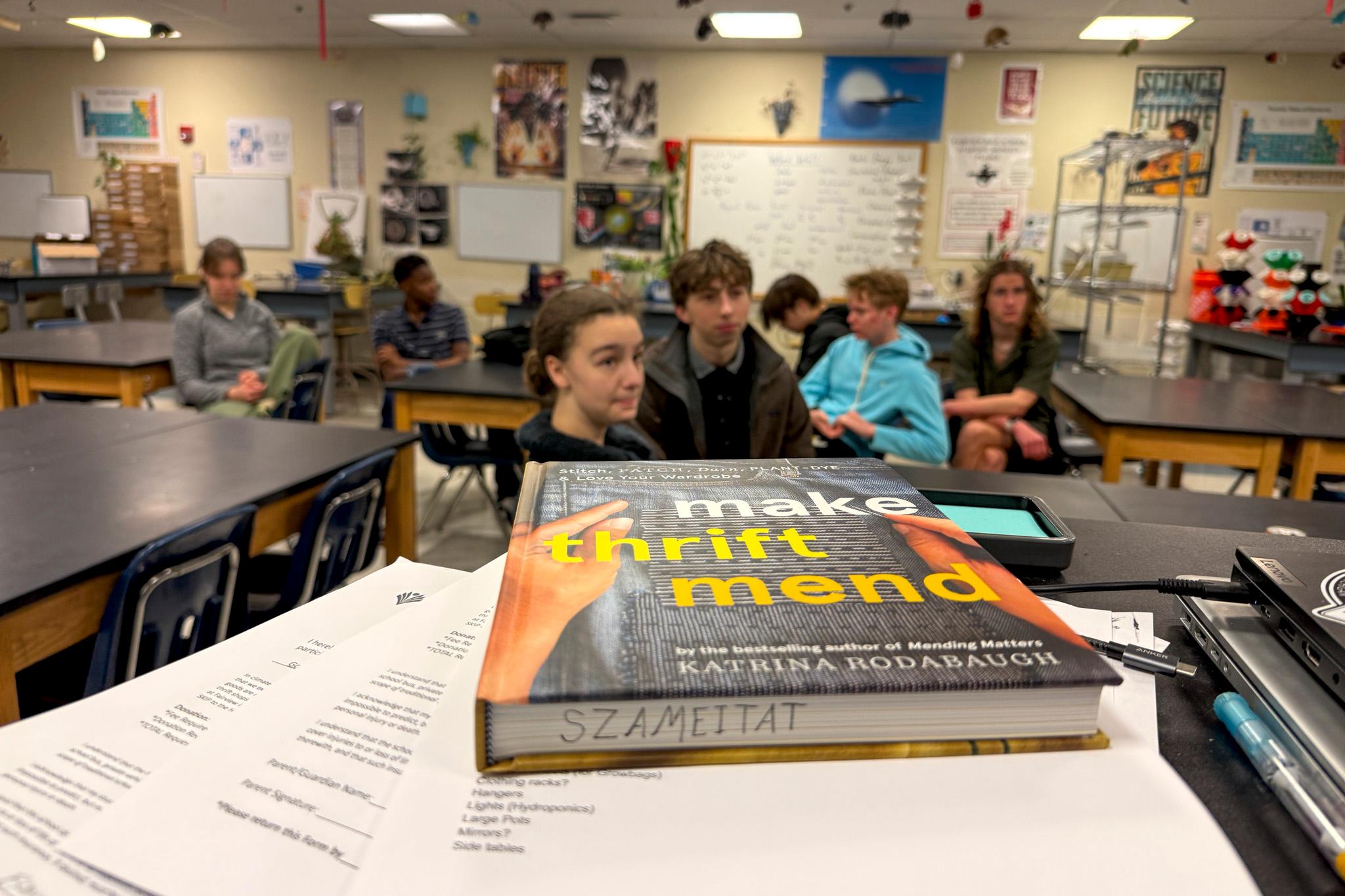

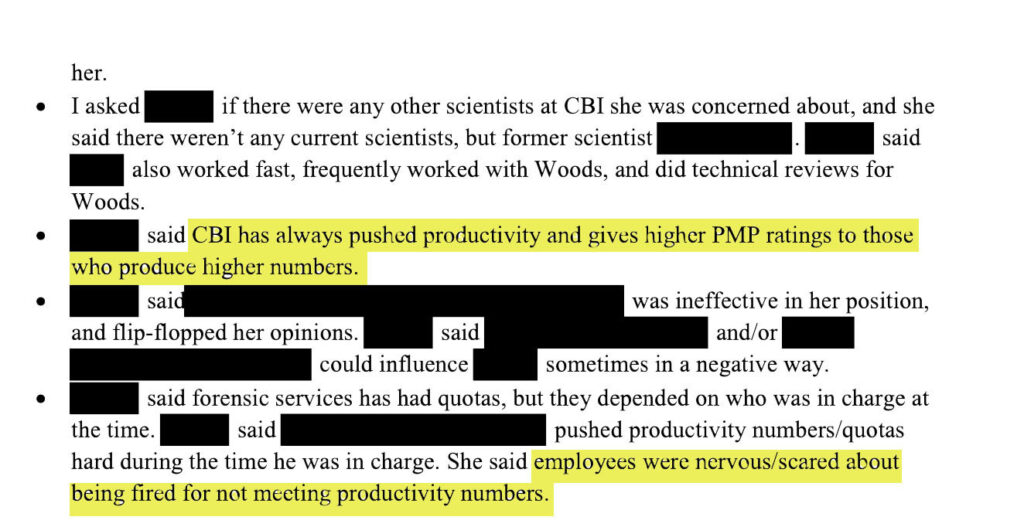

Compounding those shortages are the allegations that one veteran scientist, Yvonne “Missy” Woods, manipulated forensic tests for at least a decade. The claim forced the CBI to divert resources into reviewing more than 1,000 cases she was involved in.

The Woods case illustrates the pressure on crime labs. Over her 29-year career, Woods won accolades for being a top performer. According to an internal affairs report, investigators were told she returned twice as many results as the next fastest scientist.

There were suspicions she achieved those results by cutting corners, and there were quality control reports that flagged abnormalities in her work. But supervisors did not follow up, or they accepted Woods’ explanation that the flaws in her data were mistakes caused by stress and long hours.

When a full-scale investigation was eventually launched, Woods abruptly quit. She is now awaiting trial on 102 charges, including cybercrime, perjury, forgery and attempting to influence a public servant.

‘Predatory’ workloads

CBI officials have declined to comment on the Woods’ investigation directly, citing the pending charges. They have said that they have brought in a third party to review the lab’s practices and recommend organizational improvements.

Combs, who worked at crime labs across the country for 20 years before going into academia, has been following the Woods investigation. She also declined to comment on it directly, but said many forensic scientists experience intense pressure to deliver results quickly.

“It's predatory in some sense,” she said. “The personality type that goes into forensic science are the helpers. They are the people who are trying to do the most good. But it's also how you burn people out. It's also how mistakes get made. It's also how people can look for ways to cut corners.”

The demands come from all sides. For years, people in criminal justice have talked about the “CSI effect,” the expectation among jurors that cases will be backed with the neat, ironclad DNA results found on primetime crime dramas.

Their faith is not entirely unfounded. In recent years, DNA technology has leaped forward. It’s now possible to identify a suspect from “trace” DNA left when a suspect touches an object or a victim’s skin. In earlier days of DNA testing, forensic scientists had to find a body fluid, like spit, sweat or semen.

But as police officers and prosecutors have become aware of how powerful the technology has become, they have started to ask for more tests. Labs are often expected to sort through piles of evidence in the hope of finding the speck that will identify a suspect.

That work can take days or weeks. And the skills needed to do it are hard to come by. It takes a crime lab two years to fully train up a new scientist, after which they can often find better pay in the private sector.

“Across the nation, there is a capacity issue,” Lance Allen, the CBI deputy director who oversees the lab, told lawmakers at an April hearing. “In the last several years, the legislature has been very helpful to CBI, and we've received a lot of additional funding. And we are grateful for that, because it is going to get us on that path to being in a much better spot. But it is also a long-term investment.”

Combs said labs nationwide are watching how Colorado responds to the crisis.

“I don’t envy anyone taking a leadership role in laboratories,” she said. “They have an impossible mandate and an impossible task with just insufficient resources.”

During this year’s session, state lawmakers redirected $3 million to support the CBI lab, at least some of which will be spent on outsourcing tests. Local labs have also begun to handle sexual assault tests themselves, a move meant to ease the burden on the state lab.

A pending state law will require lab staff to report suspicions of misconduct and for there to be a state investigation when they do. Lawmakers also voted to create an oversight board that will report to the state legislature.

Meanwhile, the CBI is looking to bounce back from the decline in staff. It currently has 16 forensic scientists, a number it hopes to bring back to 31 over the next two years.

If all goes to plan, the CBI says it can bring turnaround times for sexual assault kits down from a current estimate of 554 days to 88 days. But it will take until March 2027 for it to reach that goal.

Lessons from Connecticut

The scrutiny being placed on the CBI’s crime lab is similar to the situation in Connecticut in the early 2010s.

Lawlor, who also now teaches at the University of New Haven, had a front-row seat to that lab’s struggles. A one-time prosecutor, he served in the Connecticut legislature for 24 years, rising to the chairmanship of the House Judiciary Committee.

Lawlor left the legislature to join the administration of Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy, who came into office in 2011 and made criminal justice a focus of his administration. Turning the Connecticut crime lab around was part of a larger overhaul of state law enforcement that included placing it under the leadership of a trained scientist.

“And I think if you spoke to prosecutors and law enforcement officials in Connecticut, I think they'd say that they're very satisfied with the way the crime lab runs today,” said Lawlor.

“That required a lot of funding, a lot of resources, and Gov. Malloy said, ‘You know, whatever it takes. We have to make sure that they can turn around all types of evidence, not just rape kits.’ ... And maybe that's the secret for other states.”

Connecticut has been proactive seeking federal grants for sexual assault kit testing. It has received five so far, totalling just less than $8 million.

The state also poured money into the lab. It now employs about 40 scientists and has an annual budget of more than $13 million.

But money alone does not explain its success, said Beth Hamilton, executive director of the Connecticut Alliance to End Domestic Violence. She said the state regularly updates its procedures, and the lab is also well-organized, with a team that reviews sexual assault kits as they come and figures out what evidence is most likely to yield results.

“Wonderful to pass legislation that says, ‘OK, we have to test these kits,’” she said. “But kind of the infrastructure around it also needs to be improved and keep up.”

Connecticut continues to invest in its lab. Over the next three years, it has allocated $2.5 million specifically for lab equipment, software and supplies. That spending in part replaces federal funding that will expire.

By comparison, Colorado will spend more than that, just to catch up on its backlog.

The one place Hamilton would like to see Connecticut do better is outside the lab – with more prosecutions.

“The point of folks going through evidence collection, the point of doing all of this, is in the hopes that there's some accountability on the other end,” she said. “And we have not seen that in Connecticut, right?”

Colorado looks ahead

Connecticut is, nonetheless, one of the states that Colorado has studied most closely as it moves forward.

Over the course of this year’s session, legislators increasingly moved away from describing the reemergence of the backlog as a tragic turn of events to one caused by management issues. And they pressed CBI officials on what it would take for its crime lab to match Connecticut’s results.

Late in the session, the agency came back with an estimate, based explicitly on the Connecticut lab’s staffing and funding practices. Authorities said Colorado could meet a statutory mandate to deliver all sexual assault test results within 60 days if its budget were increased by $3 million a year and the lab were allowed to add 20 more positions, including 17 more scientists.

That increase would put Colorado’s staffing on par with Connecticut, adjusting for the differences in the sizes of the two states’ caseloads.

On one of the final days of this year’s legislative session, Weissman issued a plea to lawmakers to make that allocation a priority in 2026 and to continue working on improvements at the lab.

“There is nobody in charge of Colorado forensic labs other than us,” he said. “If we really set our minds to it, my God, we can find $3 million somewhere, because I think we owe survivors of sex assault a whole lot better than they've been getting in Colorado.”

But, he says, doing better will require a deeper commitment than the state has made so far.

This story was produced by the Capitol News Alliance, a collaboration between KUNC News, Colorado Public Radio, Rocky Mountain PBS, and The Colorado Sun, and shared with Rocky Mountain Community Radio and other news organizations across the state. Funding for the Alliance is provided in part by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.