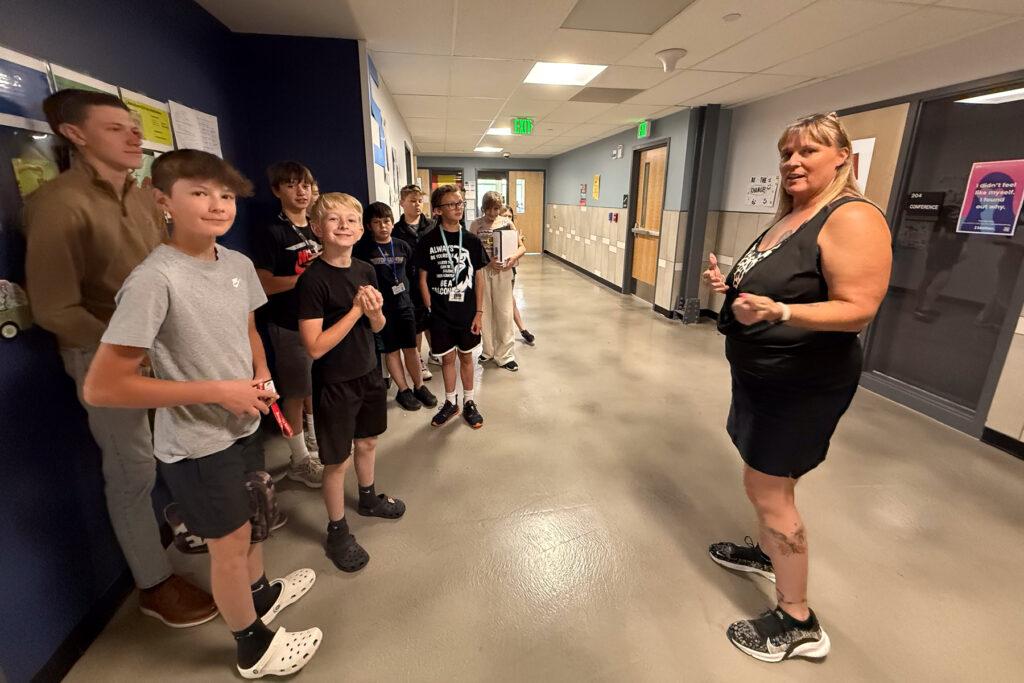

Shhhh. We’re in an eighth-grade classroom at Cañon Middle School and kids are working on compound and independent and dependent clauses.

Jolene Phillips circulates the room, making sure the students on her roster with special education plans are on task and getting the help they need. She spies a student drawing a bunch of purple triangles and gently whispers, “Why don’t we put these away?”

The student pushes back and says it's for extra credit. She redirects the student back to the lesson. Phillips describes her strength as building good relationships with students, but also being what she calls a “warm demander.”

“You are very firm in what you’re telling them, but you’re coming from a caring, loving place and they know that.”

State struggles with special education teacher shortage

Special education teachers such as Phillips are like gold. Rare and hard to find, especially in rural areas. This school year, Colorado began with a shortage of nearly 500 special educators. Over the course of the year, some of those positions were filled by long-term substitutes or retired teachers. At the end of the year, more than 100 were still unfilled.

“Colorado’s persistent shortage of special education teachers has put real pressure on districts,” said Margarita Tovar, chief talent and human resource officer for the Colorado Department of Education.

But shortages this year weren’t as bad as the previous two years.

One promising way to build the ranks of special educators is to help paraprofessionals, or classroom aides in special education, to become licensed teachers. Jolene Phillips fit the bill: two decades in the classroom as a paraprofessional under her belt. But how to get licensed? Going back to college would be expensive. Her journey into her own classroom took state support, an encouraging school and swinging a deal with her mentor.

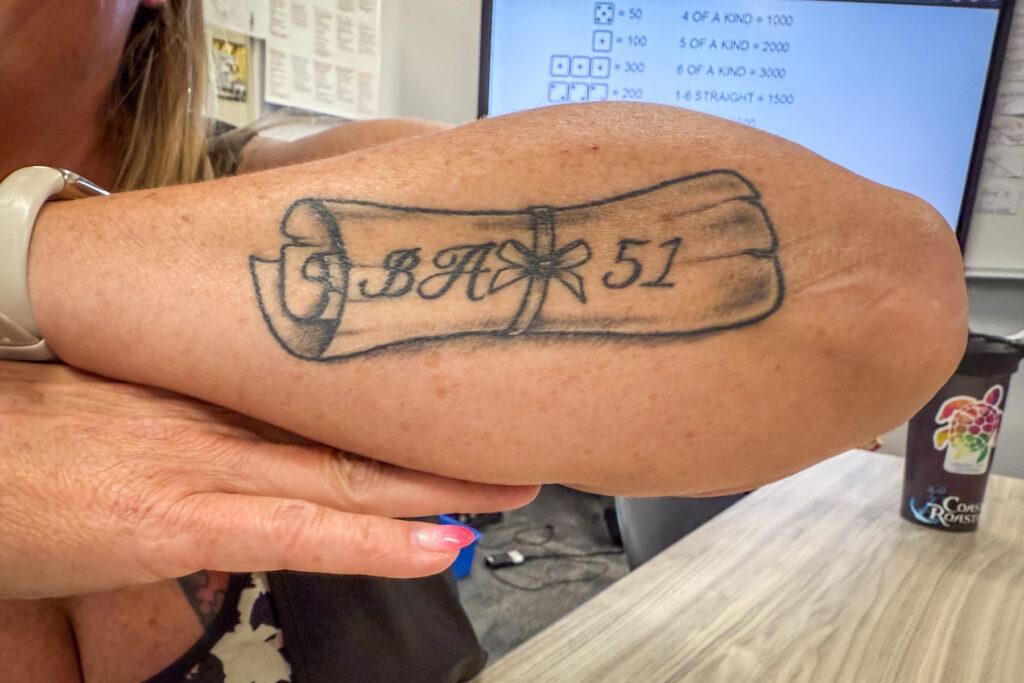

Now, Phillips is filling a desperately needed role in the small city southwest of Colorado Springs. And she has a new tattoo to prove it.

One key piece was the Educator Recruitment and Retention Program. It gave her a $10,000 stipend toward her educator prep program costs. Recipients must agree to stay in a teacher shortage area for three years as part of a program the state hopes will help fill teacher gaps.

“The Educator Recruitment and Retention program is helping turn the tide by giving teachers a meaningful incentive to stay,” said Tovar. “We’re starting to see progress.”

Phillips calls it a blessing.

“It was definitely a worry off of my plate so that my focus could be on not only my job, but then when I left and went home to do my job of being a good student,” she said.

A legislative report on the teacher recruitment program shows almost 70 percent of respondents considered dropping out of delaying their education preparation program before receiving financial assistance. A quarter of the recipients in the 2023-24 school year were special education candidates. There’s a need. In the most recent application, 942 people applied and 662 were selected.

“She was always there for me”

Phillips starts her days doing reading intervention with a small group of four sixth-graders at a table, along with many other noisy classmates.

They’re working on word definitions and other games based on a novel they’ve just read, “The Giver.” She helps them sound out words like chastise.

She’s positive and patient.

“I can’t focus,” said one student, as the volume in the classroom rises. It is the end of the year. So the group moves to a small room. It helps a lot.

Students like sixth-grader Danika, who tells me she grew 79 points on her end-of-the-year math test, are enthusiastic about Phillips' support.

“She helps me stay on task, and she is not mean about if I get words wrong – she just helps me with missing work. I just need a little bit of extra help and she helps me with it.”

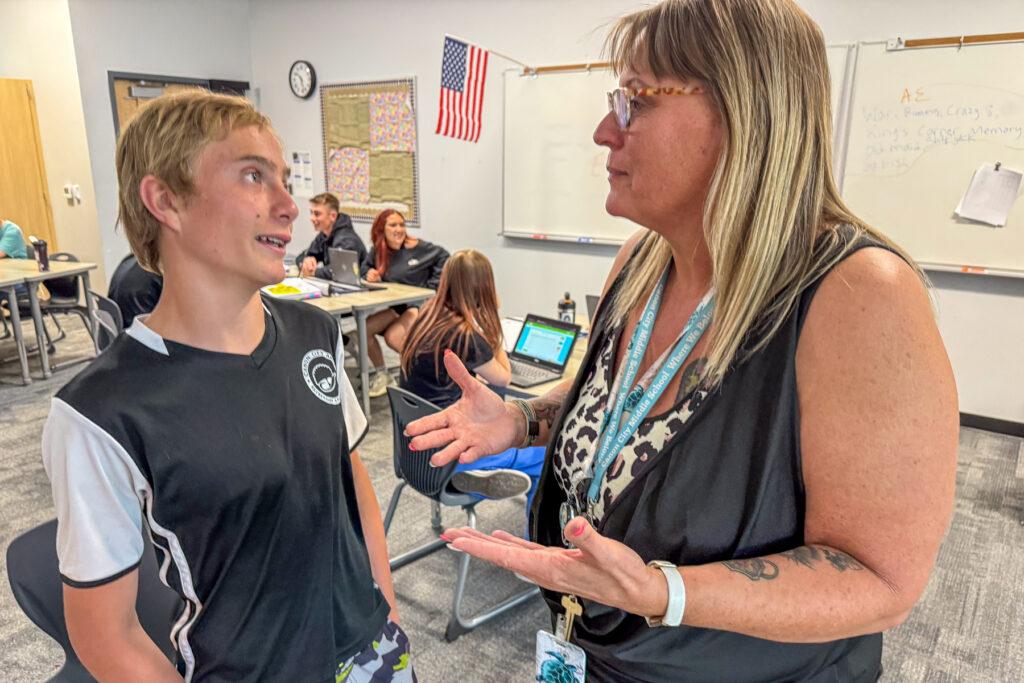

Phillips’ mentor is Dana Kalipolites, the school’s veteran special education teacher. Kalipolites said she’s seen really intelligent educators come out of teacher prep programs, yet they never can make that connection to students like Phillips can.

“She has a bubbly energy about her and kids just love her. She’s always encouraging them, laughs with them, and yet she will take on and own her own mistakes in the classroom, too. And the kids understand you can make mistakes, but you can learn from them.”

After the sixth graders, Phillips goes upstairs to eighth-grade English. She approaches a student, Devin, and asks if he handed in his missing assignments that they talked about. He shows her his grades. Some “A’s” and “D’s.” They high-five. That means he’s passing all his subjects and won’t have to pay for summer school. But Phillips keeps pressing, reminding him he has a science test today.

“Do you have notes for it? Were you paying attention in class yesterday?”

“Yeah.”

“So, you're gonna rock it? OK, I'm holding you to it.”

There are many students Phillips has kept from failing, like Devin, who said Phillips helped him “to read faster and better than I ever have.”

Another student, Duane, struggled with outside influences in sixth grade. Phillips forged a connection.

“He knows that I’ve got his back and that I care about him,” she said.

Duane is now moving on to high school.

“She was always there for me and she always wanted me to stay out of trouble,” he said.

Phillips holds her special education students’ feet to the fire. For example, they may want to get out of doing a presentation in front of their general education class. She’ll let them choose where they want to sit and will take half the class somewhere else, “but you're not getting away with not doing it because you can't do that in real life … You can't just quit a job because you don't want to talk to somebody. How can you pay your bills?”

As the English class winds down, Phillips confers with the classroom teacher about the test tomorrow so a substitute teacher will be comfortable administering the test to her special education students.

Her next class, she’s visibly excited for: academic enrichment that takes place in her own colorful classroom. The room is packed with plants, packs of cards, dice to play math games, art, topped off with an emotional support turtle named Michelangelo and smells pleasantly like eucalyptus and mint from an air freshener.

They’re playing a dice game, “Farkle,” today to practice math and communication skills.

“We talk about how to be good losers, right?” she tells the class. “And not get angry with each other. So be competitive, but understand that you're not always gonna win.”

The double deal that turned Phillips into a licensed teacher

Though Phillips has been in the classroom for 22 years as a classroom aide or paraprofessional, she’s been a licensed teacher for just a year. Then she was classified as a long-term substitute, working under Kalipolites and her special education case manager’s license.

Kalipolites, after 35 years in the classroom, wanted to retire. But she wanted to leave knowing Cañon Middle School was in good hands. The school had a deal for Phillips. Return to college for her bachelor’s degree while she worked full-time to become licensed. Phillips had a counter-deal for Kalipolites.

“I said, ‘The only way I'll do it is if you stay one year after I get my license.’ ”

Phillips wanted to make sure she was crossing her “i’s” and dotting her “t’s” under Kalipolites’ tutelage. There’s a lot of paperwork special educators must fill out legally and with precision.

But there were barriers to returning to college.

“I was trying to figure out all of the ins and outs, money-wise … how was I going to pay for that?”

Phillips also needed a fully online program. She discovered Western Colorado University’s program to help those who already had some college credits. They told her about several grants and the $10,000 Educator Recruitment and Retention program.

Once she began classes, Phillips could relate what she was learning – the terminology, the why behind the paperwork – to individual students she’d worked with.

“Everything just clicked.”

The program also provided mentors with deep special education experience who came and observed and provided feedback.

Phillips pulls up her sleeve to show a special tattoo, “B.A. 51.” She graduated at age 51 last May, the same year as her youngest daughter graduated from high school.

“It doesn't matter your age, it doesn't matter what you feel your limitations are. Be bigger, be better, blow those limitations out of the water.”

But next year could be rough. Kalipolites is retiring and will be tough to replace. The small district bordering the mountains west of Pueblo is currently hiring for four special education positions. For now, Phillips is touting the successes of the past three years, like Isaac in eighth grade.

Isaac’s big jump: “That’s what makes it worth it.”

When he arrived at Cañon Middle School from fifth grade, he said he could not read, write or do math.

“I was not the best at very much anything,” he said.

But with intensive help from a special ed program, he began improving. This year, though, when he took his end-of-the-year reading test, he bombed it. But Phillips knows when “there’s more gas in the tank and you’ve got more to give.”

“Why did we make you redo it?” Phillips asks Isaac.

“‘Cause I did really bad,” said Isaac.

“But why did we make you redo it?” she repeats.

“’Cause you believe in me.”

Phillips put Isaac in a room by himself to do the test again. She’s found that is the only way some students can concentrate.

When she saw Isaac’s score had jumped nearly 100 points, she had tears in her eyes. In one year, he went from reading at the beginning of the fourth-grade level to the beginning of the eighth-grade.

“That’s big, and that’s when you know you changed that kid’s life forever, because now he can go take his driver’s test, he can go get a job … that’s what makes it worth it.

Phillips said she’s keeping Isaac’s test forever.

Funding for public media is at stake. Stand up and support what you value today.