Livine is blunt in her description of her relationship to her phone.

“Parasitical.” The 15-year-old said it profits off her and she gets harmed.

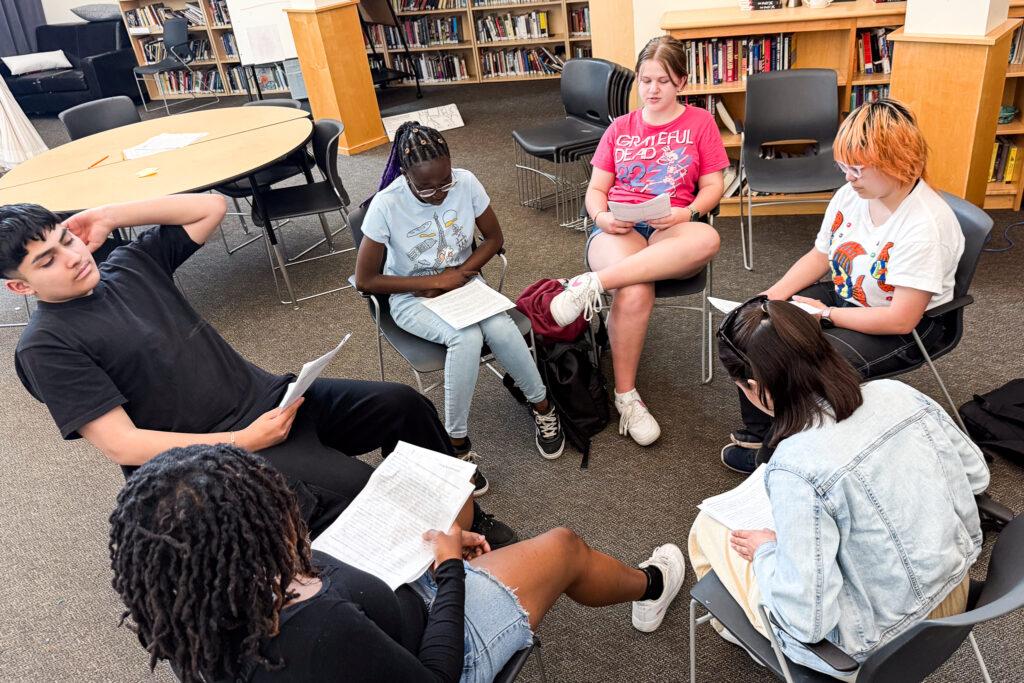

“Sometimes when I'm using my phone, and I try to put it down, I just feel like I want to use it even more,” she tells four other freshmen gathered in a circle in a school library. The teens each hold notes. There is no teacher.

It’s a Socratic Seminar — student-led and question-based, á la Socrates, the ancient Greek philosopher — and it’s just one tool on the road to recovery from an addiction to a powerful device that’s got billions of people in its grip: the cell phone.

Frustrated parents know all too well battling their teens over phone use. But what about when teens themselves do a deep dive into how the addictive devices hijack their brains? Would it change their habits? We checked in with a group of freshmen at Aurora’s William Smith High School who’ve taken a three-part course on the matter. The issue is relevant given a recent law passed by the Colorado legislation requiring school districts to develop a policy on phone use.

Students begin with a neuroscience project to understand how neurotransmitters like dopamine, linked to pleasure, are released in the brain with every “like,” notification and comment on the phone. They learn how phones activate the brain’s reward center, creating a “dopamine loop” that sucks you into staying on your phone for longer. Next, the teens tracked their phone use for four weeks and journaled about it. Finally, they learned how to develop their own “wellness playbooks,” healthier strategies to pass the time and deal with anxieties.

“They're not supporting your autonomy or your well-being.”

Back in the circle for the Socratic Seminar, the students state claims and evidence and question each other to spur deep conversation. Piper, also 15, quotes a line from the documentary “The Social Dilemma,” where she learned how the phone is designed to be addictive.

“I know that my phone is designed to trap my brain and keep scrolling on it. When we first started the class I was super surprised with my screen time … how is it that much? It doesn't feel like I'm on my phone that much and now I know that it's actually designed to keep me scrolling on it as long as I can so that they can make money.”

“This week I tried to put my phone away when I got home. For as much as I tried I always found myself picking it up again and again.”

It’s even more nefarious than that, Daniel, 14, adds. He quotes a line from the film.

“Everything they're doing online is being watched, is being tracked, is being measured. Every action you take is being carefully monitored and recorded.”

The teens seem a little freaked out by this knowledge — the relentless notifications unleashed by a billion-dollar industry that’s designed to keep them on their phone. But their teachers believe if they can reflect with each other on it, and analyze and discuss their own use together, there’s a fighting chance they can become more responsible users.

Teacher Ryan Clapp said you can’t blame a 15-year-old who has an undeveloped prefrontal cortex for being on their phone all the time.

“These are fiendishly addictive devices, and they're made that way by billion-dollar companies employing cutting-edge psychology and social science,” he said. “It's not a fair fight, and we don't want our students to have to fight this on their own.”

Clapp said for social media addiction to go the way of teen cigarette smoking, it needs to be a peer-led, peer-validated movement. A teacher can say “put away your phone away” a million times, but until students can reflect with each other on the costs of time wasted on phones, there won’t be meaningful change, he said.

For the Socratic Seminar, teacher Paul Grzybowski adds the teachers aren’t handing out questions and telling students to answer them.

“They're saying, what are your questions about this and what are some solutions for us?”

The consequences of moving social life online

The students take up the claim that the phone has manipulated and distorted the very meaning of culture and communication. They cite claims from The Atlantic magazine’s “The Terrible Costs of a Phone-Based Childhood” that social media has created a generation largely cut off from older generations, including knowledge about how to live a flourishing life. Frida, 16, feels that when she talks to her aunts, uncles, and grandma about when they grew up.

“I'm like, wow, life sounds so much more peaceful, so much more calm, you know, so much nicer because they didn't have phones,” she says. “You just learn so much from just talking to other people instead of always constantly being on your phone avoiding human connections.”

The teens ask each other questions about whether the phone causes them to compare themselves to others and how it makes them feel. Kai, 14, says those comparisons motivate her to do better but she said it wasn’t always that way. Frida says reading so much about all the achievements of others “overwhelms her.”

They talk about the opportunity cost of phones, how much of life, including contemplation and imagination, is exchanged for screen time.

It’s not like these teens don’t have hobbies. They do. Cooking. Digital art. Drawing. Crocheting. But they’re often bored without their phones. The phone entertains them – remember, it’s designed to do that. But they acknowledge how the phone has changed them socially by relying on them in situations when they’re uncomfortable and using them as a coping mechanism.

“If I'm at a party or something, I'll scroll on my phone if I'm bored or if I'm bored at home,” Piper explains. “I think that it's just like an easy solution for boredom to fill your mind with random things that you don't have to pay attention to.”

Eddie, who uses they/them pronouns and who is on the phone 10 to 12 hours a day, asks the group about whether using it as a coping mechanism is good or bad.

“For some people, they can’t find people in real life so sometimes they find people online to help,” Eddie says.

“I think that’s a much different thing than becoming addicted to your phone,” Piper responds sympathetically. “I think using it that way is good but if you start thinking negatively about yourself or you start acting different, negatively, then I think that’s when it becomes a problem.”

Kai says she hopes in that situation a parent would help guide that child through that isolation like making sure an online therapist is the right person. Frida reminds the group what they learned about when you are relying on dopamine hits from what you think are social connections with people.

“I feel that’s when things have gone south for you and need personal connections and not the phone,” she says.

Piper said that’s where parents might need to limit usage so that a child can’t use the phone as a coping mechanism. But the students agree phones are tough for parents to regulate. Some admit they hate it when their parents locked down their phones. They want parents to talk openly with their kids about phones and listen to the child’s concerns.

How to break the addiction

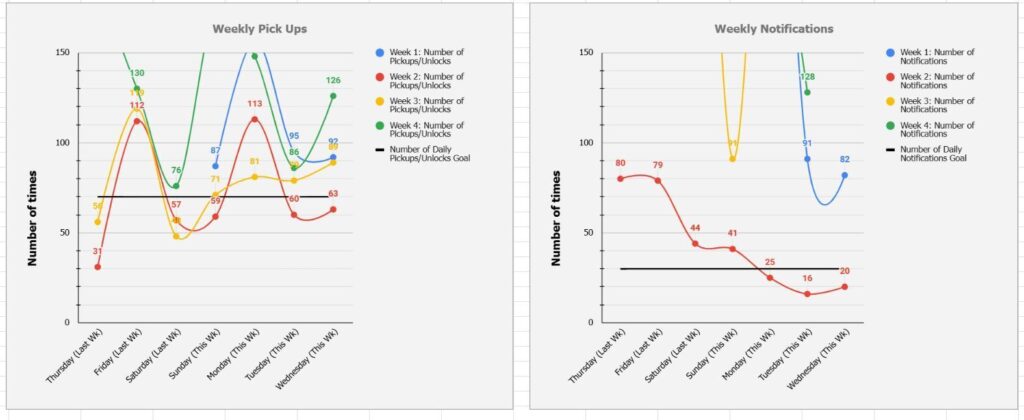

Perhaps the most powerful part of the course is a four-week “Screen Time Experiments” where students journal and track their daily minutes, notifications and “pickups,” how many times they look at their phone screen or hold it. They get to compare what they thought they spent on their device to reality and then their use goals.

“I would like to try grayscale on my phone for the upcoming week in the effort to try and get more sleep or at night.”

To see that evidence in black and white and transformed into a graph was alarming for them. Piper averaged six hours a day. She sometimes gets it to four now but still struggles. Before the course, Livine was at 8 hours a day and now it’s 3.5. Daniel is more cautious about the amount of time he spends on certain apps now. Many have deleted apps, “and actually my life has been so much better,” said Frida.

The teens practiced and analyzed strategies to put down the phone. Eddie struggled with keeping the phone outside of their bedroom.

“I was trying to go like a day without it and I couldn't even do that.”

Some found shutting off notifications actually made it worse.

“It causes you to be checking your phone every 30 seconds like who's texting me?” said Kai.

But others found turning off notifications significantly helped reduce the number of incoming notifications and phone ‘pick-ups.’ “Instead of being on my phone checking notifications, I was focused on the assignment and even forgot about my phone at times.”

Others tried “downtime” on a phone — allowing only certain calls or messages to come through — or turning the screen to grayscale, blocking the visual stimulus of color, those little red notification buttons. Frida found that strategy worked for her. She became more engaged in life.

“I don't know why but I felt better having my phone on grayscale because I used it much, much less and I did so much more and I just enjoyed talking to people. That's when I actually started enjoying doing the Socratic Seminars and going to class and doing all of (the teacher’s) community-building activities.”

Her use went from five to one or two hours a day.

“Instead of being on my phone checking notifications I was focused on the assignment and even forgot about my phone at times.”

Part of the course involved going to middle schools where the freshmen presented workshops on what they’ve learned to encourage younger students to do their own use experiments.

“Our students were like, ‘it’s too late for us,' but save the children!” said Clapp.

He believes collective action will help strike a better digital balance. Students reflecting on their own use data and accountability measures from supportive adults.

The hour concludes. I think Socrates would have been proud.